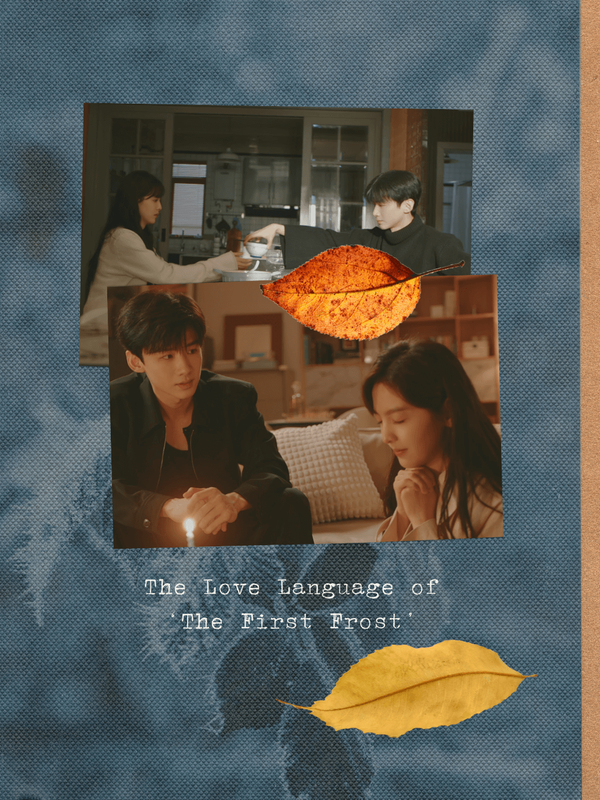

The First Frost, a Chinese romantic drama starring Bai Jingting as Sang Yan and Zhang Ruonan as Wen Yifan, speaks a love language demonstrated through action, in showing up day after day with mindful attentiveness. Action over grand gestures and empty promises. It’s rooted in the traditional wisdom of Frost’s Descent, a solar term in the Chinese lunisolar calendar that centers on tending to vulnerability during periods of change. This philosophy invites us to nourish and soothe our bodies and minds when disruption threatens balance.

Even outside of this seasonal period, Frost’s Descent offers us timeless wisdom we can carry into any season of upheaval. ‘The First Frost’ communicates this fluently, reminding us to care for ourselves and each other when we’re facing trauma, disruption, or uncertainty.

This is a guide to understanding that language — the history, traditions, customs, and symbolism in poetry and art that the drama channels into its love story.

Shuangjiang: What’s in a Name?

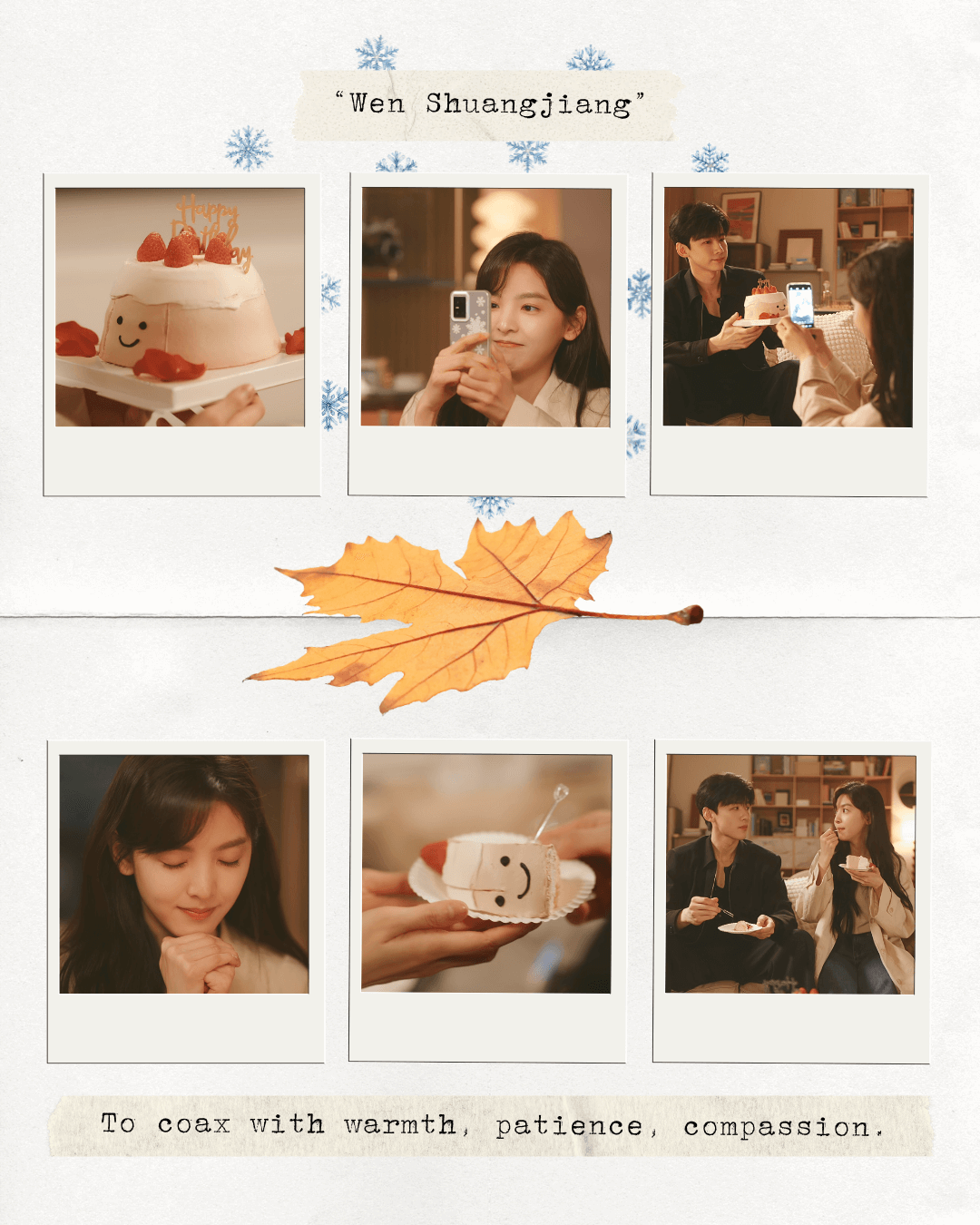

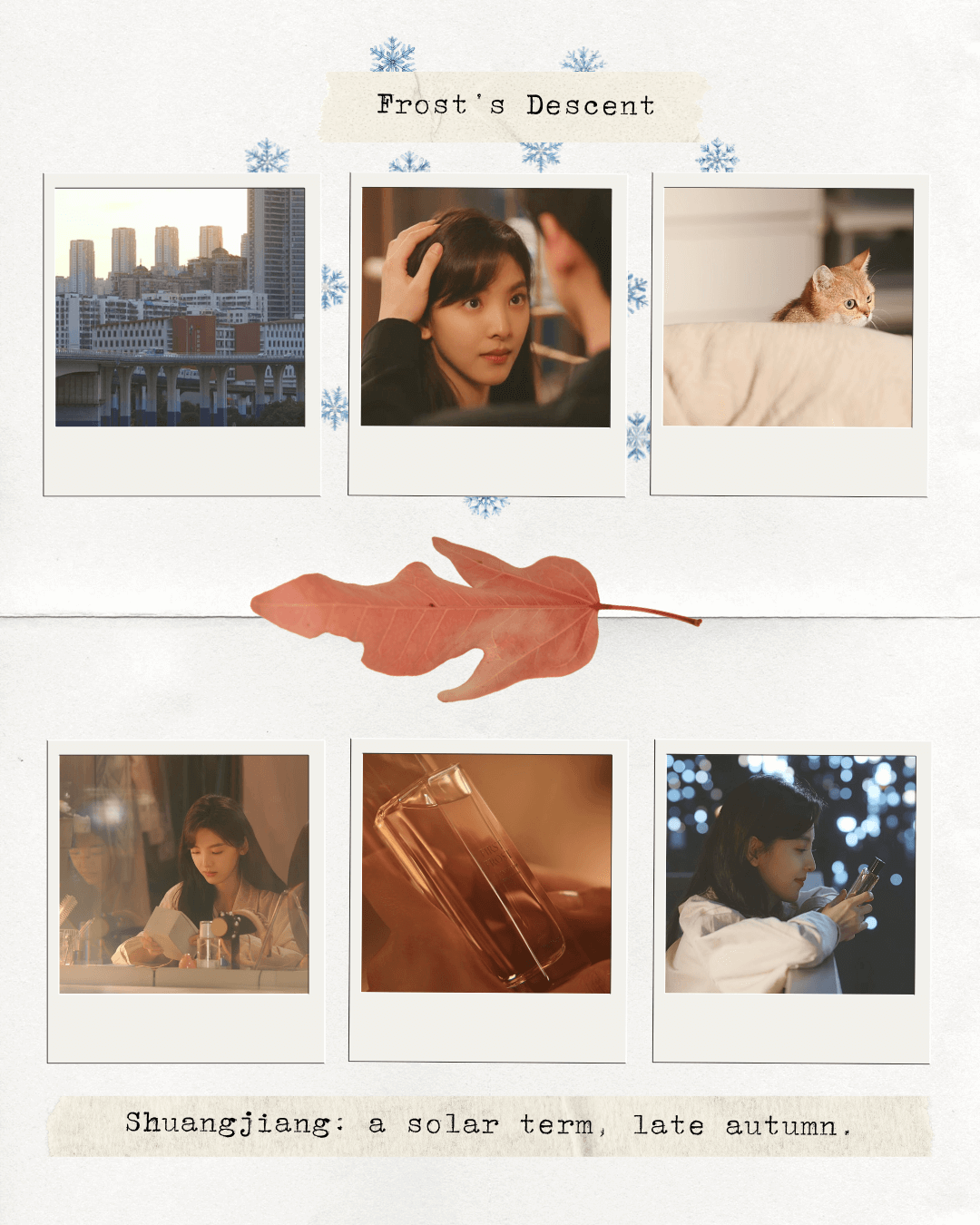

Wen Yifan was given the nickname Shuangjiang by her father because she was born during Frost’s Descent (霜降 Shuāngjiàng), a traditional Chinese solar term. Her nickname carries her father’s blessings and hope that she would receive the patient, mindful care we all need during seasons of change.

This name particularly resonates when paired with her surname, Wen (温 Wēn), a real Chinese surname and the character for ‘warmth.’ Wen Shuangjiang — warmth and frost, together in a single name. The drama explores this duality through both its narrative and visual language.

Sang Yan calls her Wen Shuangjiang, using both her surname and nickname. The way he says it functions almost as a declaration: an acknowledgment that he sees who she is at her core, in all her complexity, and that after all these years, he still remembers and cares.

For her birthday, Sang Yan gives Wen Yifan a bottle of perfume named ‘First Frost.’ This gift shares the drama’s English title, alludes to her nickname, and shows Sang Yan’s attentiveness. He sees her completely and honors what her name signifies.

Wen Yifan’s phone case here is decorated with snowflakes, linking her to Frost’s Descent through the literal visual of falling frost.

‘Hard to Coax’: Thematic Connection to Chinese Title

Adapted from Zhu Yi’s web novel ‘Nan Hong’ (难哄 Nán Hǒng), meaning ‘Hard to Coax,’ the drama retains this title for its Chinese release. The phrase captures an essential aspect of both the philosophy of Frost’s Descent and Wen Yifan’s healing journey.

To ‘coax’ (哄 hǒng) is to soothe, to comfort through gentle persistence, to offer care that doesn’t demand immediate acceptance. Someone who is ‘hard to coax’ requires extra tenderness, patience, and compassion.

Wen Yifan, wounded by trauma and loss, is ‘hard to coax’ back into trust, into warmth, into believing she deserves love and care. The Chinese title doesn’t intend to demean the weight of her experience. Rather, it frames her gradual healing through the lens of romance — a frozen, guarded heart that thaws and opens up over time.

Her healing also requires her to learn to coax herself. To truly heal, she learns to extend the same compassion and gentle persistence inward, engaging in self-care and treating herself with the tenderness she would offer a loved one.

At the same time, Sang Yan has his own coaxing to do. His gaming name, Bai Jiang (败降 bài jiàng), is not the Bai Jiang meaning ‘Defeated General’ (败将, also bài jiàng), but ‘Defeated by Shuangjiang,’ referencing Wen Yifan’s nickname. The name carries his unresolved feelings, the rejection he believed he experienced in their school days, when he thought Wen Yifan had treated him as a ‘backup' rather than a first choice. He, too, needed to coax himself through that wound, to heal his own sense of hurt and grow into a steadier and more understanding person who could reach her again without the armor of wounded pride.

Here, coaxing ourselves means self-compassion rather than self-indulgence. This isn’t easy work, and it doesn’t happen quickly. Sometimes we are the ones who are hard to coax, shaped by our own complex histories and wounds. In these moments, we can choose to tend to ourselves with the same deliberate care that sustains us through difficult seasons.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Handmade Cake Charm inspired by ‘The First Frost,’ made by AeryStudio on Etsy.

Snowflake Jadeite Charm Pendant by JadeUnique (Henry Lee) on Etsy.

Frost’s Descent in the Traditional Lunisolar Calendar

Shuangjiang (霜降 Shuāngjiàng), or Frost’s Descent as it is often translated in English, is the eighteenth of the twenty-four solar terms in the Chinese lunisolar calendar, marking the final phase of autumn before winter begins.

The twenty-four solar terms (二十四节气 èrshísì jiéqì) are a traditional calendrical framework developed through observing the sun’s movement and tracking seasonal transitions, including temperature shifts, precipitation patterns, and other changes in the natural world over the course of the year. Often regarded as China’s fifth great invention after papermaking, printing, gunpowder, and the compass, the twenty-four solar terms were officially inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2016 as a knowledge system of enduring cultural significance.

These solar terms emerged from early agrarian observations of solstices and equinoxes, then expanded into a more comprehensive framework during the Spring and Autumn period before being refined and standardized during the Qin and Han dynasties. The finalized system divides the sun’s 360-degree path along the ecliptic into twenty-four equal segments of 15 degrees each, with each segment marking a distinct seasonal transition.

Over millennia, the solar terms have provided practical guidance for agriculture, health, and wellness, allowing communities to adapt farming practices, establish festivals and customs, and transmit folklore and conventional wisdom across generations. Each term has accumulated its own ecology of foods, health practices, and philosophical ideas.

The Arrival of Frost’s Descent

Frost’s Descent arrives when the sun reaches a celestial longitude of 210 degrees, which corresponds to around October 23-24 in the Gregorian calendar. The period goes until approximately November 7-8, when the next solar term, Beginning of Winter (立冬 Lìdōng), commences.

While its name might conjure the visual of frost literally falling everywhere, Frost’s Descent actually signifies a sudden drop in temperature and increasingly sharp temperature swings between day and night. Temperatures during this time vary considerably across China’s vast geography. In northern regions, frost may already coat outdoor surfaces each morning, while in southern areas, days are generally temperate with the change most noticeable in cooler evenings.

Generally speaking, as nighttime temperatures plunge, moisture in the air condenses and, on sufficiently cold surfaces, crystallizes. Dew becomes frost. Delicate ice formations appear on grass, leaves, and plants at dawn. By day, the weather can still be mild, with cool winds carrying the last of autumn’s leaves in what feels like an unhurried farewell.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

The 24 Solar Terms: Mythology, Folkways, and Poetry of the Chinese Nature Almanac by James W. Murphy

Solar Terms Playing Cards by VermilionCollection on Etsy.

Twenty-Four Solar Terms Calligraphy Bilingual Flashcards with Simplified Chinese and Mandarin Pinyin by ShuoArtStudio on Etsy.

Twenty-Four Solar Terms Flashcards designed for Mandarin Learners by KongCrafts (Stephen Kong) on Etsy.

Health and Wellness during Frost’s Descent

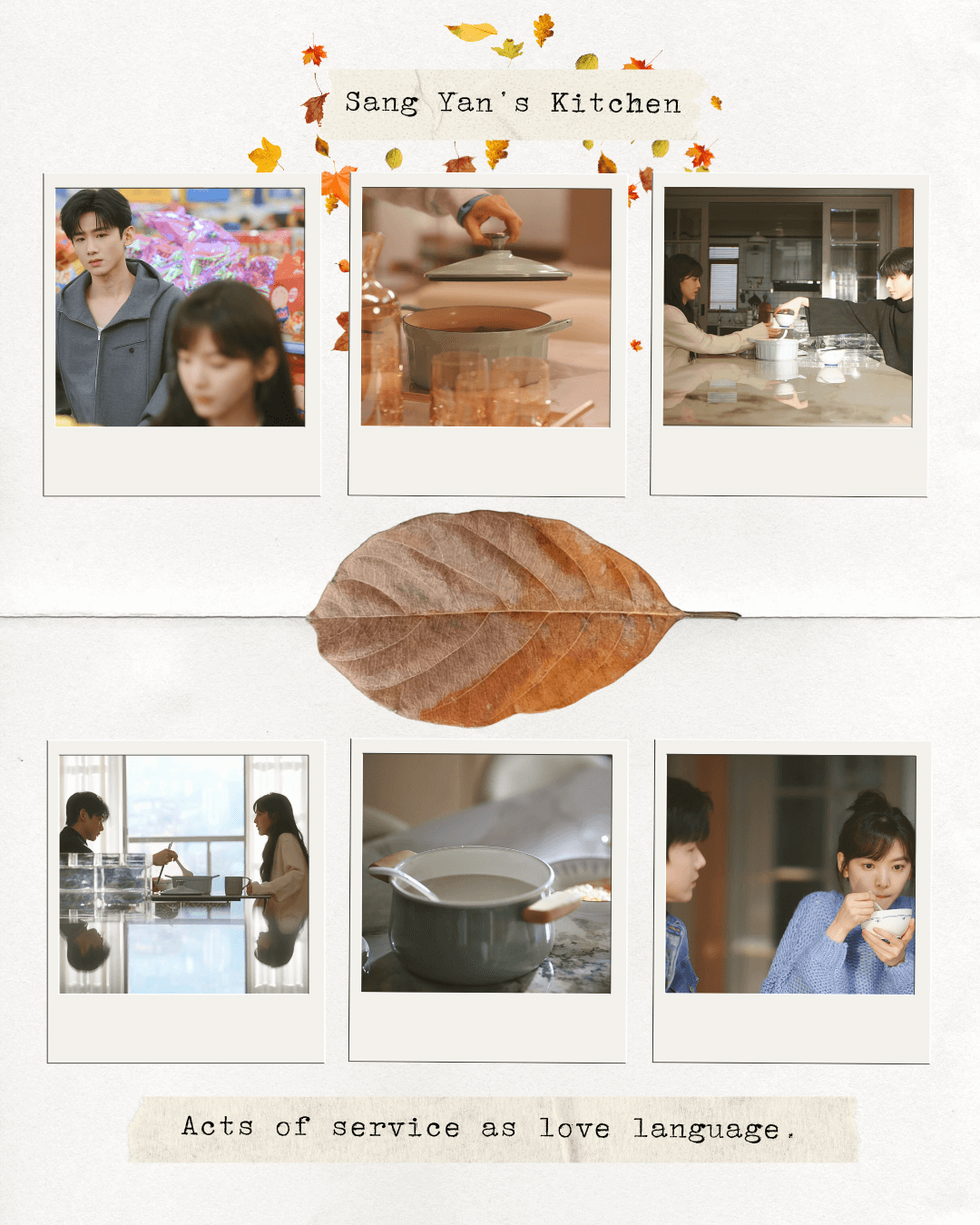

In ‘The First Frost,’ Sang Yan’s defining way of expressing love for Wen Yifan is through acts of service. He stocks up on groceries. He cooks. He makes sure she eats. Bai Jingting plays this not as a grand romantic gesture but by quietly placing warm meals on the table to show how much he cares.

Understanding the cultural associations of this solar term reveals how closely his actions mirror the customs of Frost’s Descent: stocking up, cooking nourishing meals, and preparing for colder days. Even his choice of ingredients aligns with traditional recommendations.

A well-known Chinese folk saying goes: “No amount of nourishment throughout the year compares to nourishing the body during Frost’s Descent” (“一年补透透,不如补霜降” yī nián bǔ tòutòu, bù rú bǔ shuāngjiàng).

According to traditional Chinese medicine and folk wisdom, Frost’s Descent is a crucial period for tending to health. The customs and practices of this season center on fortification: nourishing ingredients and attentiveness to what the body needs ahead of winter.

Physical Wellness

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) emphasizes aligning diet and exercise with the twenty-four solar terms to promote balance within the body and with the surrounding environment. Restorative practices such as tai chi and qigong follow this same principle.

According to TCM, it is important during Frost’s Descent to strengthen the stomach and spleen. As temperatures drop and the body works harder to adapt to colder conditions, digestive function becomes more vulnerable. TCM holds that fortifying these organs early supports overall health and immunity through the months ahead. Additionally, those at risk of cardiovascular issues should be extra cautious during this period, as the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke increases. The elderly are reminded to monitor their blood pressure and cholesterol and to wear suitable clothing for temperature swings between day and night.

The dry air of this season requires everyone's attention. Staying hydrated and moisturizing the skin helps prevent what is known as autumn dryness. Gentle regular exercise, such as tai chi, qigong, or walking, supports the body through this seasonal transition.

Food and Nourishment

The traditional diet in Frost’s Descent centers on foods rich in protein, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. While regional cuisines vary, certain foods feature prominently: persimmons, pears, red dates (Chinese jujubes), chestnuts, radishes, Chinese yams, beef, duck, lamb, and rabbit. In TCM, these foods are prized for nourishing blood and qi (vital energy), strengthening the spleen and stomach, warming the body, and fortifying against cold — qualities that support overall strength and immunity.

Soups, congee, and other warming, easy-to-digest dishes are encouraged during this period to support digestive health. The aim is warmth from the inside out.

What Sang Yan prepares for Wen Yifan aligns remarkably well with these recommendations. He makes congee, gentle on the stomach and deeply warming. He prepares chicken soup with red dates, which tonifies qi and nourishes blood. He serves a warming and protein-rich beef noodle soup. He brings her strawberries and cherries, fruits rich in vitamins and antioxidants. In the language of the solar terms, Sang Yan cares for the person beside him during the time of year when that care matters most.

Persimmon Season

The folk custom of eating persimmons during Frost’s Descent is linked to a Ming Dynasty legend about the dynasty’s founding emperor, Zhu Yuanzhang, also known as the Hongwu Emperor. The story goes that a young Zhu Yuanzhang, of humble origins, arrived at a remote village during Frost’s Descent after running out of provisions. Wandering and starving, he spotted a persimmon tree bearing vivid red fruit. Its persimmons saved him from starvation. Years later, after ascending the throne, he passed through the village again. The persimmon tree was still standing. At once, he dismounted, removed his red robe, draped it over the tree, and proclaimed: “I confer upon you the title ‘Frost-Defying Marquis’ (凌霜侯 Líng Shuāng Hóu).”

Today, fresh ripe persimmons and dried persimmon cakes are enjoyed in China during this period. In the northeast, frozen persimmons are a popular icy treat.

Frost-Sweetened Flavors

The cold snaps around Frost’s Descent create a natural phenomenon known as ‘frost-hit vegetables’ (霜打菜 shuāng dǎ cài). Cold-hardy plants, such as spinach and carrots, convert some of their starches into sugars to resist freezing, making them taste noticeably sweeter after the first frost.

This is a fitting metaphor for Wen Yifan’s journey. Like these plants that develop resilience to endure the cold, she emerges from hardship stronger and more herself. And now, she can look ahead to a sweeter future.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Jadeite Leaf Charm for Bracelet or Necklace by JadeUnique (Henry Lee) on Etsy.

Handcrafted Persimmon Chinese Ceramic Teapot Set with Green and Red Glaze by WishingToken (Wen) on Etsy.

Persimmon Chinese Ceramic Tea Set from TheHomeEditry (Aria) on Etsy.

Chinese Persimmon and Botanical Decal Nail Stickers from PhamNails (Phuong Pham) on Etsy.

Customs and Activities for Frost’s Descent

The solar terms offer a way of living in tune with the environment. Along with food customs, many other activities and rituals are still observed today. In recent years, there has been renewed cultural interest in reconnecting with seasonal awareness in an increasingly urbanized society.

Beyond sharing comfort meals with loved ones, there are many traditional activities to enjoy and celebrate this period. While customs vary across regions and ethnic groups, these practices remain well-observed and easily adaptable to modern life.

Walking Among Autumn Leaves

This is the perfect time to walk in nature and appreciate the red and orange hues of late autumn. Maple leaves, which deepen in color after frost, create vivid landscapes. As the Tang dynasty poet Du Mu famously wrote in his poem ‘Mountain Journey’ (《山行》Shān Xíng): “Frost-touched leaves are redder than February flowers” (“霜叶红于二月花” shuāng yè hóng yú èr yuè huā).

Hiking and Sightseeing

Hiking to a high vantage point, or, like Wen Yifan, stepping onto a balcony and looking out over a vista, can lift the spirit and calm the mind. Frost’s Descent is traditionally associated with a melancholy marked by introspection and reflection on what has passed, paired with preparation for what lies ahead.

Admiring Chrysanthemums

Frost’s Descent occurs around the peak blooming season for chrysanthemums, celebrated in Chinese culture as a symbol of vitality, reflecting their ability to flourish in cold weather. Chrysanthemum festivals and garden exhibitions around this time are held in regions across China, including at Chongqing’s Nanshan Botanical Garden, Nanjing’s Xuanwu Lake, and Shenyang’s Beiling Park. People also drink chrysanthemum wine or tea to celebrate the blooming season.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Handmade Chrysanthemum Petal Clay Teapot Set by WishingToken (Wen) on Etsy.

Frosted Gray Crackle Glaze Gaiwan Tea Set with Saucer by PrideForHong (Longfan) on Etsy.

The Color Palette of Frost’s Descent

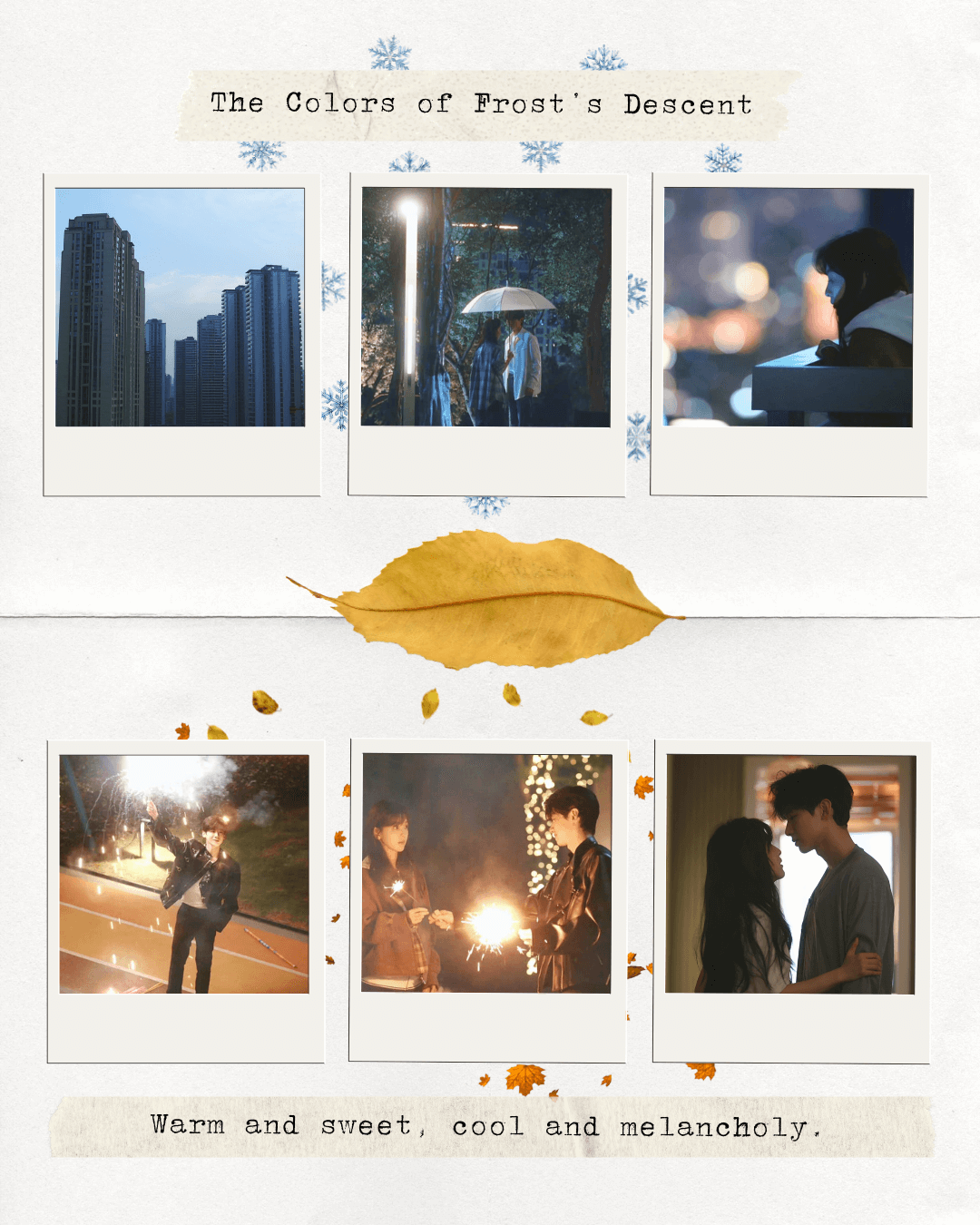

Frost’s Descent embodies contrasting qualities: warm and sweet, yet cool and melancholy. Golden-orange autumn colors glow against icy blues. Sunlight and the last of the autumn leaves permeate through frost, creating a visual language of coexistence between warmth and cold.

Wen Yifan’s name mirrors this duality — Wen for warmth, and Shuangjiang for Frost’s Descent. She is a woman impacted by chilling, cruel events in her formative years, yet her fundamental nature remains warm and kind.

‘The First Frost’ intentionally reflects the palette of this solar term. The drama’s cinematography blends and shifts between warm amber and cool blue tones, mirroring Frost Descent’s duality. When Sang Yan re-enters Wen Yifan's life, he brings warmth into her carefully guarded, frost-touched world. The drama conveys this visually through lighting, color grading, and the composition of each scene.

Frost in Classical Poetry

The twenty-four solar terms have inspired Chinese classical poetry for centuries. Frost, in particular, has become one of the most evocative images of this poetic tradition, associated with the melancholy of autumn’s fleeting beauty.

In ‘A Night Mooring by Maple Bridge’ (《枫桥夜泊》Fēng Qiáo Yè Bó), Tang dynasty poet Zhang Ji writes:

Moon sets, crows cry, frost fills the sky;

River maples and fishing boat lights keep company with sleepless sorrow.

Beyond the walls of Gusu City stands Hanshan Temple.

The sound of the midnight bell reaches the traveler’s boat.

月落乌啼霜满天,江枫渔火对愁眠。

姑苏城外寒山寺,夜半钟声到客船。

yuè luò wū tí shuāng mǎn tiān, jiāng fēng yú huǒ duì chóu mián.

gūsū chéng wài hánshān sì, yè bàn zhōng shēng dào kè chuán.

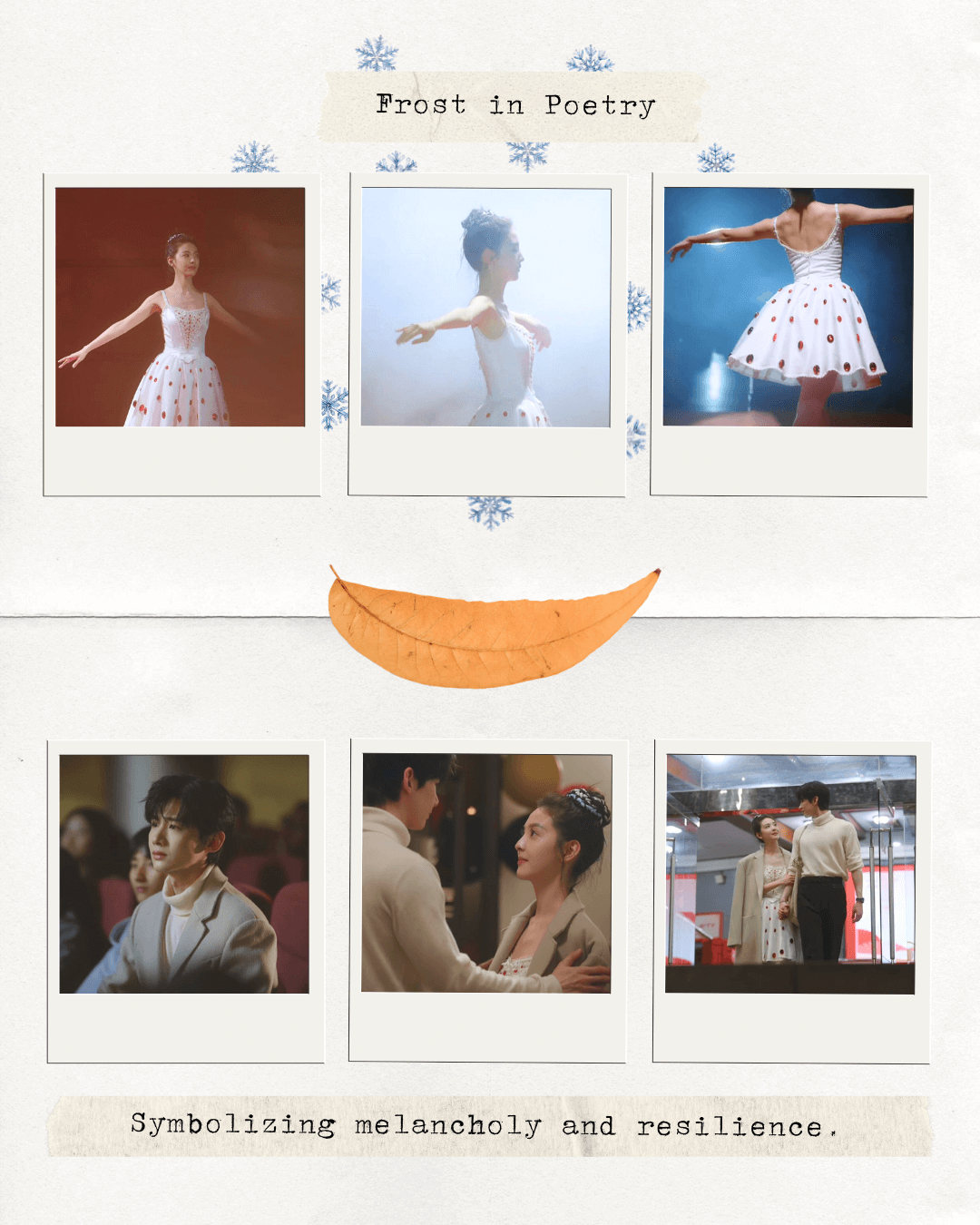

Yet, frost in Chinese poetry also symbolizes resilience. In ’To Liu Jingwen’ (《赠刘景文》Zèng Liú Jǐngwén), Song dynasty poet Su Shi reflects:

The lotus is spent, no more rain canopies held high.

The chrysanthemum fades, yet frost-defying branches remain.

The finest scene of the year, you must remember:

Right when oranges are yellow and mandarins are green.

荷尽已无擎雨盖,菊残犹有傲霜枝。

一年好景君须记,正是橙黄橘绿时。

hé jìn yǐ wú qíng yǔ gài, jú cán yóu yǒu ào shuāng zhī.

yì nián hǎo jǐng jūn xū jì, zhèng shì chéng huáng jú lǜ shí.

In traditional Chinese culture, these “frost-defying branches” represent steadfast character and integrity preserved under harsh conditions. The capacity to endure frost has become a metaphor for nobility of spirit, for standing firm when the world turns cold.

While ‘The First Frost’ does not explicitly reference these classical poems, the drama inhabits their emotional landscape. Wen Shuangjiang lives and breathes the poetic symbolism of frost with its melancholy and resilience. She is a woman acquainted with loss and cruelty who, like those enduring branches, remains standing.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

300 Tang Poems, translated by Xu Yuanchong, bilingual Chinese-English edition.

First Frost Pattern Embroidered Tulle Lace, handpicked by EmeraldErinInc on Etsy.

The Language of Care

Guided by the wisdom of Frost’s Descent, ‘The First Frost’ tells a story of healing through the quiet accumulation of care and attentiveness.

Both Wen Yifan and Sang Yan gradually heal and grow on their own and with each other’s support. Wen Yifan’s journey reflects an understanding shared by traditional wisdom and modern insight — that it is possible to begin healing through relationships built on trust and consistency. Sang Yan, meanwhile, learns to let go of his wounded pride from their school days. The drama shows healing through the language of ‘coaxing,’ which requires patience and compassion from others and the harder task of extending that same compassion inward.

Frost’s Descent reminds us that showing up, day after day, with nourishing meals and thoughtful rituals, is itself a profound act of love. The drama speaks this language fluently, revealing love demonstrated through action and rooted in centuries of seasonal wisdom. Together, they offer a guide we have explored here: that even in a harsh world, small acts of care help us find our feet and regain our balance.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Hand-woven Chinese Lucky Knot Bracelets for Couples (can also buy individually) by LIUJIXUAN on Etsy.