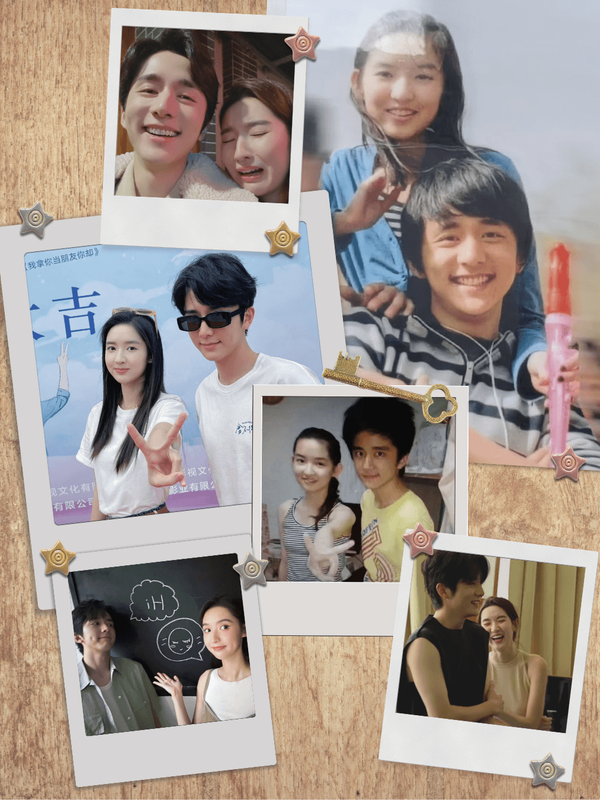

Zhang Xincheng and Wang Yuwen’s on-screen chemistry in You Are My Lover Friend feels both natural and unforced. In the drama, they play childhood friends who gradually develop a romantic bond in adulthood. Their performances have an unmistakable lived-in quality, as though they lived and breathed it rather than just rehearsed it on set, like method actors who spend months cohabiting before filming to capture an intimacy that cannot be faked.

That sense of ease falls into place when we trace their history. The two have known each other for over sixteen years, and counting, since their school days in Beijing, where they trained in dance and musical theater. With common roots in Hubei, their friendship grew around shared family meals and weekends spent commuting to lessons.

As theater kids, their shared love of performing — and the demanding rehearsals and classes that came with it — forged a bond that has endured through the highs and lows of building careers in the same entertainment industry, a bond that now flows into the rapport we see on-screen.

A Serendipitous Casting Call

When casting began for ‘You Are My Lover Friend,’ the producers had no idea that Zhang Xincheng and Wang Yuwen had been friends for sixteen years.

Xincheng received the script first, and soon after, Yuwen messaged him in disbelief.

“Is this real?” she asked.

“Indeed,” he replied.

It was only later that Wang Yuwen revealed to the astonished producers that she and Zhang Xincheng had known each other since seventh and eighth grade, respectively.

What followed was a rare full-circle moment: their first collaboration playing childhood friends after many years of real-life friendship, taking them back down memory lane as classmates and neighbors.

Life in a Tongzilou

Zhang Xincheng asks Wang Yuwen if she remembers where they first met.

“Hai’er Zhao,” she replies without hesitation. “Definitely Hai’er Zhao.”

Their friendship began in 2009 at Hai’er Zhao (海二招 Hǎi’èr Zhāo), short for the Navy’s Second Guesthouse (海军第二招待所 Hǎijūn Dì’èr Zhāodàisuǒ), a red-brick walk-up apartment in Beijing’s Xicheng district. The building was a mid-century tongzilou (筒子楼 tǒngzilóu), which means ‘tube building,’ named for its long central corridor lined with rows of identical units.

These blocks, built in the 1950s–1970s as part of Beijing’s earliest public housing projects to address housing shortages quickly, were modeled on Soviet-era designs common across Central and Eastern Europe.

Like many others, their families had relocated to Beijing so their children could attend reputable schools in the capital. To save on costs, parents often rented units in tongzilou, which had become typical dormitory housing near schools.

“Dozens of families lived on one level,” Wang Yuwen recalls.

Communal Kitchens and Shared Heritage

Though often small and rundown, tongzilou units fostered a strong sense of community. Residents from different cities and towns, from diverse backgrounds and walks of life, mingled and connected within these blocks.

Communal kitchens were the heart of life in a tongzilou, where neighbors showcased their cooking skills. As people far and near prepared their favorite dishes, the smell of food wafting through the tubular corridors often gave away who was at the stove.

For Zhang Xincheng and Wang Yuwen, whose families both hailed from Hubei province in central China, those kitchens became a natural meeting point.

“The kitchens were communal, so we’d take turns cooking,” says Yuwen. “Sometimes his dad would cook, sometimes my mom. Everyone ate together. Then we kids would run back to class after lunch. That warm feeling of going home to eat after class is something I always associate with youth.”

They bonded over familiar Hubei flavors that reminded them of home — regional specialties including hot dry noodles (热干面 règānmiàn), beef rice noodles (牛肉粉 niúròufěn), and sugar-oil pancakes (糖油饼 tángyóubǐng), along with home-style comforts such as ribs and steamed fish.

Although Xincheng and Yuwen were a year apart in school, they spent a great deal of time together outside of class, commuting between home and school, sharing meals with their families, helping with assignments, and looking out for each other. Because their families lived so close, a kind of mutual caretaking arrangement formed. Xincheng often gave Yuwen a lift home on his bike along a safe route that their parents had mapped out.

“They treat the two of us as their own kids,” Wang Yuwen remarks of their parents.

This sense of shared history carried over into their drama, where the co-stars opted to use their hometown Wuhan dialect for playful exchanges, in place of the Cantonese and Fujian dialects originally written into the script.

Weekend Classes, ft. Liu Haoran

Zhang Xincheng and Wang Yuwen spent their formative years training at the Affiliated Secondary School of Beijing Dance Academy. Founded in 1954, it is China’s first secondary dance school, attracting students from across the country to study ballet, Chinese dance, ballroom dance, and song-and-dance performance.

While Wang Yuwen’s character Tang Yang helps Zhang Xincheng’s Jiang Shiyan with his schoolwork in the drama, it was more often the other way around for the two actors during their school days, since Xincheng was a year ahead in school.

“Piano, guitar, drums, synths, songwriting,” Yuwen lists the many things that Xincheng has excelled in over the years.

“I can do it all too, but none of it well,” she quips. “How did I learn? By tagging along to his classes.”

When Xincheng’s parents enrolled him in extracurricular tuition classes, Yuwen’s parents followed suit and signed her up for the same ones.

“Liu Yuan also attended those English classes,” Xincheng adds.

Liu Yuan, better known by his stage name Liu Haoran, was in the same year as Wang Yuwen and came along for the ride.

“Me and Haoran were literally not on his level!” Wang Yuwen laughs.

“But our families thought it was convenient,” she adds. “They figured he (Xincheng) could take us along to all his different classes… so every Saturday or Sunday, we’d take the bus, then the subway, then another bus or something. It was pretty bothersome just to get to English class and study ‘New Concept English.’”

The all-too-familiar ‘New Concept English’ textbooks by British scholar L. G. Alexander, especially the 1997 revised edition designed for Chinese learners, became a national fixture and a shared memory for generations of students.

And so, before the trio became famous actors, young Steven Zhang, Uvin Wang, and Turbo Liu spent their weekends learning English and hopping from one lesson to the next.

“After English class, we’d go to another class,” Yuwen recalls. “Our schedule for the entire day was to follow him around. Haoran and I were the more slack, laidback ones. We didn’t really know what was going on, but we tagged along anyway.”

Parallel Careers and Mutual Friends

After secondary school, Zhang Xincheng entered the Central Academy of Drama, while Wang Yuwen chose Beijing Dance Academy. Yet, both opted to major in musical theater and pursued careers as actors in film and television.

They call this trajectory “miraculous, serendipitous, and hard to come by.”

There were stretches when their schedules were too hectic for them to catch up in person, and their friendship turned into one of exchanging likes over the internet. Yet their bond endured, preserved in time. Their parents stayed in touch, helping bridge the gaps.

Recently, for instance, when Yuwen’s mother’s colleagues asked for Xincheng’s autograph, his mother printed the photos, passed them to Yuwen’s mother, who gave them to Yuwen, who delivered them to Xincheng to sign — before the bundle finally made its way back to Yuwen’s mother.

“It’s like a family baton relay,” Yuwen laughs. A collaborative team effort.

Overlapping circles from school and work reinforce their friendship.

“We have too many mutual friends,” Xincheng grins. “Pretty much everyone she knows, I’ve known since I was little.”

Yuwen nods. “We often hang out with the same close group.”

Asked if those friends have been following their on-screen romance, Wang divulges with a smile, “To this day, they don’t dare watch.”

“When we shared the trailer, our teacher gave it a like,” she adds.

Their teacher would surely be proud. Two kids who once played in the same hallway and spent hours rehearsing in front of the mirrors at the same dance school are now celebrities and, for the first time, co-stars. What are the odds of that?

Improvising with Childhood Memories

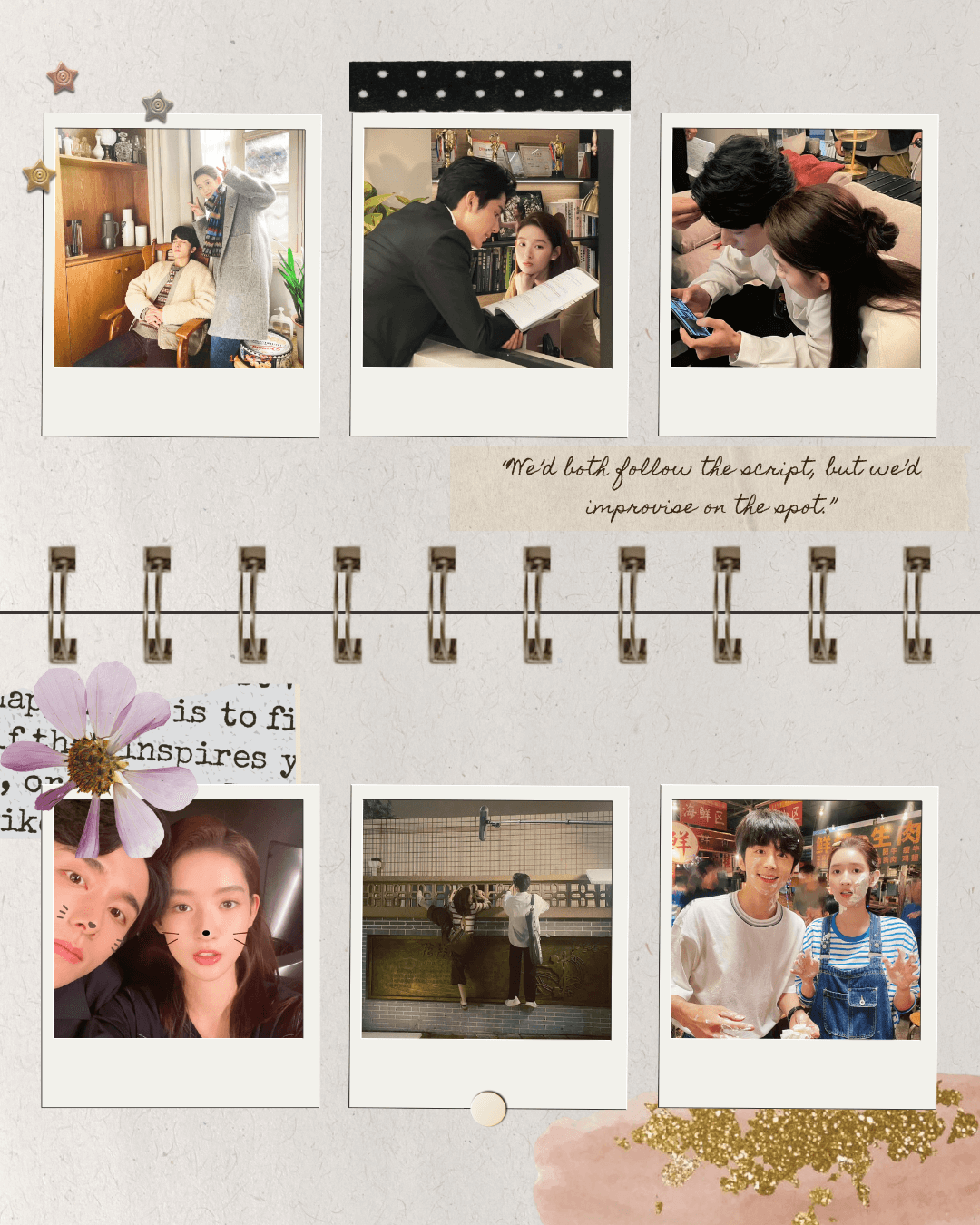

On set, Wang Yuwen and Zhang Xincheng found their characters coming to life organically. Many onscreen moments were impromptu, guided by instinct and shared memories of growing up together.

“We’d both follow the script, but we’d improvise on the spot,” Yuwen says.

She reaches for a food metaphor to explain it, describing their collaboration with the Chinese idiom tian you jia cu (添油加醋 tiān yóu jiā cù), literally ‘adding oil and vinegar,’ an expression that refers to embellishing a story with more color and flavor.

For Yuwen and Xincheng, it meant adding their own figurative sauces and seasonings to the script — inside jokes, knowing glances, and unspoken cues, nurtured over years of friendship.

Director Zhang Tong encouraged their spontaneity, often letting the camera roll until the actors had fully explored the moment.

“The director wouldn’t call ‘cut,’” Yuwen recalls. “We’d just keep going until he said, ‘Got it, you’re good.’”

The co-stars finish each other's sentences and could easily pass for a crosstalk double act performing xiangsheng (相声 xiàngsheng), the traditional Chinese comedy form with folk roots, built on rapid-fire banter between two performers.

“It’s like a reflex,” Yuwen laughs. “Sometimes I don’t even want to respond, but my mouth is faster than my brain.”

The combination of professional training and a longstanding friendship meant that playing friends-to-lovers rarely felt awkward.

“We’ve been doing this since we were little,” Xincheng reflects. “Every day we filmed homework assignments with classmates, playing all kinds of characters. Acting together is just part of our rhythm.”

But neither could keep a straight face during the kiss scenes. Whenever they had to hold a tender gaze, they would burst into laughter.

“You can’t rush it!” Yuwen admits. “Since it was our first time playing lovers, it felt a bit awkward. Even just looking into each other’s eyes was funny, and when it came to filming kiss scenes, I couldn’t bring myself to do it.”

Director Zhang Tong embraced their genuine reactions and even kept a take where the two broke into laughter after locking eyes during a goofy improvised moment.

“Old friends are like this,” he notes with amusement.

Their spontaneity adds an air of yanhuoqi (烟火气 yānhuǒqì) to the drama — that is, the ‘smoky-fire atmosphere’ of everyday life. It’s the crackling warmth of familiarity and unfiltered candor, of inside jokes peppered with the flavors of the hometown culture they share.

The Seven Essentials of Daily Life

That blend of real life and make-believe came together in another way behind the scenes when they invited their families to visit.

“Our parents were even happier than we were,” Yuwen says of the moment their parents learned she and Xincheng would finally collaborate onscreen. “They formed a little group and came to Chengdu to accompany us while we filmed. Xincheng even paid out of his own pocket to plan the trip for them.”

Zhang Xincheng also organised an itinerary for their parents to travel through Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan.

What makes them work so well together on set is that they can be themselves around each other. They create a safe space where they show up as they are, and they look out for each other in small ways. As they tell it, if one of them starts putting on airs or acting too uptight in public, the other will immediately call it out and tease them about their so-called ‘idol baggage.’

In Chinese slang, ‘idol baggage’ (偶像包袱 ǒuxiàng bāofu) pokes fun at celebrities for being overly image-conscious and holding back from doing anything silly or relatable, like pulling an ugly face, acting goofy, or making fun of themselves, for fear of ruining their image and looking uncool.

Wang Yuwen and Zhang Xincheng’s down-to-earth interactions, unburdened by ‘idol baggage,’ shine during promotion too. On their guest episode of the chat variety show Mao Xue Woof (《毛雪汪》Máo Xuě Wāng), the co-stars cook a wholesome meal together while trading playful jabs.

At one point, as Yuwen throws together a stir-fry, she announces, “Last dish — very quick!”

Xincheng watches as she adds a few drops of oil into the pan and remarks, “Only that little bit of oil?”

“I don’t like adding oil,” says Yuwen.

“If I’d known earlier, I wouldn’t have washed my face this morning,” Xincheng teases.

“You’re greasy enough already,” Yuwen shoots back. “You emit the aura of ‘greasy matter’” (油物 yóuwù). Her cheeky dig here is a pun on ‘stunner’ (尤物 yóuwù), a term for a rare beauty or extraordinary figure.

They share the same offbeat sense of humor, often leaning into the absurd.

When asked what roles they might take on next together, Xincheng suggests Mario and Luigi.

“What if I want to be a mushroom?” Yuwen counters.

Eventually, they land on something more abstract — dark soy sauce (老抽 lǎo chōu) and light soy sauce (生抽 shēng chōu).

They even come up with a title: ‘The Adventures of Soy Sauce’ (《酱油历险记》Jiàngyóu Lìxiǎnjì).

Their whimsical banter reveals a more profound meaning embedded in their cultural heritage.

Soy sauce is one of the ‘seven essentials’ of daily life in Chinese culture, according to the well-known phrase, ‘firewood, rice, oil, salt, sauce, vinegar, and tea’ (柴米油盐酱醋茶 chái mǐ yóu yán jiàng cù chá), which we can trace back to the Song dynasty memoir ‘Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital’ (《东京梦华录》Dōngjīng Mènghuá Lù).

Like dark soy sauce, which is richer and sweeter, and light soy sauce, which is saltier and sharper, Zhang Xincheng and Wang Yuwen embody two distinct flavors that are indispensable in different dishes and complement one another when combined. Each brings out the best in different ingredients as they do in a slow-burn, slice-of-life, friends-to-lovers drama, seasoning the story with just the right flavor from daily life to turn it into a believable fairytale.