At first glance, the drama’s English title, ‘The Vendetta of An,’ delivers the straightforward promise of a revenge story. Looking closer, we find that its vendetta concerns two “An’s”: our main protagonist Xie Huai’an (Cheng Yi) and the imperial capital of Chang’an, where the action unfolds.

But it is the Chinese title, Chang’an Ershisi Ji (《长安二十四计》Cháng’ān Èrshísì Jì), meaning ‘Twenty-Four Stratagems of Chang'an,’ that unlocks the drama’s true ambition. This title combines the number “twenty-four” (二十四 èrshísì) from the twenty-four solar terms of the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar with “stratagems” (计 jì) from the ‘Thirty-Six Stratagems’ (三十六计 Sānshíliù Jì) of classical military wisdom.

The drama embeds the solar terms and stratagems as narrative devices, forming the foundation for its plot, pacing, mood, and themes. By building plot twists on authentic strategic logic and using seasonal markers to foreshadow events and establish atmosphere, the drama transforms familiar revenge beats into something that feels organic rather than manufactured for shock value.

This approach deepens our cultural appreciation while expanding narrative possibilities. It demonstrates how traditional knowledge systems can be reimagined as storytelling frameworks that drive plot and character development beyond familiar Western narrative structures.

The Hero’s Journey has its place, but here we find a different architecture — one less concerned with triumphant milestones as markers of progress and transformation. Rather, the drama offers a nuanced meditation on survival, irreversible consequences, and what remains when vengeance becomes the only reason you permit yourself to live.

‘Twenty-Four’ From Solar Terms

The twenty-four solar terms (二十四节气 èrshísì jiéqì) are a traditional Chinese calendrical framework developed through observing the sun’s movement and tracking seasonal transitions, including temperature shifts, precipitation patterns, and other changes in the natural world over the course of the year.

Often regarded as China’s fifth great invention after paper, printing, gunpowder, and the compass, the solar terms emerged from early agrarian observations of solstices and equinoxes, then expanded into a more comprehensive framework during the Spring and Autumn period before being refined and standardized during the Qin and Han dynasties.

The finalized system divides the sun’s 360° ecliptic path into twenty-four equal segments of 15°, each solar term marking a specific point in the seasonal cycle. This annual cycle runs from the Beginning of Spring (立春 Lìchūn), starting around February 3-5, to the Greater Cold (大寒 Dàhán) around the following January 20-21.

Over millennia, the solar terms have provided practical guidance for agriculture, health, and wellness, allowing communities to adapt farming practices, establish festivals and customs, and transmit folklore and conventional wisdom across generations.

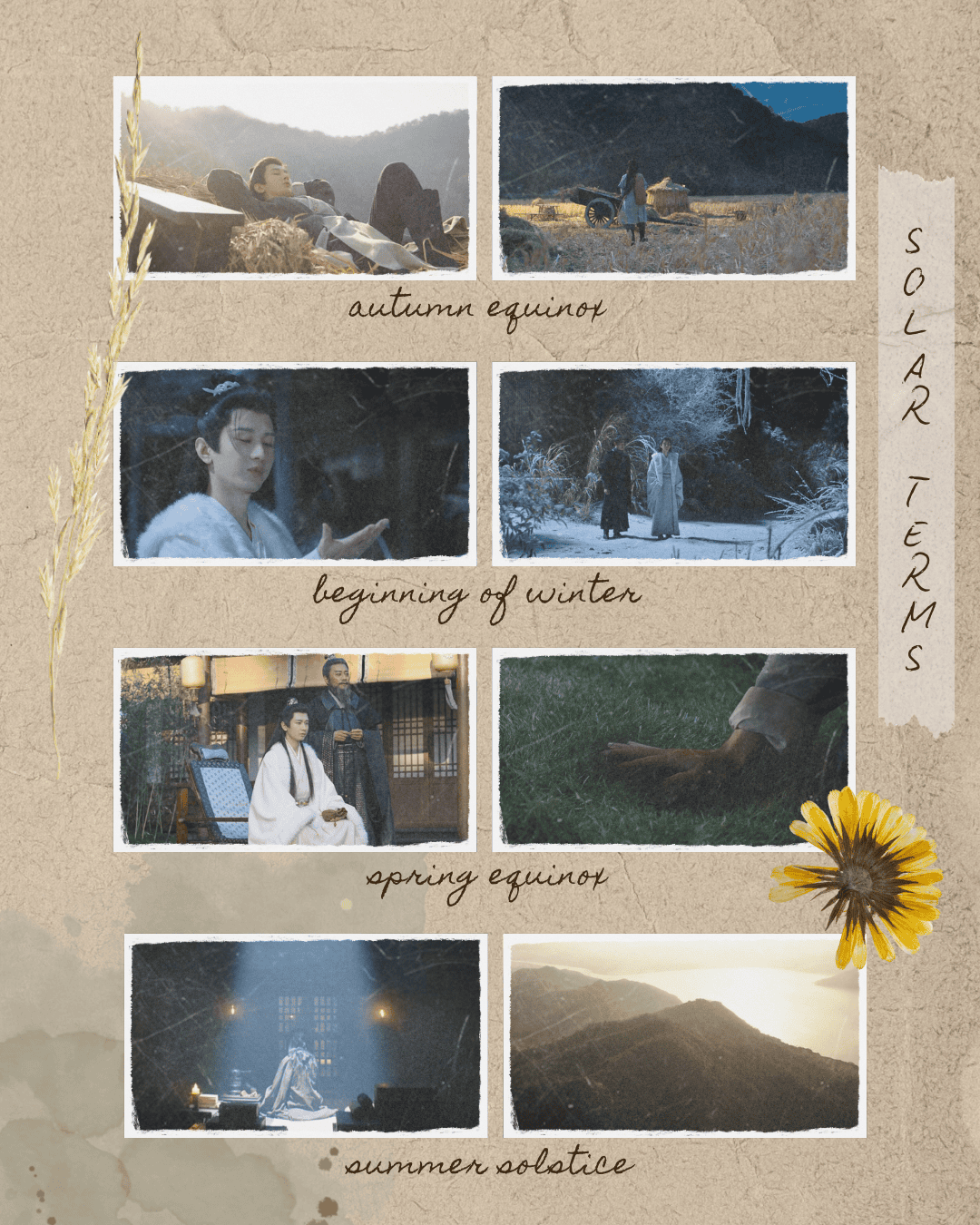

In ‘The Vendetta of An,’ the solar terms shape the drama’s mood and atmosphere. Specifically, the Autumn Equinox (秋分 Qiūfēn), the Beginning of Winter (立冬 Lìdōng), the Spring Equinox (春分 Chūnfēn), and the Summer Solstice (夏至 Xiàzhì) establish the emotional landscape at pivotal moments in Xie Huai’an’s journey, with each term’s characteristics foreshadowing events to come:

Autumn Equinox (Qiufen)

The midpoint of autumn usually arrives on September 22-24. Clear skies, chillier winds, and plants start to dry and wither. There can be drought in the southern countryside where Huai’an resides. There is a perfect balance of yin and yang at this time, often making it the most comfortable period of the year, but this also means the balance will begin to tip from here. An atmosphere of elegiac melancholy settles over the land, and it’s important to remain optimistic and calm during this season. The atmosphere of this solar term matches Huai’an’s state of mind as he prepares to say goodbye to the countryside and return to Chang’an for revenge.

Beginning of Winter (Lidong)

Winter usually begins on November 7-8 as lakes and ponds start to freeze over at the surface while remaining fluid below. Since the Zhou dynasty, as recorded in the ‘Book of Rites’ (《礼记》Lǐjì), emperors wore furs in observance of this season. Just as Huai’an cooks for his friends, families often fortify themselves with hearty meats and fresh vegetables, preparing for leaner days ahead. In ancient times, authorities associated winter’s rising yin energy with a rise in crime and shady schemes, and so they implemented rites to curb such behavior.

Spring Equinox (Chunfen)

The midpoint of spring usually arrives on March 19-22, with an equal division between day and night. The body relaxes in the warming weather, yet as depicted in the drama, there can be one last cold snap before winter departs. A folk proverb warns: “Once spring begins, don't rejoice too soon — there are still forty days of cold weather ahead” (打了春,别欢喜,还有四十天冷天气 dǎ le chūn, bié huānxǐ, hái yǒu sìshí tiān lěng tiānqì). It’s important to stay vigilant about keeping warm to avoid getting sick.

Summer Solstice (Xiazhi)

The summer solstice usually falls on June 20-22 and marks the longest day and shortest night of the year. Deers, which are considered animals with yang energy, shed their antlers, indicating the rise in yin energy. Meanwhile, cicadas are reborn and ascend from the ground to the treetops, symbolizing transcendence, which is a tonal match for the drama’s finale. This solar term calls for vigilance and preventative care. Traditional Chinese medicine teaches treating winter illnesses during summer, expelling excess cold from the body at the hottest time of the year. Similarly, Huai’an prepares to purge the cold darkness lurking in Chang’an. As shown in the drama, people celebrate the summer solstice with noodles, dumplings, or wontons.

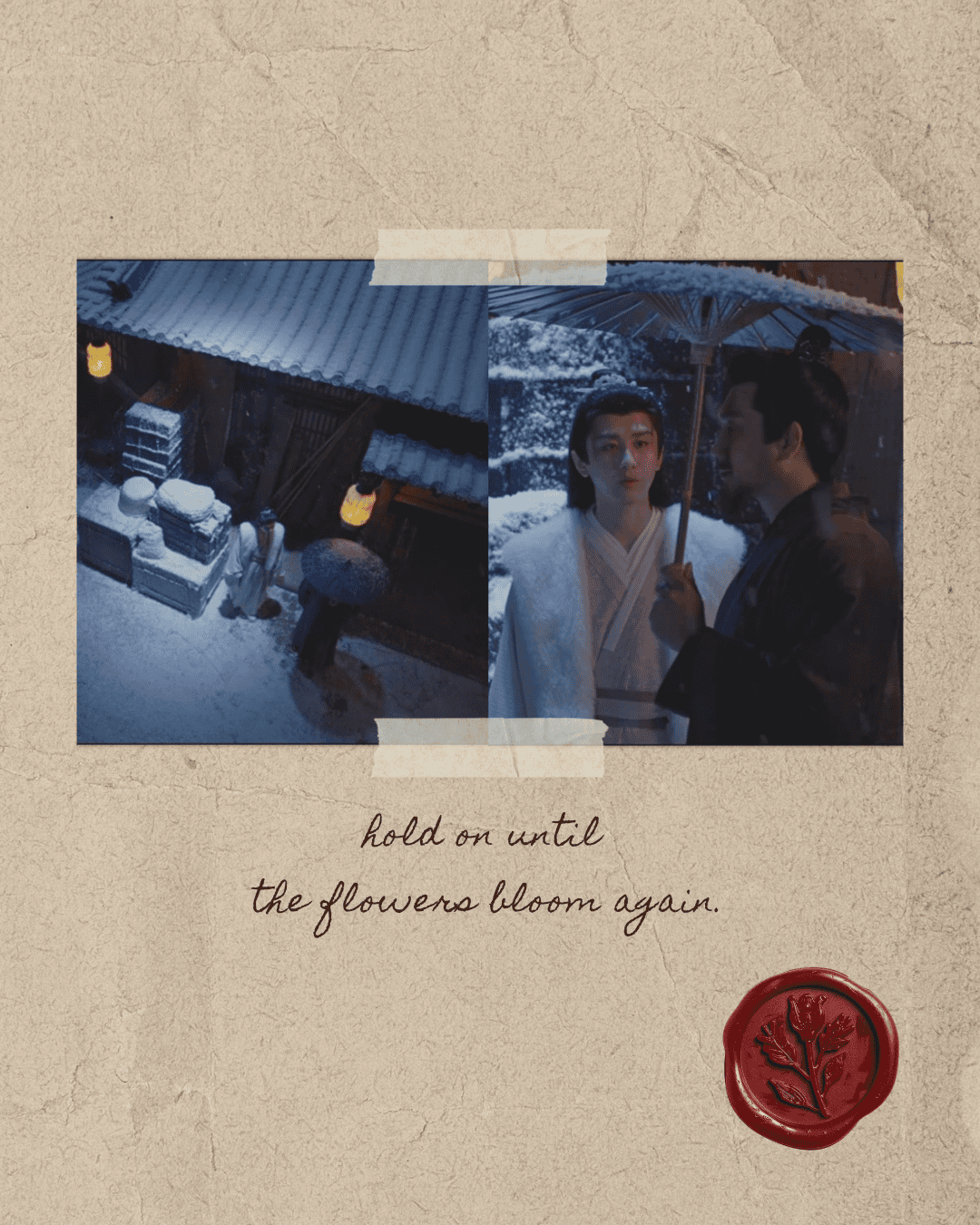

While the solar terms promise cyclical renewal — cold gives way to warmth, snow thaws, flowers blossom — ‘The Vendetta of An’ doesn’t portray revenge as cathartic release but as snowfall that never truly ends. Even as the calendar advances to the Spring Equinox, Xie Huai’an is literally and metaphorically pulled back into lambing snow, a late cold snap as winter refuses to release him from its icy grip.

Through Huai’an’s subtle facial expressions, we watch him dying a little inside each time he achieves a goal. There is no satisfying victory or release, only reminders of trauma and pain that linger.

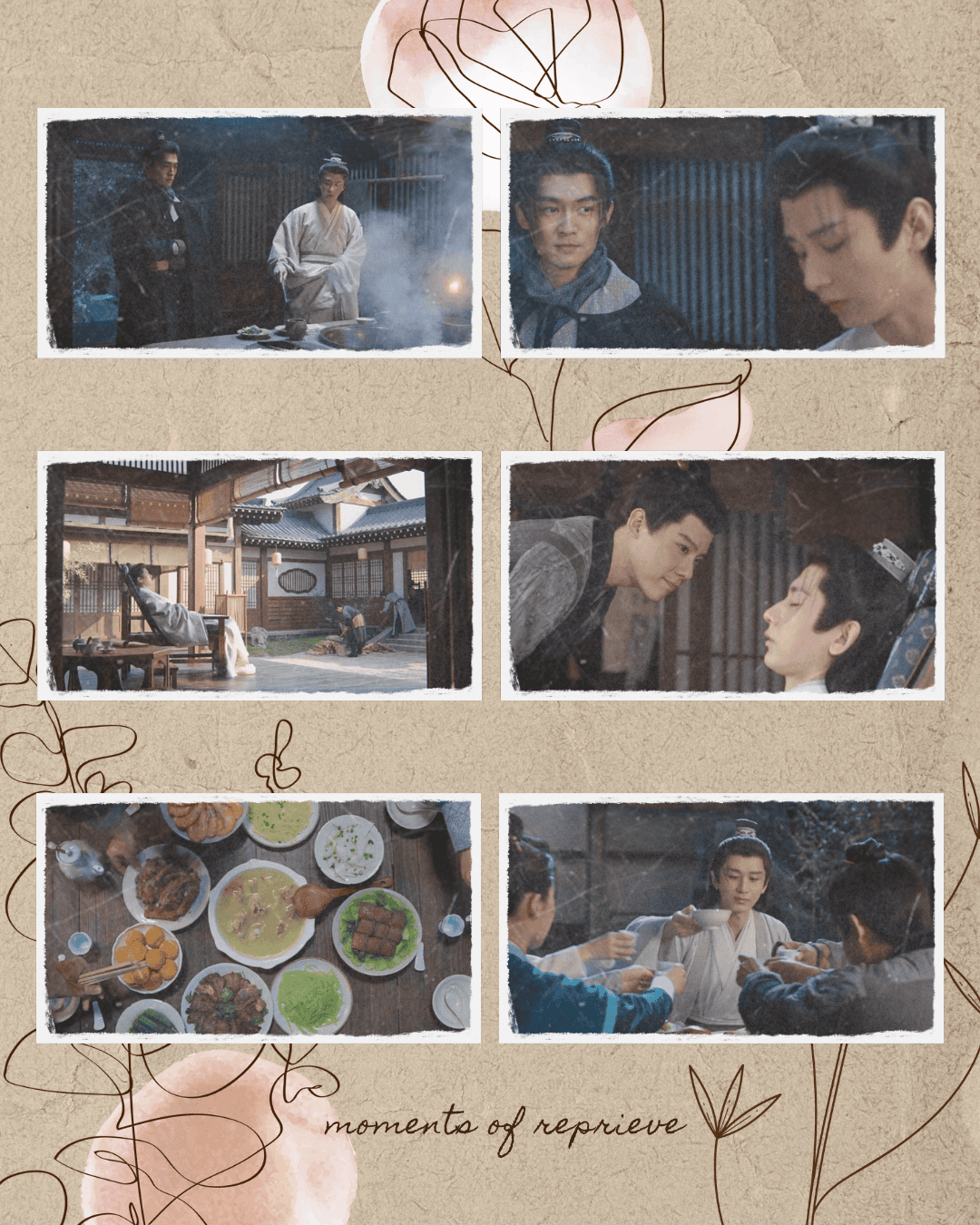

Even with brief moments of reprieve alongside his friends Ye Zheng (Tong Mengshi), Xiao Wenjing (Zhou Qi), Shen Xiaoqing (Wang Zixuan), and his sister Bai Wan (Xu Lu), while he recuperates in his chair in the garden, and cooks and shares seasonal meals, Huai’an does not permit himself the luxury of experiencing the seasons in their fullness, of living within the present moment, of stopping to smell the roses.

To Huai’an, what he has lost cannot be restored by any turning of the seasons. That tension becomes central to the story: time moves on, even when a person cannot.

For an interesting guide to the twenty-four solar terms, James W. Murphy’s book is a recommended pick:

The 24 Solar Terms: Mythology, Folkways, and Poetry of the Chinese Nature Almanac

by James W. Murphy

In his mind’s eye, Huai’an sees his father Liu Ziwen (Huang Jue) telling him, “You’ve already done so well. Can you keep on living? Perhaps hold on a little longer. Hold on until next year, when the flowers bloom again. It’s just that I believe my son deserves to see the flowers bloom once more.” (“你已经做得很好了,还能活下去吗?要不再坚持一段时间,坚持到明年花开的时候。只是觉得,我儿子值得再看一次花开。” nǐ yǐjīng zuò de hěn hǎo le, hái néng huó xiàqù ma? yàobù zài jiānchí yí duàn shíjiān, jiānchí dào míngnián huā kāi de shíhòu. zhǐshì juéde, wǒ érzi zhíde zài kàn yí cì huā kāi.)

As actor Cheng Yi writes in a Weibo post to his character:

Xie Huai’an, your father said he hoped you would be able to see the flowers bloom once more.

In a dream, your father asked you to wait a little longer. After the flowers bloom, you can wait a little longer still. If you have the courage and patience to keep waiting, then live out your life calmly and steadily.

What’s painful is … the loving care once given to that boy was real, yet the hatred left behind by the schemes is also real. You — or that boy once called Liu Zhi — did not nod in agreement in the dream.

On the surface, it sounds like a very good life.

But it is not the life you would choose.

When Huai’an reunites with his sister, she reveals her hopes for him through a painting she has drawn: “The brother in this painting represents my selfish wish. I hope he can grow flowers, feed a cat, doze off under the veranda, and live his days in peace — even if only for one day.” (“这画中的哥哥,是我的私心。 希望他能养花,喂猫,在廊下打盹,平静地过日子,哪怕一日也好。” zhè huà zhōng de gēge, shì wǒ de sīxīn. xīwàng tā néng yǎng huā, wèi māo, zài lángxià dǎdǔn, píngjìng de guò rìzi, nǎpà yí rì yě hǎo.)

Yet such peace feels out of reach. Huai’an only survives by clinging to memories of his loved ones with tunnel-visioned purpose: to keep them alive in his mind, and to avenge them. Vengeance becomes the only justification for his continued existence.

Survivor’s guilt weighs on his soft heart. Beneath his steely surface remains an inherent kindness and a sensitive soul with no room to breathe.

’Stratagems’ From ‘Thirty-Six Stratagems’

The ‘Thirty-Six Stratagems’ represent one of China’s most influential compilations of strategic and tactical thinking. The text crystallized during the Ming and Qing dynasties, drawing on earlier military treatises including Sun Zi’s The Art of War (《孙子兵法》Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ) from the Spring and Autumn period, ‘Master Wei Liao’ (《尉繚子》Wèi Liáozi) and tactical insights of Wu Qi from the Warring States period, the strategic wisdom of Zhuge Liang of the Eastern Han and Three Kingdoms period, as well as foundational concepts concerning the interplay of opposing forces from yin-yang theory found in the I Ching (《易经》Yìjīng), also known as the ‘Book of Changes.’

The compilation comprises six sets of stratagems: Stratagems for Advantageous Situations (胜战计 shèngzhàn jì), Stratagems for Engaging the Enemy (敌战计 dízhàn jì), Stratagems for Attacking (攻战计 gōngzhàn jì), Stratagems for Confusion and Chaos (混战计 hùnzhàn jì), Stratagems for Gaining Ground (并战计 bìngzhàn jì), and Stratagems for Desperate Situations (败战计 bàizhàn jì). The first three sets address scenarios where the strategist holds the advantage, while the latter three apply when at a disadvantage. With six stratagems in each set, we arrive at the titular thirty-six.

That said, the number thirty-six is more symbolic than strictly literal. In the yin-yang theory of the ‘I Ching,’ even numbers are yin and odd numbers are yang. The number six represents yin — associated with darkness and, by extension, concealment and the shadowy calculations of warfare and tactical deception. In the ‘I Ching,’ yin is represented by broken lines, and a hexagram consists of six lines. When all six lines are broken, the result is pure yin, representing the receptive, the hidden, the earth.

In the drama, six also corresponds with the six key enemies Huai’an seeks to destroy.

This connection between stratagems and yin is embedded in the Chinese language. The word for plot or scheme is yinmou (阴谋 yīnmóu), literally ‘yin-scheme.’ The character 谋 (móu) and 计 (jì for ‘stratagem’) both denote planning and scheming, reinforcing the association between strategic thinking and yin’s shadowy nature. Thirty-six, as the square of six, amplifies yin’s covert nature, becoming a metaphor for numerous stratagems.

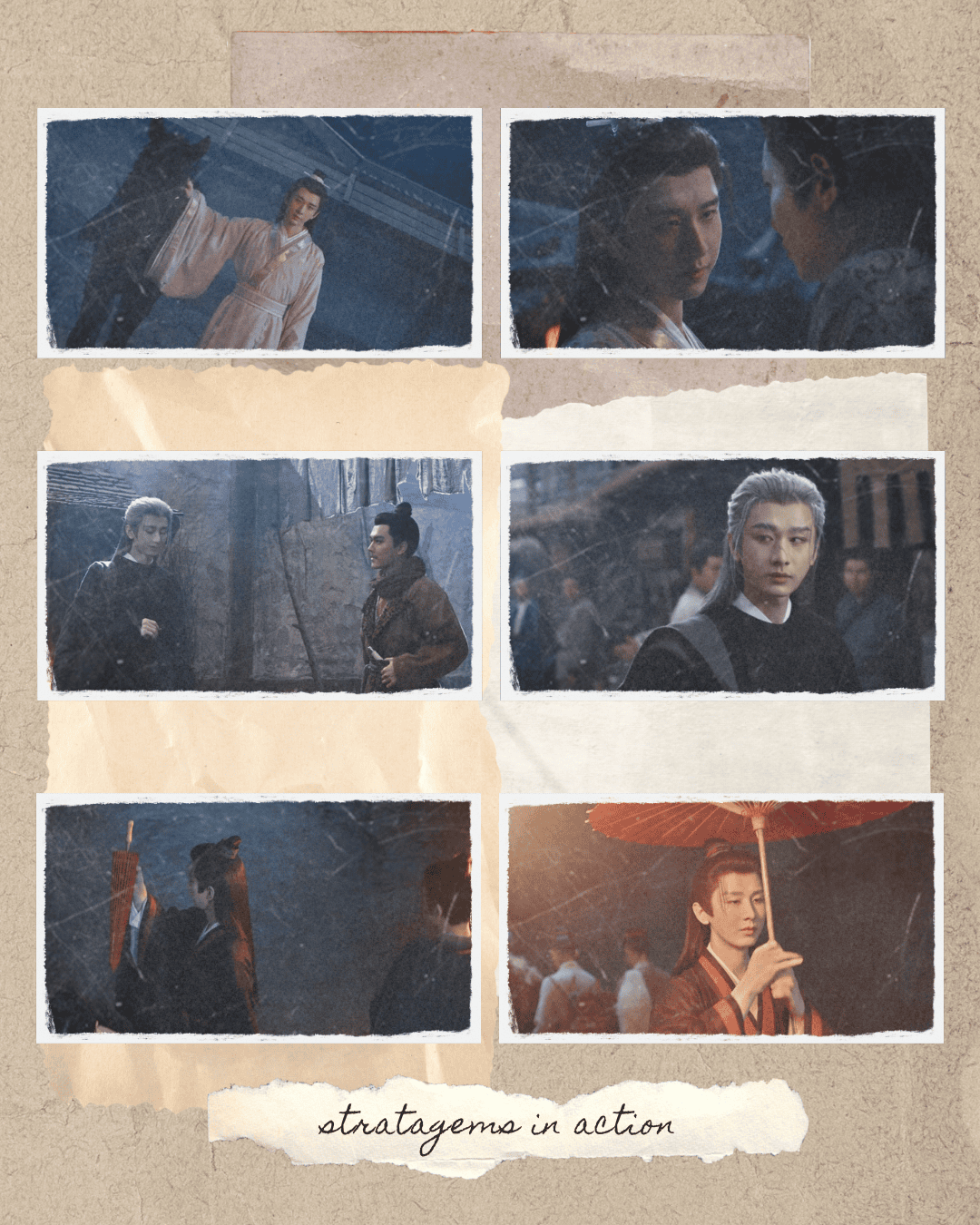

Similarly, the drama’s Chinese title references twenty-four stratagems, though countless tactical moves appear throughout the narrative. Just as Xie Huai’an wields stratagems, so do those around him — allies and adversaries alike. Throughout the drama, characters including Xiao Wenjing, Emperor Xiao Wuyang (Liu Yijun), Wu Zhongheng (Wang Jinsong), Gu Yu (Ye Zuxin), Yan Fengshan (Zhang Hanyu), Zhu Zilong (Cheng Taishen), Cen Weizong (Ni Dahong), Han Ziling (Liu Yitong), Wang Pu (Wang Zuyi), and Su Changlin (Guo Cheng) navigate not just twenty-four discrete moves but an intricate web of stratagems.

It’s also worth noting that many but not all of the stratagems highlighted in posts on the drama’s official Weibo account come from the ‘Thirty-Six Stratagems’ text. Several are Chinese idiomatic expressions and conventional wisdom drawn from other classical writings, including the Classic of Poetry (《诗经》Shījīng, also known as the ‘Book of Songs’), Records of the Grand Historian (《史记》Shǐjì), ‘Records of the Three Kingdoms’ (《三国志》Sānguó Zhì), and Romance of the Three Kingdoms (《三国演义》Sānguó Yǎnyì).

Historically, stratagems have been combined and layered in countless ways, their principles applied beyond the battlefield and political arena to entrepreneurship, gameplay, detective work, stage magic, and more. The text’s cultural impact spans generations, informing practices in economics, diplomacy, the arts, and daily life.

Stratagems are built on the understanding that people rarely see things as they are. We tend to see the world around us as we want it to be, as we need it to be, or as we are told it is. Stratagems operate not by overpowering opponents but by exploiting perceptual biases, guiding what people notice, what they ignore, and how they interpret what they see.

What distinguishes a stratagem from broader strategy is also important: strategy is the big-picture plan, while a stratagem is a tactical move — a scheme, maneuver, or trick — designed to shift advantage in a specific situation.

To cultivate sharper perception and better judgment, Amy E. Herman’s ‘Visual Intelligence’ is worth a read. You’ll learn practical techniques for seeing what others miss in a fun and engaging way through the study of visual art and art history.

Visual Intelligence: Sharpen Your Perception, Change Your Life by Amy E. Herman

‘The Vendetta of An’ frames its narrative through classical stratagems to build dramatic tension, suspense, and surprise. Appearances deceive, allegiances shift, apparent stability conceals imminent upheaval, and nearly every forward step brings reversals. What seemed like complete understanding proves to be only the beginning.

This creates an immersive and interactive viewing experience. We become both observer and participant, constantly reconsidering our judgments as surface assumptions prove incomplete. Seeds planted episodes earlier sprout into view while seemingly minor decisions reveal their weight within a larger design. When twists arrive, they feel logically earned in retrospect, revealing how easily perception can be guided and swayed.

Here is an overview of a stratagem from each set that features in the drama:

When Holding Advantage

Set 1: Stratagems for Advantageous Situations (胜战计 shèngzhàn jì)

- Deceive the Heavens to Cross the Sea (瞒天过海 mántiān guòhǎi)

- Carry out your intended action openly in plain sight, making it appear so routine and ordinary that it slips under the radar, fooling even the heavens or the emperor.

Set 2: Stratagems for Engaging the Enemy (敌战计 dízhàn jì)

- Openly Repair the Plank Roads, Sneak Through Chencang (明修栈道,暗渡陈仓 míng xiū zhàndào, àn dù Chéncāng)

- Make visible preparations in one direction as cover while secretly advancing through another route entirely.

Set 3: Stratagems for Attacking (攻战计 gōngzhàn jì)

- Lure the Tiger Down the Mountain (调虎离山 diàohǔ líshān)

- Draw your opponent away from their position of strength to where they are vulnerable.

When at a Disadvantage

Set 4: Stratagems for Confusion and Chaos (混战计 hùnzhàn jì)

- Golden Cicada Sheds Its Shell (金蝉脱壳 jīnchán tuōqiào)

- Preserve a convincing external façade to prevent suspicion while quietly escaping or repositioning beneath the surface.

Set 5: Stratagems for Gaining Ground (并战计 bìngzhàn jì)

- Turn the Tables on the Host (反客为主 fǎnkè wéizhǔ)

- Enter as a guest, gradually assume control from within, and emerge as the master.

Set 6: Stratagems for Desperate Situations (败战计 bàizhàn jì)

- Chain Stratagem (连环计 liánhuán jì)

- Link multiple stratagems together in sequence so each reinforces the others and provides backup if one fails.

If you’re interested in becoming more well-versed in all thirty-six stratagems, Stefan H. Verstappen’s ‘The Thirty-Six Strategies of Ancient China’ is an easy-to-read starting point.

The Thirty-Six Strategies of Ancient China by Stefan H. Verstappen

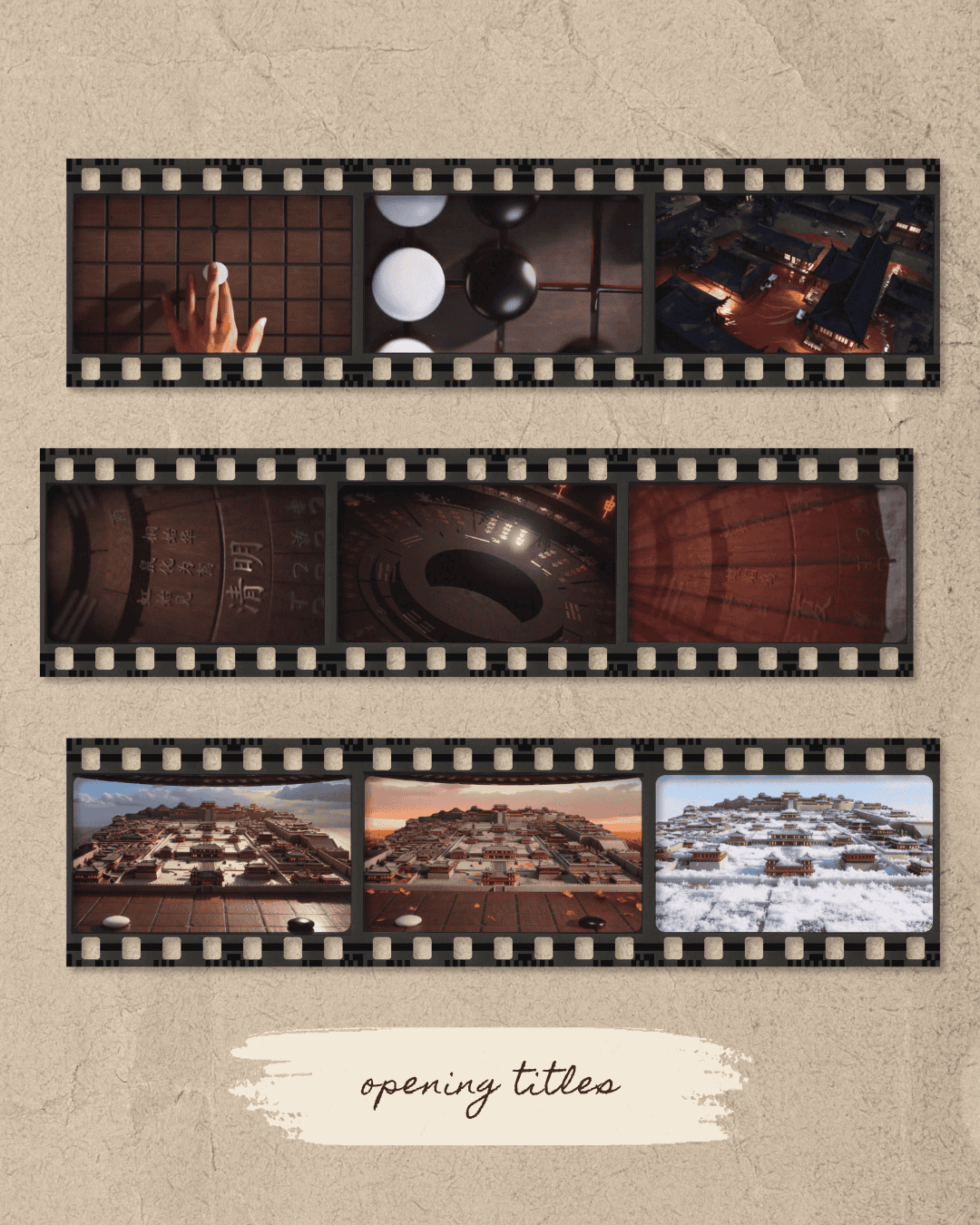

Symbolism in Opening Titles: Weiqi, Stratagems, Time

The drama’s opening title sequence visually introduces the solar terms and stratagems as they intertwine to inform its narrative and emotional landscape.

A hand places a round white stone on a board for the game of weiqi (围棋 wéiqí), known internationally by its Japanese name, Go. This board game originated in China at least 2,500 years ago, its Chinese name literally meaning ‘encirclement board game.’

As the qi (棋 qí) in the four classical cultural arts of qin qi shu hua (琴棋书画 qín qí shū huà) — qin being guqin or zither, shu being calligraphy, and hua being painting — weiqi represents the art of strategic thought. The game and the ‘Thirty-Six Stratagems’ share deep conceptual roots, with players employing many of its principles.

Played on a square grid with black and white stones, players take turns placing a stone on an empty intersection. Stones never move once played, and any stone or connected group of stones surrounded by the opponent is captured and removed. The game ends when both players pass consecutively, agreeing that no further advantageous moves remain, and the winner is the one who controls more territory on the board.

As the title sequence continues, the board representing the city of Chang’an gradually fills with blood. Every move played, every stratagem deployed toward revenge, exacts an irreversible cost that spreads beyond the player, staining the entire city.

The imagery then transitions to a rotating disc engraved with markers of the twenty-four solar terms, combined with stem-branch symbols from the sexagenary cycle (干支 gānzhī), a traditional Chinese calendrical system for timekeeping. One complete cycle spans sixty years. For a person, reaching sixty signifies the completion of a full cycle and a return to the same stem-branch combination as their birth year, a milestone worthy of great celebration. It represents exactly what Huai'an’s family wished for him: to live peacefully into old age.

The twenty-four solar terms complement weiqi as a metaphor in the drama by making time itself an instrument of strategic deception. Stratagems in weiqi rely on patience and accumulation rather than dramatic strikes. Just as seasons shift by degrees, power consolidates quietly, creating the dangerous illusion that nothing has changed until the outcome is already sealed. By the time the opponent realizes they are trapped, they have been living inside the trap for hours.

Yet weiqi is more than victory and defeat. The game reveals much about who you are — your judgment, your thinking, your state of mind, the choices you make under pressure. The board becomes a mirror.

True peace — the ‘An’ (安 ān) in the English title, in Huai’an’s name, and in Chang’an — lies not in mastering the game but in finding the strength to live on out in the world, after the snowstorm, outside the granary, to see the flowers bloom again.

Stratagems impart valuable wisdom for navigating the world, but when they become the only lens through which we see, our vision narrows into an endless cycle of calculation, until we can no longer perceive what else the world could hold for us: natural splendor, love, friendship, and opportunities found on broader horizons.

Symbolism in Closing Credits: Solar Term Landscapes

The drama’s closing credits feature original artwork inspired by traditional Chinese ink-wash landscape painting (山水画 shānshuǐ huà). As the credits roll, the background imagery transitions through seasonal vistas that visually represent the cyclical passage of the twenty-four solar terms. The artworks flow seamlessly from one season to the next, subtly transforming in color, light, and mood — from winter’s snow-laden landscapes to spring’s blossoming flowers against rolling hills and flowing turquoise waters, summer’s lush greenery, autumn’s vibrant golden foliage, and completing the cycle with cooler, muted landscapes of misty mountains and bare trees.

In the drama’s finale, the production team shares this farewell message on screen:

“Even when life brings wind and snow,

Indomitable courage lets us endure until the flowers bloom.

Thank you to every viewer for your companionship.”

纵然人生会有风雪,

zòngrán rénshēng huì yǒu fēngxuě,

无畏的勇气能守到花开。

wúwèi de yǒngqì néng shǒu dào huā kāi.

感谢每一位观众的陪伴。

gǎnxiè měi yī wèi guānzhòng de péibàn.

‘The Vendetta of An’ reminds us that time goes on, and the world keeps turning, regardless of where we find ourselves in the story — and long after the story comes to rest.

Throughout the drama, solar terms and stratagems serve as narrative and thematic architecture that build mood and atmosphere in the moment, and drive plot and character toward more profound endings.

The seasons will cycle through. May we all survive hardship and see the flowers bloom again.