When the romantic leads of a drama are named after an idiom that originated thousands of years ago, it’s as though their bond was written in the stars.

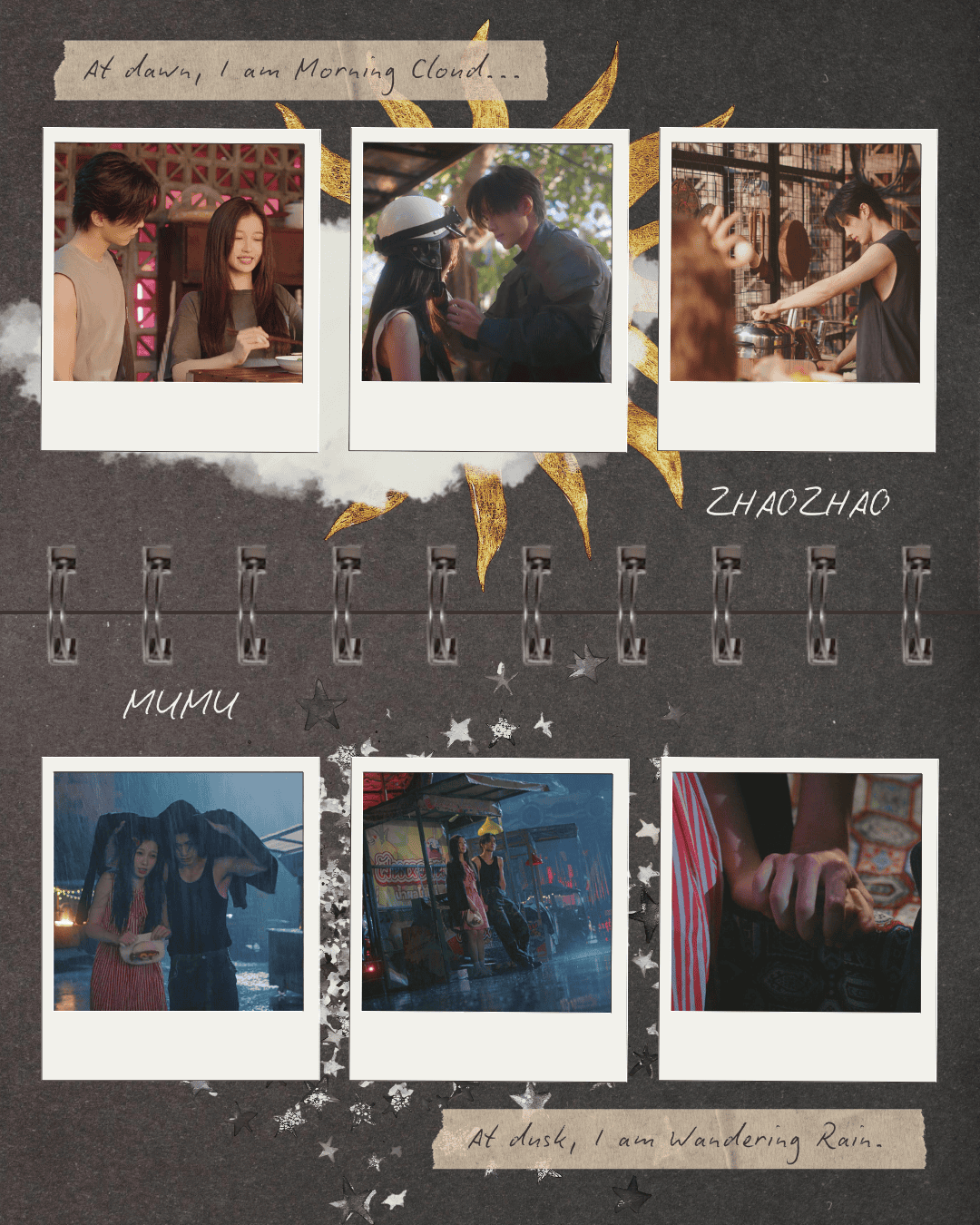

In ‘Speed and Love,’ starring Esther Yu as Jiang Mu and He Yu as Jin Zhao, the characters’ nicknames are Zhaozhao (朝朝 zhāozhāo) and Mumu (暮暮 mùmù). Joined together, they form the expression zhaozhao mumu (朝朝暮暮, zhāozhāo mùmù), which means “dawn after dawn, dusk after dusk.” Speak their names aloud, and the promise is there: to be together from dawn to dusk, day after day, never to be apart.

Their every longing gaze, every separation, every moment of devotion resonates with expressions of this exact human experience across the millennia. Theirs is a love story that finds home within a constellation of classical poetry, mythology, and imagery that has shaped how romantic devotion is understood in Chinese culture.

Whether or not the production team of ‘Speed and Love’ entirely succeeded in its execution, the cultural foundation underlying its central love story offers rich material for exploration.

Let’s follow these literary threads back to their origins.

Zhaozhao Mumu: Origins, Rhapsody, Desire

The idiom zhaozhao mumu finds its earliest literary expression in the Gaotang Fu (《高唐赋》Gāotáng fù), meaning ‘Rhapsody on Gaotang,’ composed by Song Yu during the Warring States period. The text presents a dream encounter between a king of Chu and a goddess known as the daughter of Mount Wu (‘Shaman’), who tells him:

At dawn, I am Morning Cloud;

At dusk, I am Wandering Rain.

Dawn after dawn, dusk after dusk, beneath the Terrace of Yang.

旦为朝云,暮为行雨。朝朝暮暮,阳台之下。

dàn wéi zhāoyún, mù wéi xíngyǔ.

zhāozhāo mùmù, yángtái zhī xià.

Because the king slept with the goddess in the dream, the imagery of “clouds and rain” in this piece became a euphemism for lovemaking in Chinese literature. The Gaotang Fu itself was foundational in establishing the literary conventions for depicting romantic goddesses and human-divine relationships as expressions of unattainable longing and the transience of time.

Originally, zhaozhao mumu described the literal passage of time — from dawn to dusk, every day, emphasizing continuity and repetition. But through many centuries of literary use, it accumulated deeper symbolic meaning: devotion, the faithful marking of time spent together or in constant longing.

By naming its protagonists Zhao and Mu, ‘Speed and Love’ promises a story about that kind of enduring devotion: “dawn after dawn, dusk after dusk, never to be apart” (“朝朝暮暮,永不分离。” zhāozhāo mùmù, yǒng bù fēn lí).

Tiffilosophy Picks:

An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911, edited and translated by Stephen Owen.

Cowherd and Weaver: Mythology, Poetry

‘Speed and Love’ echoes the mythology of Niulang and Zhinü, or ‘the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl’ — one of the most enduring love stories in Chinese culture.

Niulang, a mortal cowherd, falls in love with Zhinü, a celestial weaver and daughter of Xiwangmu, the Queen Mother of the West. Niulang, a mortal cowherd, falls in love with Zhinü, a celestial weaver and daughter of Xiwangmu, the Queen Mother of the West. She forbids their union. In one version of the legend, Xiwangmu draws a golden hairpin across the sky, creating the Celestial River — the vast Milky Way — to separate the lovers for eternity.

Zhinü gazes across the Celestial River at Niulang and weeps until her voice gives out. Niulang, too, cries in deep sorrow. Moved by the lovers’ unwavering devotion, the Queen Mother eventually permits them to reunite once a year, on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month. On this day, the Bird Deity orders magpies to gather and form a bridge across the Celestial River, enabling the lovers to cross and reach each other.

The myth may sound outdated to some, but it endures because it resonates with the reality of unavoidable separation and the faith that undying devotion can transcend distance.

‘Speed and Love’ mirrors elements of this myth in its exploration of Jin Zhao and Jiang Mu’s relationship. Like the mortal and the goddess, they are two people from seemingly incompatible worlds who face a disapproving maternal figure and forces that would keep them apart, yet they defy the odds through their devotion to each other.

The Song Dynasty poet Qin Guan connects the dots between the Niulang and Zhinü legend and the idiom zhaozhao mumu in his ci lyric poem ‘The Immortal at the Magpie Bridge’ (《鹊桥仙·纤云弄巧》 Quèqiáo xiān · Xiānyún nòngqiǎo). Here is the relevant section:

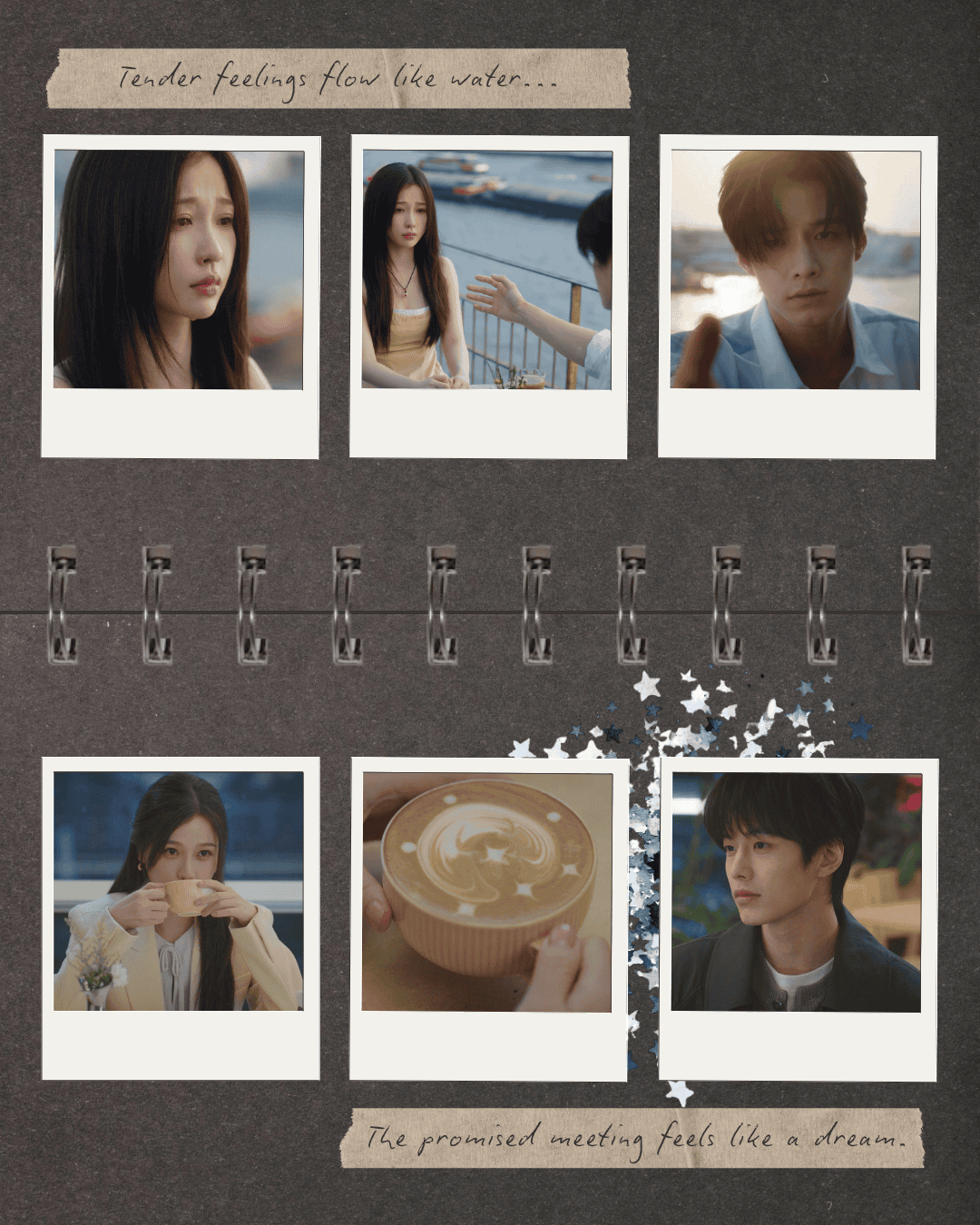

Tender feelings flow like water;

the promised meeting feels like a dream.

How can one bear to look back

at the road home from the Magpie Bridge?

If two hearts are meant to endure,

why should love depend on being together day and night?

柔情似水,佳期如梦,忍顾鹊桥归路。两情若是久长时,又岂在朝朝暮暮。

róu qíng sì shuǐ, jiāqī rú mèng, rěn gù quèqiáo guīlù. liǎng qíng ruò shì jiǔ cháng shí, yòu qǐ zài zhāozhāo mùmù.

The same message flows like water through the ages, from the legend of Niulang and Zhinü, to Qin Guan’s poem, and now to Jin Zhao and Jiang Mu: when love is sincere, even infrequent meetings are more meaningful than day-to-day proximity without true connection.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

The Cowherd & The Weaver Girl: A Qixi Festival Chinese-English Bilingual Picture Storybook for Families by Freda Chen.

Cowherd and Weaver Meeting Bookmark.

Yearning Day and Night: Idiom, Ming Story Collection

Jiang Mu finds Jin Zhao’s keychain inscribed with zhaosi muxiang (朝思暮想 zhāosī mùxiǎng), a Chinese idiom meaning “to yearn day and night,” which also contains their names, Zhao and Mu.

This idiom appears in Feng Menglong’s story collection Stories to Caution the World, compiled during the Ming dynasty:

Ever since Shen Hong caught sight of Yu Jie on the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival, he has been yearning for her day and night, to the point of neglecting sleep and forgetting to eat.

再说沈洪自从中秋夜见了玉姐,到如今朝思暮想,废寝忘餐。

zài shuō Shěn Hóng zì cóng zhōngqiū yè jiàn le Yù Jiě, dào rújīn zhāosī mùxiǎng, fèiqǐn wàngcān.

This moment of consuming desire — “neglecting sleep and forgetting to eat” — captures the physical toll of longing that zhaosi muxiang describes.

Feng Menglong compiled three influential story collections: Stories Old and New (Gǔjīn Xiǎoshuō), also known as ‘Stories to Enlighten the World’ (Yùshì Míngyán); Stories to Caution the World (《警世通言》Jǐngshì Tōngyán), which we have touched on here; and Stories to Awaken the World (《醒世恒言》Xǐngshì Héngyán). Together, they are collectively known as the ‘Three Words’ or Sanyan (《三言》Sān Yán).

Through his compilations of stories from diverse sources, including oral tales and earlier written accounts, and by presenting them in accessible vernacular prose, Feng Menglong elevated the status of popular literature and created an enduring archive that would influence generations of Ming and Qing writers. His work painted rich portraits of people's lives from all walks of life — merchants and scholars, courtesans and monks, matchmakers and thieves.

By inscribing zhaosi muxiang on his keychain, Jin Zhao joins the tradition of expressing devotion through personal, everyday objects. In traditional Chinese culture, jade pendants (玉佩 yùpèi) and scented sachets (香囊 xiāngnáng) are worn close to the body as intimate keepsakes, gifted to or exchanged between loved ones. These objects carry emotional weight precisely because they are touched daily, warmed by skin, and often require skill and time to create. The act of inscribing such tokens transforms ordinary items into vessels of memory and promise. To yearn morning and night, as zhaosi muxiang conveys, is to make remembering itself an act of fidelity.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Stories to Caution the World, compiled by Feng Menglong, translated by Shuhui Yang and Yunqin Yang.

The rest of Feng Menglong’s story collections:

Stories Old and New, compiled by Feng Menglong, translated by Shuhui Yang and Yunqin Yang.

Stories to Awaken the World, compiled by Feng Menglong, translated by Shuhui Yang and Yunqin Yang.

Red Beans and Bone-Deep Yearning: Tang Poetry

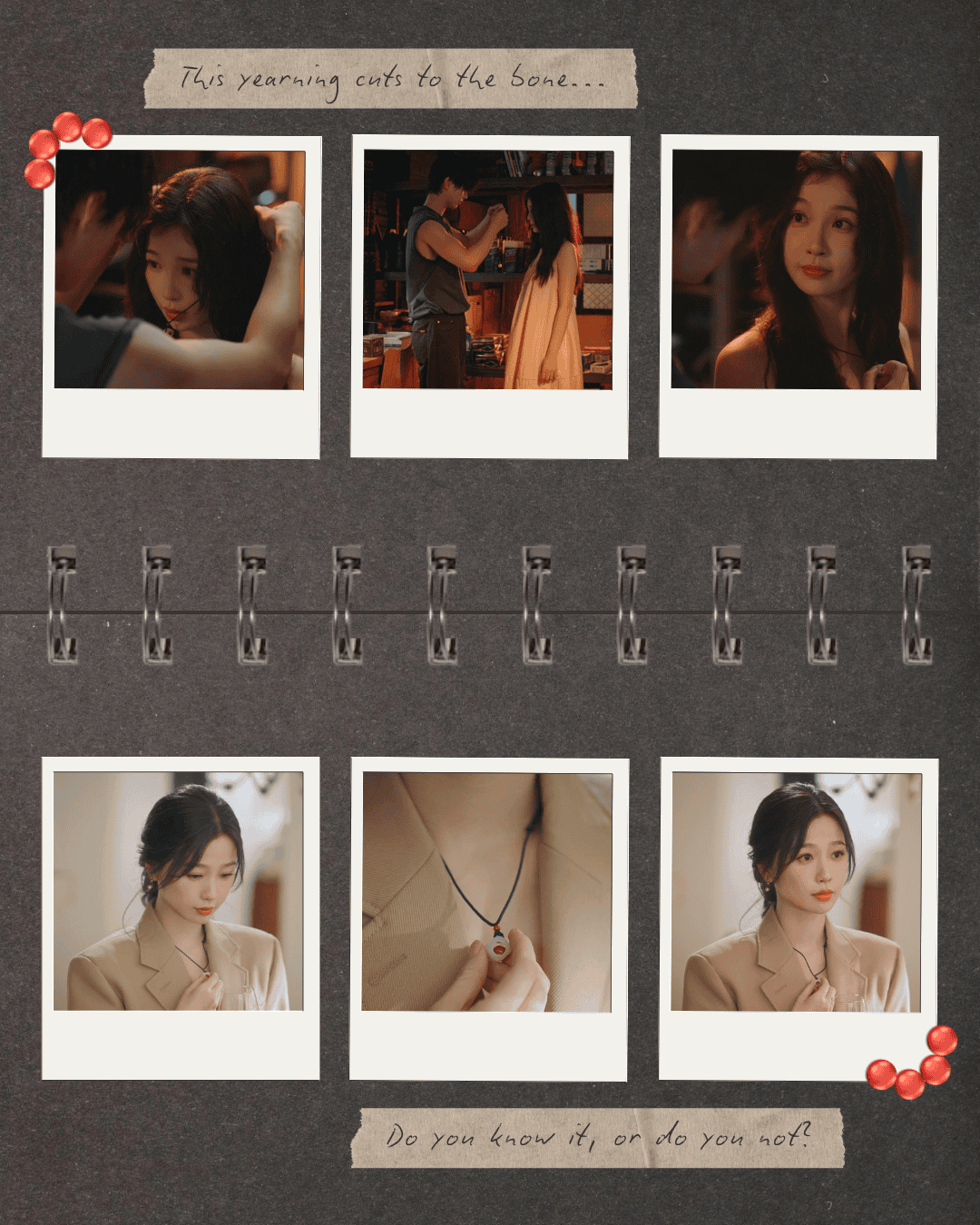

Beyond carrying a keychain that represents his intense yearning, Jin Zhao later gifts Jiang Mu a necklace steeped in classical symbolism: a red bead enclosed within a white stone cube. In doing so, he draws on the tradition of expressing love and affection through intimate tokens and alludes to one of the most iconic symbols of lovesickness in classical Chinese poetry — the red bean of yearning.

The red bean (红豆 hóngdòu) as a symbol of yearning was established by Tang Dynasty poet Wang Wei in his celebrated poem Xiangsi (《相思》Xiāngsī), which means ‘Yearning’:

Red beans grow in the southern lands;

When spring arrives, how many branches bloom?

May you gather them in abundance,

for this thing most embodies yearning.

红豆生南国,

春来发几枝?

愿君多采撷,

此物最相思。

hóngdòu shēng nán guó,

chūn lái fā jǐ zhī?

yuàn jūn duō cǎi xié,

cǐ wù zuì xiāngsī.

Wen Tingyun expanded on this symbol in his poetic work ‘Newly Added Lyrics to Willow Branches: Two Poems’ (《新添声杨柳枝词二首》Xīn Tiān Shēng Yángliǔzhī Cí Èr Shǒu). The second poem expresses a woman’s thoughts to her departing lover through wordplay that allows surface meaning to conceal deeper emotions.

While the poem’s final lines are the most famous and are directly quoted in the drama, it is the preceding line that reveals the full brilliance of its double entendre:

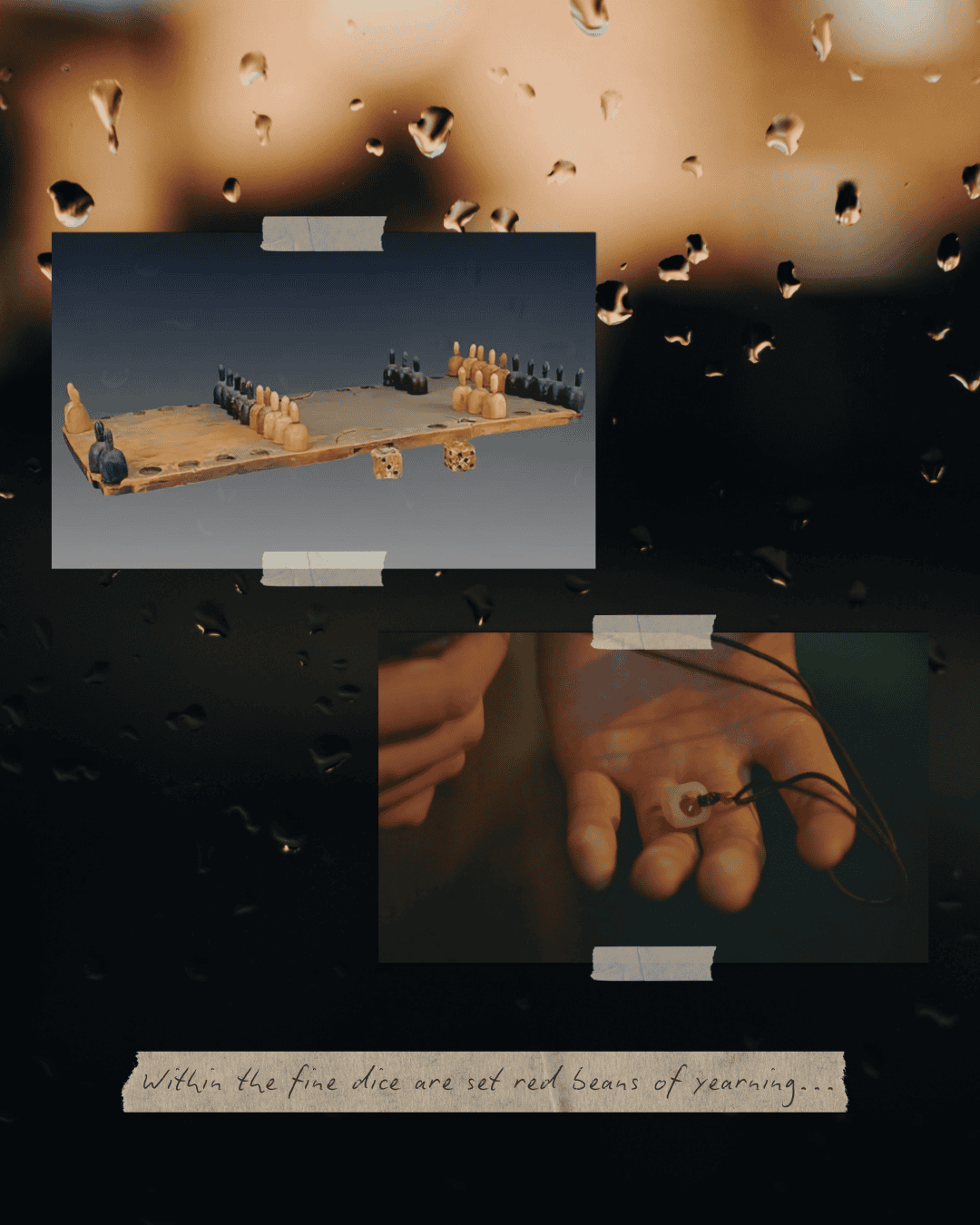

Don’t play weiqi, play changxing.

共郎长行莫围棋

gòng láng chángxíng mò wéiqí

On the surface, weiqi (围棋 wéiqí) refers to the Chinese strategy board game, internationally known as Go, while changxing (长行 chángxíng) is a dice-based gambling game popular in the Tang Dynasty. The poem’s narrator appears to be urging her lover to play changxing instead of weiqi.

But spoken aloud, there is a double meaning. Weiqi, the board game, sounds identical to 违期 (wéiqí), meaning ‘to miss an agreed time or break a promise.’ Meanwhile, changxing, the dice game, is written and pronounced identically to the term for ‘a long journey’ (长行 chángxíng). On this deeper level, the line means:

When embarking on a long journey,

Don’t miss the agreed time for return.

The narrator is actually saying: “When you travel far, do not delay your return.”

Now we can read the poem’s iconic final lines with this context:

Within the fine dice are set red beans of yearning,

this yearning cuts to the bone — do you know it, or do you not?

玲珑骰子安红豆,入骨相思知不知?

línglóng tóuzi ān hóngdòu, rùgǔ xiāngsī zhī bù zhī?

These lines connect directly to the dice game mentioned in the previous line’s surface reading. It appears to describe the red dots set into fine white dice, resembling red beans embedded in bone.

Knowing the narrator misses her lover and hopes for his swift return, we recognize she is likening her intense feelings to red beans of yearning that cut deep to her bones. A seemingly light suggestion to play a dice game carries hidden meaning: through the dice themselves, she reminds her lover of her yearning and urges him not to break his promise. Therefore, if he follows her suggestion to play changxing during his travels, he should see the red dots embedded in the white dice and be reminded of her.

Jin Zhao’s red bean necklace speaks this same love language to Jiang Mu, functioning as an indirect confession of the depth of his yearning, just as Wen Tingyun’s poem relies on wordplay to mask its deeper meaning. The poem’s closing question, “Do you know it, or do you not?” suggests that love remains unspoken, waiting for the right person to understand what has been left unsaid.

Both the modern drama and the classical poem align with traditional Chinese romantic expression, where direct confession is often avoided in favor of subtlety and symbolism. Unspoken yearning is rendered visible through physical tokens — necklace and dice alike.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Rediscovering Wen Tingyun: A Historical Key to a Poetic Labyrinth by Huaichuan Mou.

300 Tang Poems translated by Xu Yuanchong, bilingual Chinese-English edition.

Red Bean of Yearning Bracelet.

Zhao and Mu as Sun and Moon: Poetry Meets Science

The idiom zhaozhao mumu comes full circle in a key poetic exchange in the drama. Jin Zhao and Jiang Mu imagine each other as celestial bodies: Zhao, aligned with dawn and daylight, becomes the sun, while Mu, aligned with dusk and nighttime, becomes the moon.

Jin Zhao voices his fear that they belong to different worlds and are fated never to be together, echoing the line from the Gaotang Fu in which the goddess of Mount Wu describes herself as Morning Cloud at dawn and Wandering Rain at dusk. His words follow a parallel cadence:

“At dawn, Zhao is the sun; at dusk, Mu is the moon. The sun and moon alternate, never to meet again.”(朝为日,暮为月。日月交替,不复相见。zhāo wéi rì, mù wéi yuè. rì yuè jiāotì, bù fù xiāngjiàn.)

After studying astronomy, Jiang Mu shows Jin Zhao that the sun and moon do, in fact, appear in the sky together at certain times. As Earth rotates, the moon orbits Earth, and Earth orbits the sun, there are moments when both sun and moon are visible above the horizon simultaneously.

Jiang Mu then subverts Jin Zhao’s metaphor with this response: “At dawn, Zhao is the sun; at dusk, Mu is the moon. The sun and moon shine together. Dawn after dawn, dusk after dusk, never to be apart.” (朝为日,暮为月。日月同辉,朝朝暮暮,永不分离。zhāo wéi rì, mù wéi yuè. rì yuè tóng huī, zhāozhāo mùmù, yǒng bù fēn lí.)

As actress Esther Yu later writes in a Weibo post about Jiang Mu’s character: “You say the sun and moon must alternate, never to meet again — she insists on proving that natural law is not absolute, that sun and moon shining together is the answer for the two of you. In her heart, love has never been about one-sided protection or salvation. It is about two souls drawing close side by side, illuminating one another as equals.”

In this moment, ‘Speed and Love’ fuses science with the idiom zhaozhao mumu — from dawn to dusk, day and night, every day — to claim that love, like the sun, moon, and nature itself, is far more flexible than we are taught to believe. There is always room for coexistence, and an exception to every rule.

Cultural Lessons: The Language of Yearning

What unites these cultural expressions, from Warring States idiom to Tang and Song Dynasty poetry, Ming Dynasty tales, and a modern romantic drama, is a shared language of yearning communicated through carefully chosen symbols waiting to be understood — the art of embedding emotion within objects, wordplay, and metaphor for someone attentive to recognize and decode.

‘Speed and Love’ positions itself within this literary tradition. Jin Zhao and Jiang Mu, as dawn and dusk, sun and moon, day and night, embody the faith that parting is not ending, that devotion transcends distance, that two people can run toward each other even when circumstances pull them apart. They understand each other beyond words.

And in separation, there is the essential work of maintaining one’s own life and sense of self: yearning without losing oneself entirely to the yearning.

Zhaozhao mumu is a whisper from thousands of years ago that echoes into the present, both blessing and promise.

朝朝暮暮,永不分离。

zhāozhāo mùmù, yǒng bù fēn lí.

Dawn after dawn, dusk after dusk, never to be apart.