When monsters can assume human form, think and reason like us, love and yearn for belonging — what does it mean to be human?

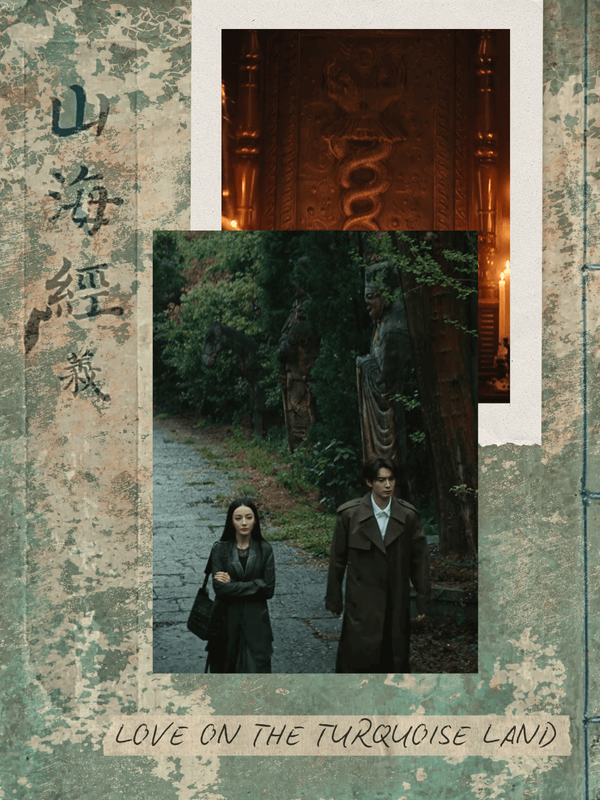

Adapted from Weiyu’s novel of the same name, Love on the Turquoise Land follows sculptor Nie Jiuluo (Dilraba Dilmurat) and corporate heir Yan Tuo (Chen Xingxu) as they investigate the mystery behind underground creatures known as Earth Fiends (地枭 dìxiāo). A secret order called the Nanshan Hunters has battled these creatures for centuries to protect humankind. Nie Jiuluo is one such hunter, though she pursues sculpture as her chosen vocation, embodying both warrior and artist.

As the story unfolds, the boundaries between human and monster, protector and predator, begin to blur in unsettling ways. At times, the drama positions us to sympathize with Earth Fiends who demonstrate fierce loyalty, while some human characters prove more unlikable and self-centered. This subverts the hero-villain dichotomy that has traditionally shaped both storytelling conventions and audience expectations.

Central to the drama’s worldview is the imagery of the gods Nüwa and Fuxi with human faces atop serpent bodies, their tails intertwined as kin and complementary forces embodying both human and beast.

Drawing from Chinese mythology, historical art, and traditional culture, ‘Love on the Turquoise Land’ explores what it means to be human through acts of creativity, beauty, and ritual, while traversing the permeable boundary between human and monster.

Nüwa

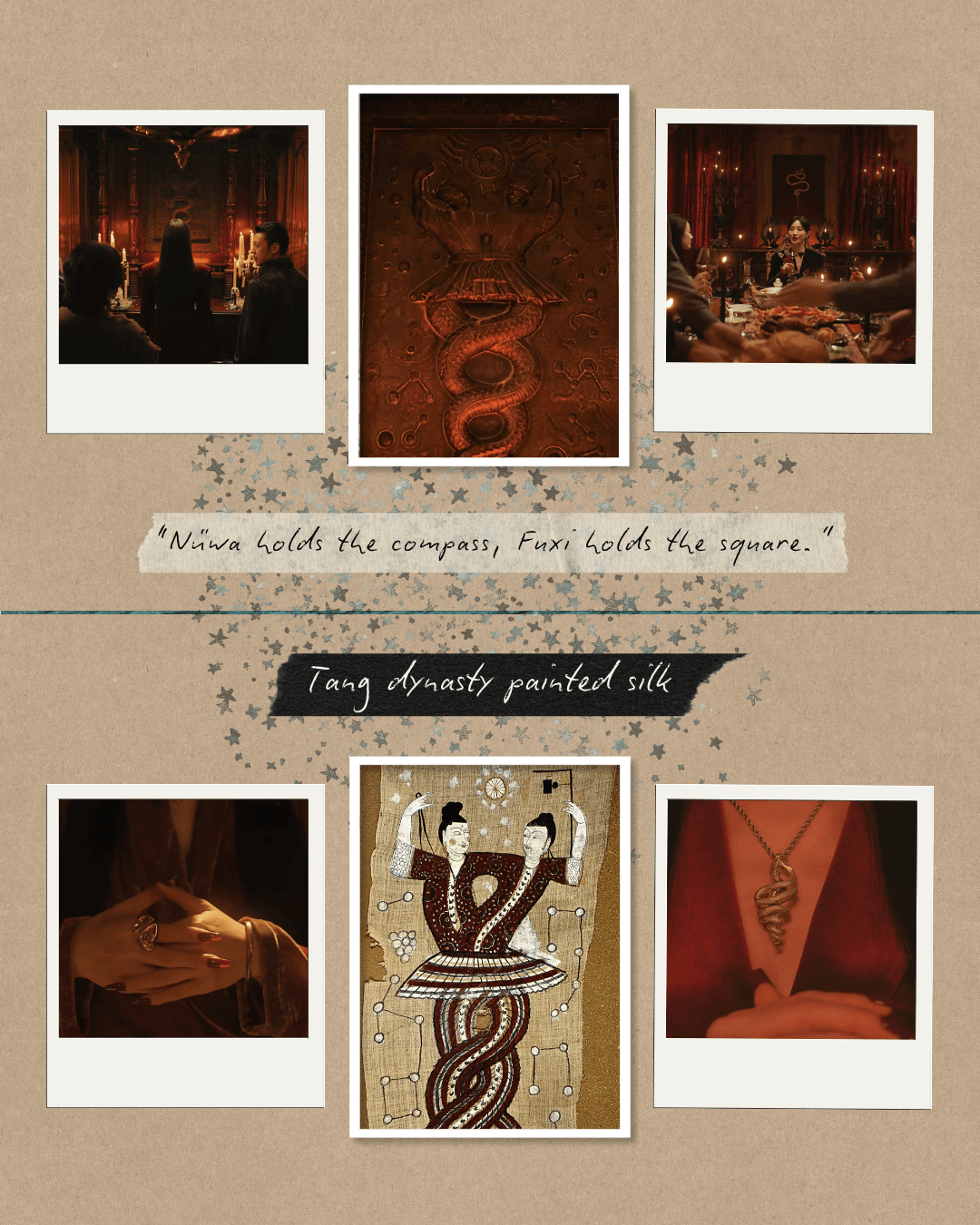

In ‘Love on the Turquoise Land,’ the Earth Fiends, led by Lin Xirou (Zhang Li), appear to worship Nüwa, performing rites before a relief depicting the goddess paired with Fuxi, her brother and husband, their serpent tails intertwined.

Nüwa is a creation goddess and one of the Three Sovereigns of Chinese mythology, credited with creating humanity and all living things. She is most famous for molding humans from yellow clay, melting five-colored stones to repair the heavens, and inventing musical instruments, including the xun ocarina.

Wang Yi’s annotated commentary to ‘Heavenly Questions’ (《天问》Tiān Wèn) in the ‘Songs of Chu: Chapters and Verses’ (《楚辞章句》Chǔcí Zhāngjù) describes Nüwa as having “a human head and serpent body, capable of seventy transformations in a single day,” speaking to both her power of transformation and her ability to generate countless new forms of life. The Earth Fiends’ devotion makes perfect sense: Nüwa embodies the very metamorphosis they have achieved.

Fuxi, her counterpart, is another of the Three Sovereigns, revered as a culture hero who taught humanity essential skills and created the Eight Trigrams (八卦 bāguà) that form the basis of the I Ching. As Lin Xirou states: “Nüwa holds the compass, Fuxi holds the square. Without rules, nothing takes proper shape” (“女娲持规,伏羲执矩。没有规矩,不成方圆。” Nǚwā chí guī, Fúxī zhí jǔ. Méiyǒu guījǔ, bù chéng fāngyuán).

In Han Dynasty funerary art and Tang Dynasty paintings, these instruments often appear alongside the gods: Nüwa holding a compass and Fuxi a carpenter’s square, set amid suns, moons, and stars. Together, they represent the foundational forces of Chinese cosmology, creation and transformation, married with order and civilization.

The intertwined serpents become visual evidence that the Earth Fiends use to legitimize their existence and prove that humans and fiends are two halves of a cosmic whole born from the same divine source. Their intertwined tails also suggest a darker meaning: just as Nüwa and Fuxi are inextricably connected, Earth Fiends remain bound to humans, needing to leech off human life to maintain their human form.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Nüwa Mends the Sky Chinese Mythology Fantasy Art Diorama Storybook by PocketMythsStudio on Etsy.

Nüwa and Fuxi Intertwined Silver Glitter Ornament by MojoFascination on Etsy.

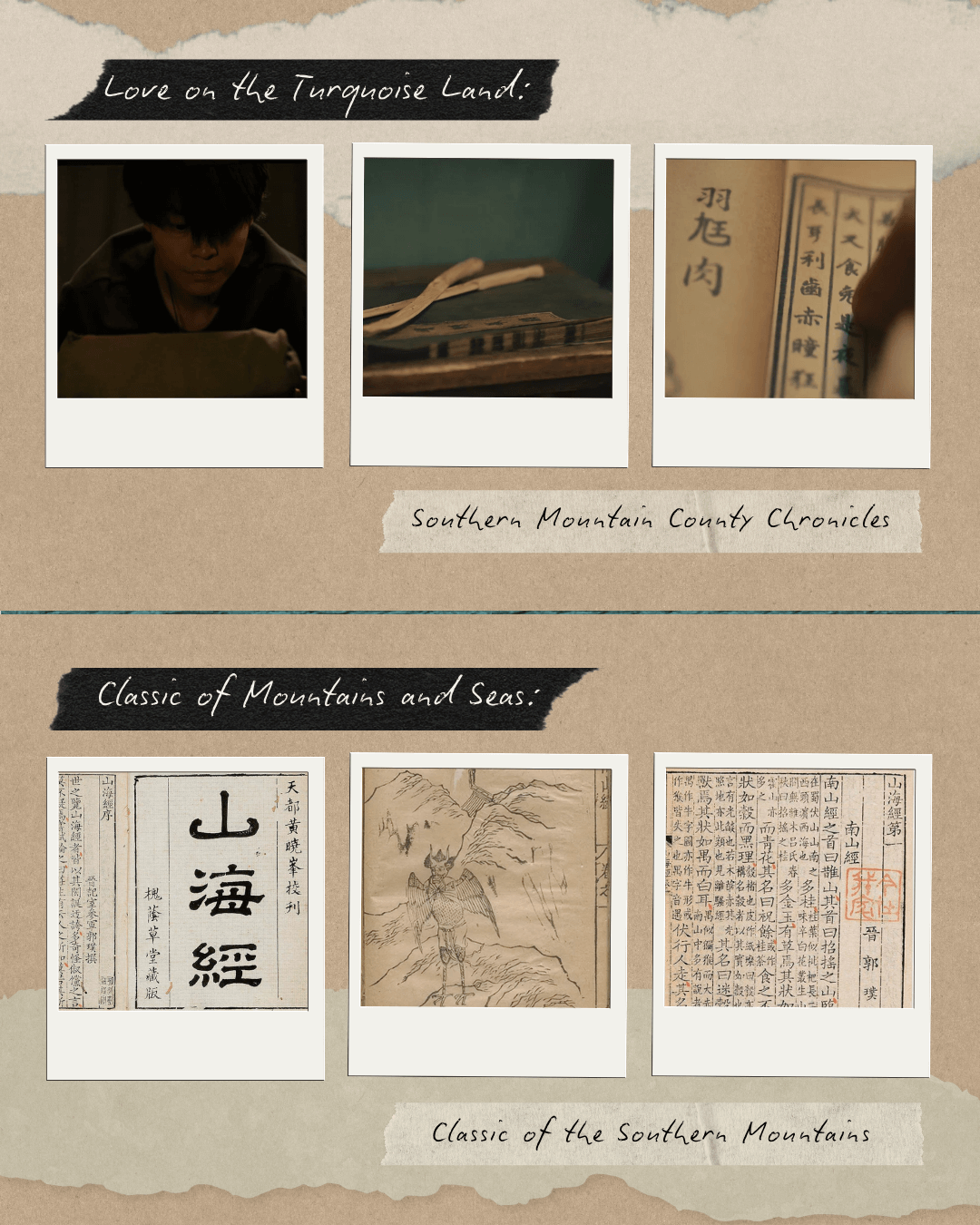

‘Classic of Mountains and Seas’

The Classic of Mountains and Seas (《山海经》Shānhǎi Jīng) is a compendium of entries on natural and spiritual worlds, compiled by multiple authors between the Warring States period and the Han dynasty. Its eighteen surviving sections, also described as scrolls or volumes, document many hundreds of geographical features, deities, spirits, and fantastical creatures, organized by region and realm.

From its contents, readers across generations have extracted what we now recognize as well-known Chinese myths, insights into cosmology and philosophy, knowledge of ancient peoples, shamanistic practices, and medicinal lore. Over time, this collection has achieved legendary status, serving as a source of inspiration for scholarship, art, and storytelling, cultivating fresh perspectives on the beings and worlds it describes.

The text establishes a worldview in which the natural and supernatural exist on a continuum, where the consumption of certain substances grants power or transformation, and where geography itself holds spiritual power — concepts that ‘Love on the Turquoise Land’ directly incorporates into its narrative. The drama draws from this compendium both thematically and stylistically, creating fictional entries that mirror the text’s language and format.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Fantastic Creatures of the Mountains and Seas: A Chinese Classic Illustrated Book by Jiankun Sun, illustrations by Siyu Chen.

Hardcover with illustrations | eBook

Southern Mountains

The ‘Classic of the Southern Mountains’ (《南山经》Nánshān Jīng) is the opening section of the ‘Classic of Mountains and Seas,’ the first of the compendium’s five Mountain Classics.

This section records three major mountain systems encompassing forty mountains, large and small, spanning 16,380 li (approximately 8,000 kilometers). It describes natural resources such as gold and jade, mythical creatures, rare plants, and ritual practices dedicated to mountain gods. Mount Zhaoyao yields the divine herb zhuyu (祝余 zhùyú), and eating it prevents hunger. On Mount Qingqiu dwells the nine-tailed fox (九尾狐 jiǔwěihú) and the guanguan (灌灌 guànguàn), a bird that protects against bewitchment when worn. Mount Danxue is home to the phoenix (凤凰 fènghuáng, also written as 凤皇), and when it appears, it heralds peace under heaven.

Yet the mountains also harbor man-eating beasts and creatures that portend disaster. In the waters near Mount Luwu dwells gudiao (蛊雕 gǔdiāo), a beast that resembles a bird of prey with horns. Its cry sounds like an infant’s wail, and it devours people. On Mount Changyou lives a beast called changyou (长右 chángyòu), and whenever it is seen, great floods will strike the land.

The drama situates its secret hunter society within this mythic landscape, naming the Nanshan Hunters, which means ‘Southern Mountain’ Hunters, after the ‘Classic of the Southern Mountains’ (Nanshan Jing). Just as the Classic catalogues strange beasts dwelling in mountains and waters — some benevolent, some monstrous, some capable of granting power — the drama imagines the Southern Mountains as a space where humans and creatures have coexisted and clashed since antiquity. The hunters who patrol this terrain inherit a duty to protect humans in a land where the boundary between the ordinary and the supernatural has always been porous.

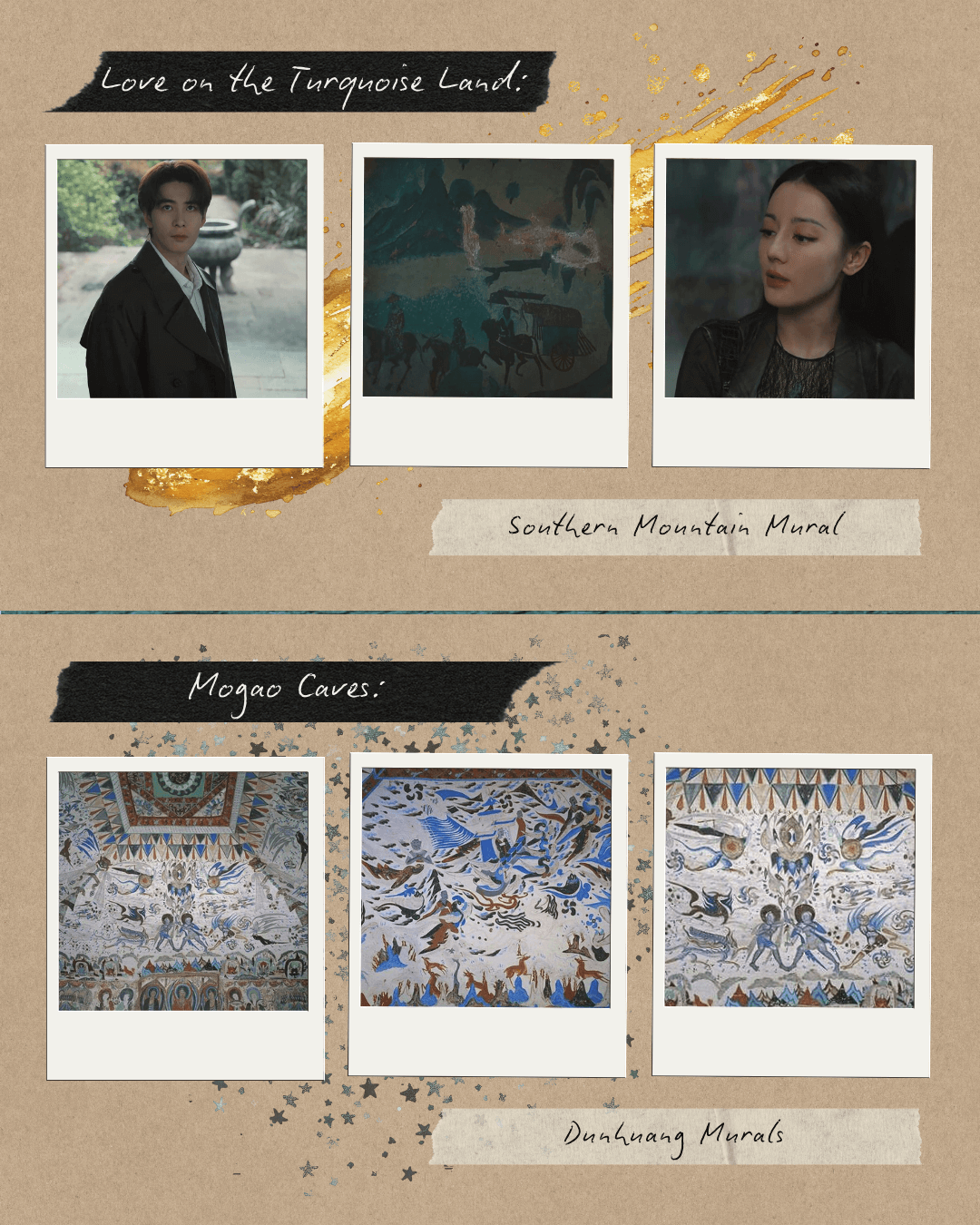

Dunhuang Murals

In ‘Love on the Turquoise Land,’ Nie Jiuluo shows Yan Tuo the origin story of the Nanshan Hunters and Earth Fiends, painted on a temple mural.

“The mural used to introduce the worldbuilding was inspired by Dunhuang cave murals,” explains the drama’s director, Tian Li.

The Dunhuang cave murals are found in the Mogao Caves (莫高窟 Mògāo Kū) in Gansu Province. From the Northern Dynasties period onwards, flourishing notably during the Tang dynasty with ample patronage, and continuing through the Yuan dynasty, cave excavation and painting spanned nearly a millennium. Because the cliff rock at Dunhuang was both too hard and too fragile for carving, artisans applied layers of mud plaster to cave walls and ceilings, coated them with whitewash, and painted directly onto the smoothed surface.

The murals are renowned for their exquisite detail, painted in vivid mineral pigments: brilliant blues and greens, cinnabar reds, and gold. Alongside Buddhist themes and scriptural narratives, some murals feature Chinese mythological figures, including Nüwa, Fuxi, and the Queen Mother of the West, connecting Buddhist tradition with Chinese cosmology.

The drama’s mural draws on Dunhuang’s visual style, from the flowing lines to the color scheme and mythological imagery used to depict the primordial story of humans and Earth Fiends.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Dunhuang Mural Coloring Book by Wu Xiaohui, a relaxing mindfulness activity with 24 carefully selected motifs from cave paintings.

Dunhuang Murals Linen Fabric by PoppyLollipop on Etsy.

Dunhuang Murals Tea Tray by AntiqueArt1 on Etsy.

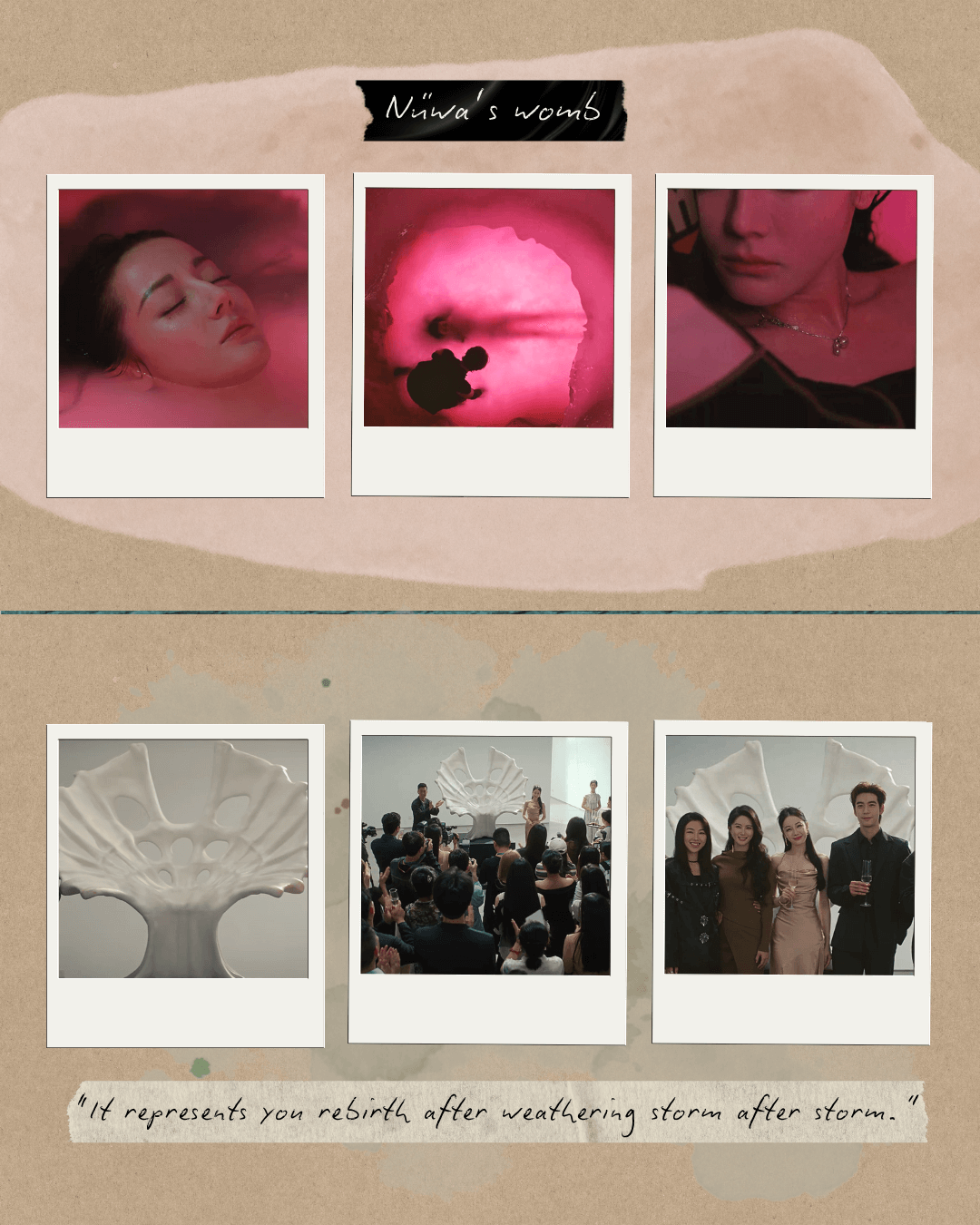

Nüwa’s Womb

The drama creates its own fictional entry in the style of the ‘Classic of Mountains and Seas’ through its ‘Southern Mountain County Chronicles’ (《南山县志》Nánshān Xiàn Zhì):

Yuwang meat often mingles with the Turquoise Land. Its purest form resembles jellyfish, luminous as jade. It feels fatty to the touch, and at night it gives off a fluorescent glow.

Long ago, a Nanshan Hunter surnamed Tu found this substance. His hounds ate it and then preyed on rabbits. They died suddenly that day. Their corpses were buried in the Turquoise Land and, as they decayed, they spawned strange beasts. They had long ears, sharp teeth, red eyes, and mad howls. They resembled hounds and rabbits, yet they were neither hound nor rabbit …

Yuwang meat regenerates endlessly and returns to its original form. Eating it strengthens vitality, granting longevity that may rival that of the turtle and the crane. It is not fit for those who remain in the mortal world. One should withdraw into the mountains and forests and cultivate in seclusion, becoming an immortal.

The emperor, seeking the way to eternal life, sent officials to sail east in search of an elixir. The Qin troops entered the Southern Mountain for this very reason.

“So yuwang meat can merge two species,” Nanshan Hunter Xing Shen (Dong Chang) observes.

The drama’s Twilight Chasm — the liminal zone where Earth Fiends and Nanshan Hunters battle and transform — features visceral imagery of organs and internal structures giving rise to life. This visual motif is inspired by the ‘Classic of Mountains and Seas,’ which mentions “ten gods known as the intestines of Nüwa” (“有神十人,名曰女娲之肠” yǒu shén shí rén, míng yuē nǚwā zhī cháng). Eastern Jin scholar Guo Pu interpreted this in his commentary as Nüwa’s womb, suggesting that the goddess’s own body and flesh birthed new gods and forms of life.

In the drama, yuwang meat (羽汪肉 yǔwāng ròu) is the substance that explains how Earth Fiends came to exist and then how they can assume human form after consuming it. The name is intended as a phonetic pun: yuwang (羽汪 yǔwāng) sounds similar to ‘desire’ (欲望 yùwàng), embodying the Earth Fiends’ yearning for humanity. In the original novel, the substance is called Nüwa meat (女娲肉 nǚwā ròu), a direct reference to the creator goddess.

Nie Jiuluo undergoes a kind of rebirth in the Twilight Chasm. Later, she creates a sculpture that resembles a pelvis: the skeletal structure that supports the womb. Her sculpture offers a reflection on origins, transformation, and maternal connection.

Actress Dilraba Dilmurat describes the significance of Nie Jiuluo’s sculpture:

It isn’t just a sculpture made with painstaking effort. It represents your rebirth after weathering storm after storm, peeling off the fear and disguises of the past, and finally embracing your truest self.

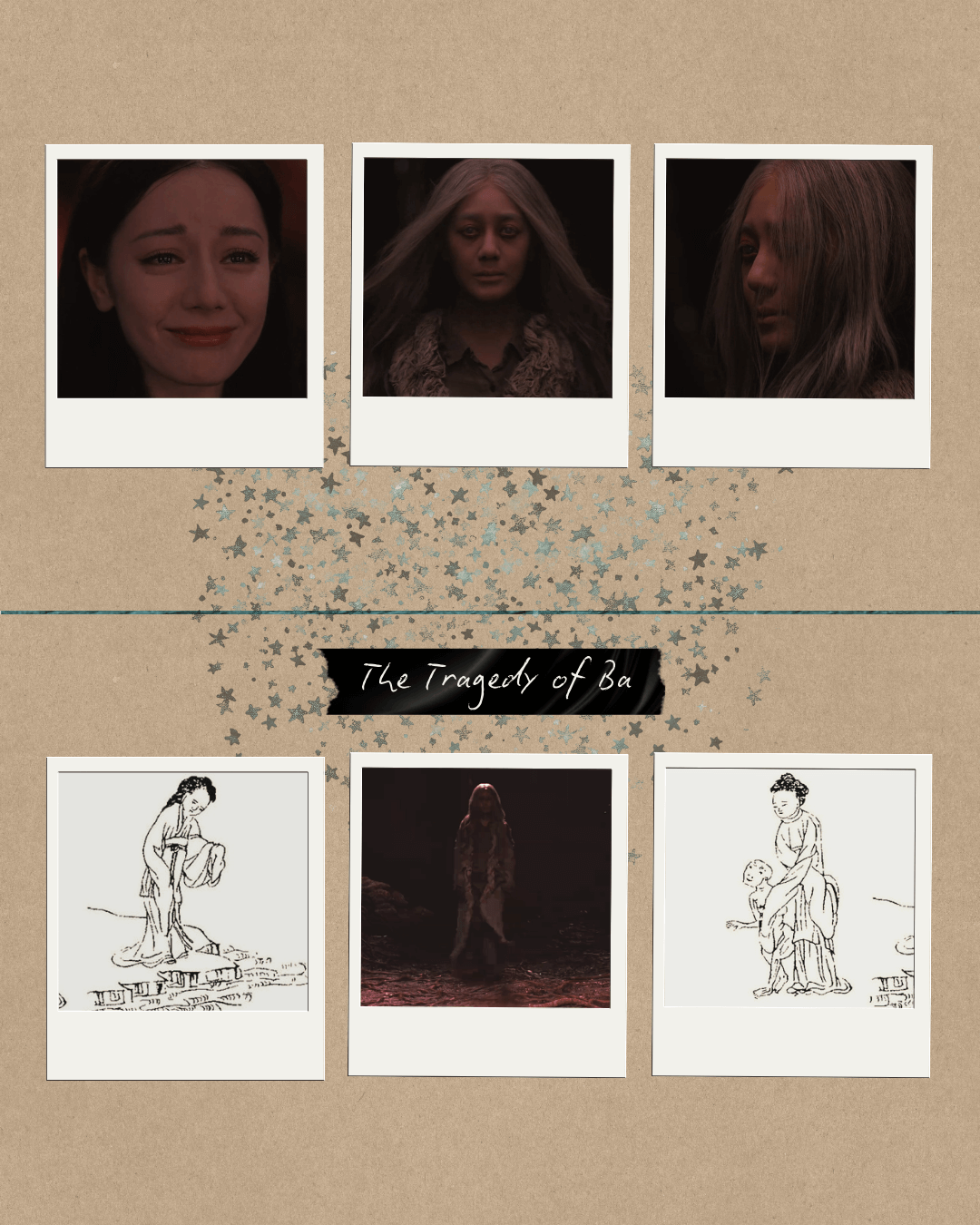

Ba

Nie Jiuluo's mother, Pei Ke (Nie Chuyi), and several other Nanshan Hunters became Earth Demons (地魃 dìbá) in the Twilight Chasm after fighting Earth Fiends. Transformed into monsters, they lock themselves underground and can never return home. This draws on one of Chinese mythology’s most tragic figures: Nüba (女魃 nǚbá), or simply Ba, a deity who sacrifices herself to end a storm and, as a consequence, becomes a demon, unable to return to heaven.

In the ‘Classic of the Southern Mountains,’ Ba descends as a heavenly maiden summoned by the Yellow Emperor to halt the violent tempest brought on by Chiyou. As a drought deity, she quells the storm but exhausts her powers in the process. After the battle ends, she cannot return to heaven, and wherever she wanders, drought follows, transforming her from heroine into a demon of calamity.

‘Love on the Turquoise Land’ makes Ba a symbol of warriors consumed by the cosmic imbalance they battle. The Nanshan Hunters, who became Earth Demons after infection, echo her tragedy. Neither alive nor dead, neither human nor fiend, they confine themselves in the depths of the chasm. The drama suggests that heroism has costs beyond death. Some guardians, like the Nanshan Hunters, are lost because the world they defended no longer has a place for them. In every battle, we risk becoming the thing we fight against.

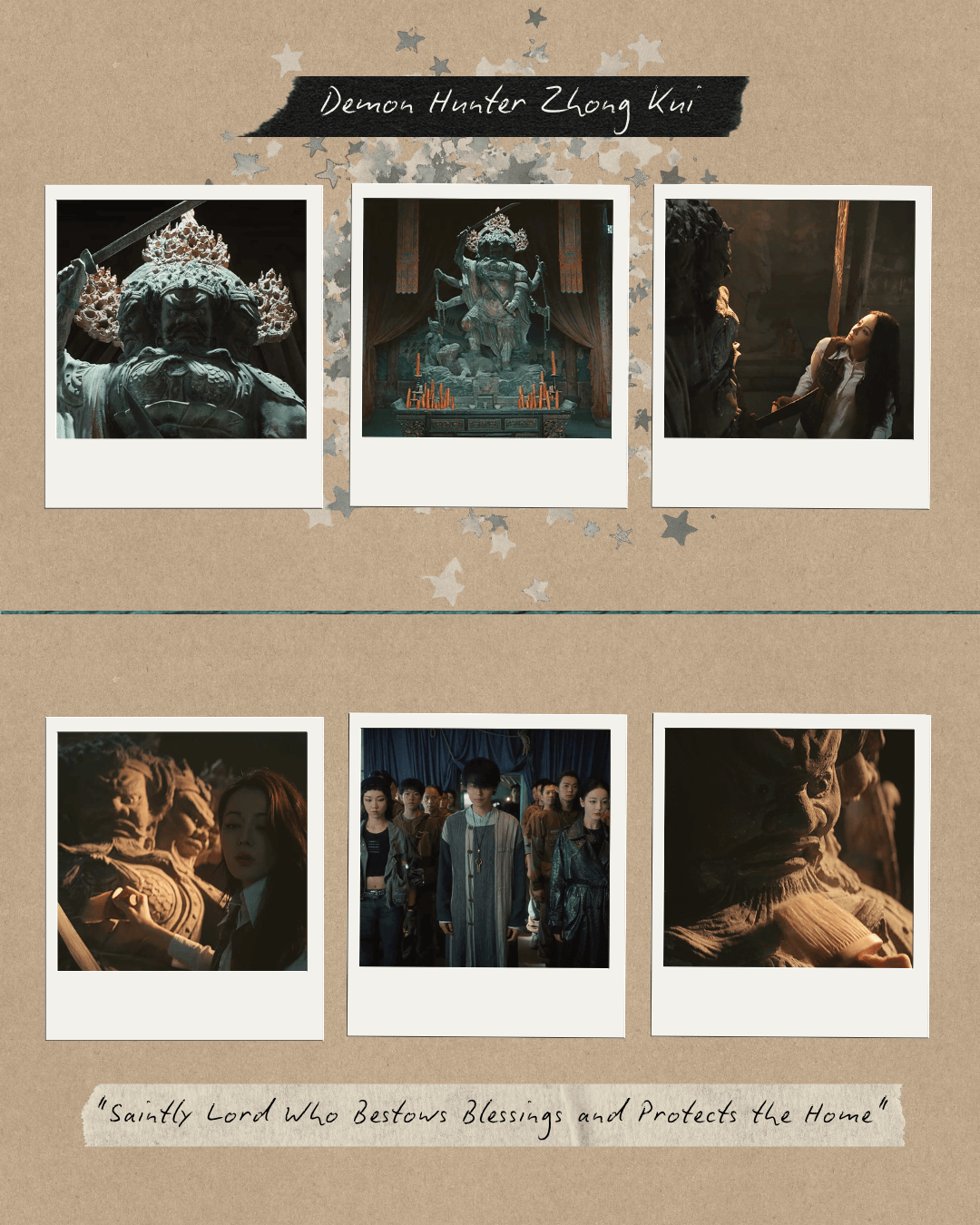

Zhong Kui

When Nie Jiuluo visits a temple seeking inspiration for her sculptures, she encounters a statue of the demon-vanquishing deity Zhong Kui (钟馗 Zhōng Kuí).

“Zhong Kui catches ghosts, right?” remarks the tour guide, Sun Zhou (Ding Wenbo).

“Zhong Kui has three heads and six arms?” Nie Jiuluo retorts.

Not in traditional iconography — but in the drama, these three heads represent the Nanshan Hunters’ three clans.

The Blades, headed by ‘Mad Blade’ Nie Jiuluo, specialize in combat, eliminating Earth Fiends with a single strike.

The Hounds, headed by ‘Rabid Hound’ Xing Shen, have an acute sense of smell and can track Earth Fiends by scent.

The Whips, headed by ‘Ghost Whip’ Yu Rong (Cherry Ngan), control and condition Earth Fiends using whip sounds for dominance.

Together, they form the Nanshan Hunters, led by their head coach and father figure, Jiang Baichuan (Tian Xiaojie).

The drama’s three-headed sculpture appears to be stepping on an Earth Fiend, positioning the Nanshan Hunters as demon-vanquishing protectors in Zhong Kui’s image.

Historical texts claim that Zhong Kui, like the Nanshan Hunters, was human before being venerated as a guardian deity. According to the ‘Brief Biography of Zhong Kui’ (《钟馗传略》Zhōng Kuí Zhuànlüè), he was a scholar from Zhongnan in Yongzhou who mastered both civil and martial arts. Despite his competence, his frightening appearance — leopard-shaped head, iron-like face, and coiling whiskers — led to him being denied the top scholar honor, even though he placed first among candidates in the imperial examinations. He protested the injustice and died, striking a palace pillar in fury. Later, Zhong Kui appeared in Emperor Xuanzong of Tang’s dream, fending off demons. Upon waking, the emperor found himself cured of his longstanding illness. In gratitude, he honored Zhong Kui posthumously as ‘Saintly Lord Who Bestows Blessings and Protects the Home’ (赐福镇宅圣君 Cìfú Zhènzhái Shèngjūn) and ordered his image to be displayed throughout the realm to watch over households and dispel evil spirits.

Like Zhong Kui, the Nanshan Hunters are demon vanquishers who stand at the boundary between worlds, defending humanity even as they become something other than human in the fight.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Zhong Kui Sword Pendant Wood Amulet by FiveThundersXuanZhen on Etsy.

Zhong Kui Carved Black Obsidian Pendant by flowspring (Yongfeng Li) on Etsy.

Zhong Kui Jujube Wood Guardian Pendant by FiveThundersXuanZhen on Etsy.

Handcarved Zhong Kui Ring by youerda (You Erda) on Etsy.

Zhong Kui Copper Gilt Carved Statue by kaigugu on Etsy.

Historical Stone Sculptures

Buddhist Sculptures

“The sculpture representing the Nanshan Hunters was modeled on traditional Chinese Buddhist statues, from facial features with kailian to posture and bodily proportions,” says Director Tian Li.

The practice of kailian (开脸 kāiliǎn) refers to the highly skilled and spiritually significant process of sculpting or painting a statue’s facial features — the final stage in creating Buddhist or deity figures.

Like Nie Jiuluo, traditional craftspeople would make special trips to temples to study the works of earlier masters, absorbing techniques and interpretations before working to capture the particular divine presence and spiritual character they sought to express, often crafting uncannily lifelike features that convey both sacredness and humanity.

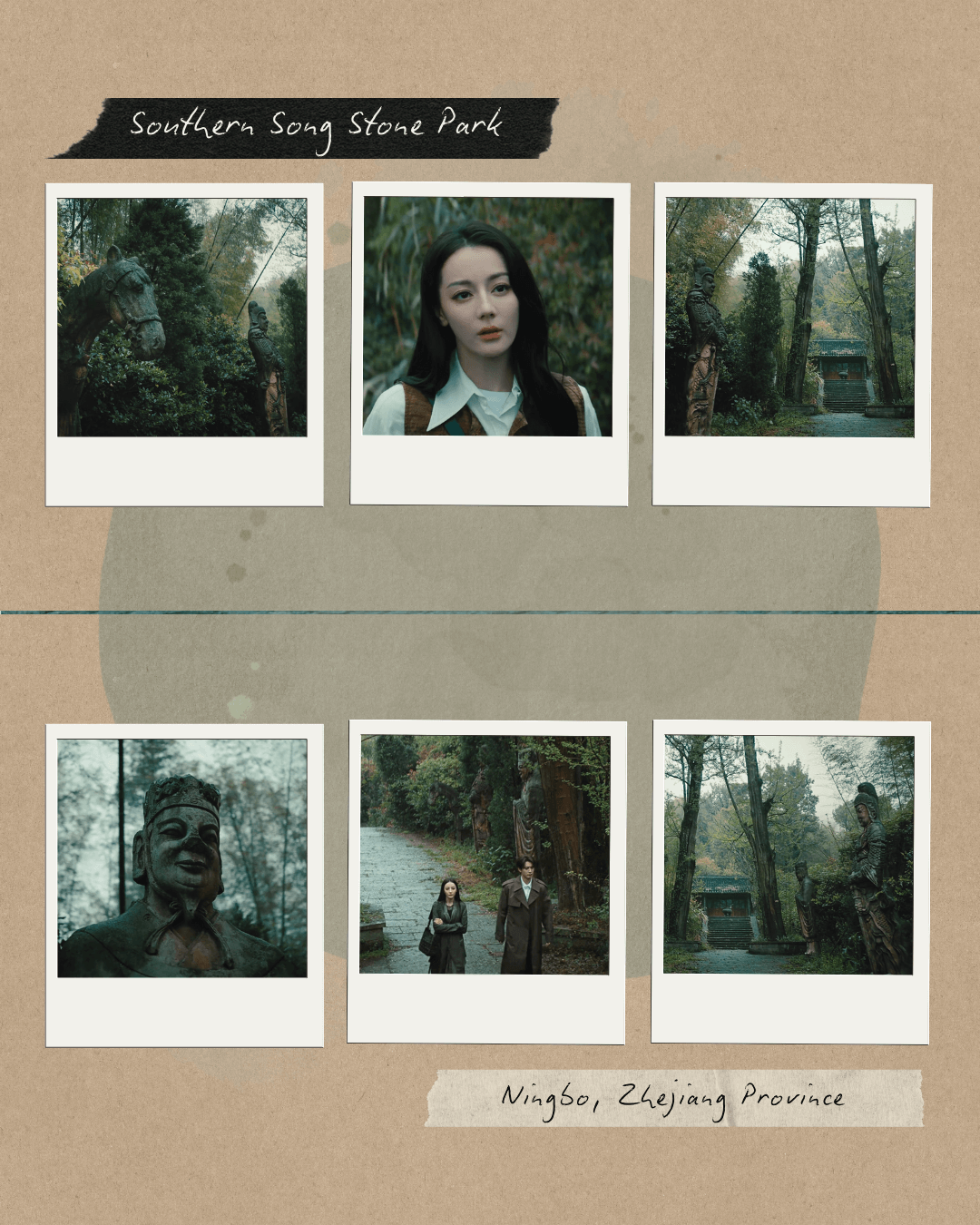

Song Dynasty Stone Sculptures

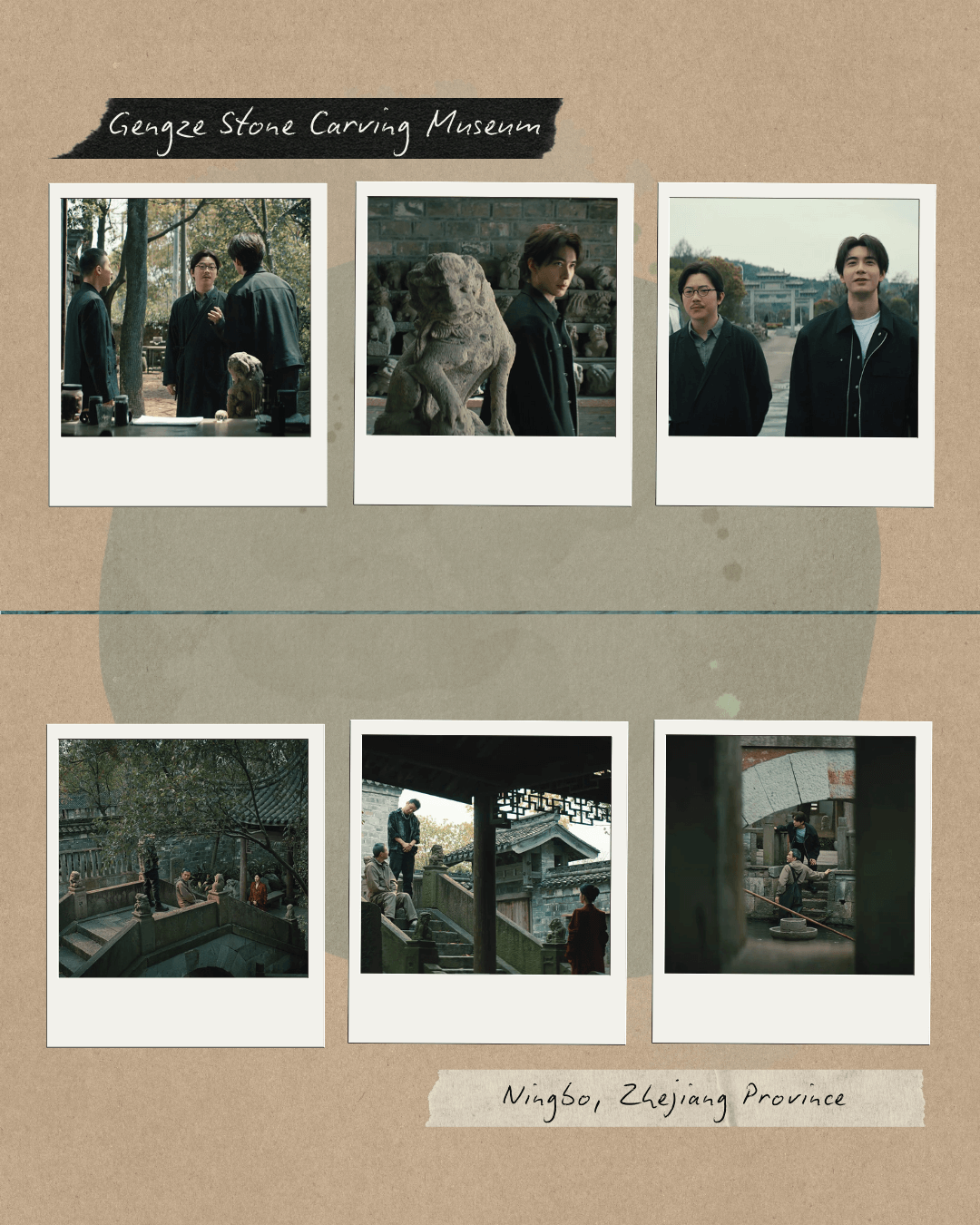

This field trip scene was filmed at the Southern Song Stone Park in Ningbo.

"The filming location for the Zhenjun Temple is home to the largest surviving collection of Southern Song dynasty spirit-way carvings in the world,” says the drama’s Executive Producer, Chang Ben.

During the Southern Song era, officials of the second rank and above could have ceremonial stone figures placed along the spirit way (神道 shéndào) of their tombs after death. Since the Shi family produced three grand chancellors, four generations of princes, five ministers, and seventy-two jinshi (进士 jìnshì), the highest degree in the imperial examination system, they left behind the most prominent examples of spirit-way carvings. Their tombs feature larger-than-life stone sculptures of tigers, horses, sheep, civil officials, and military generals — standing 1.8 meters to over 3 meters tall — carved with meticulous detail.

These stone figures anchor the drama’s worldbuilding in tangible historical art, grounding its mythological narrative in centuries of craftsmanship. In the late Southern Song, four Chinese stonemasons from Ningbo traveled to Japan to participate in the reconstruction of Tōdai-ji monastery in Nara, which points to how these stone-carving techniques spread.

Stone Garden

The Rare Stone Garden in the drama was filmed at the Gengze Stone Carving Museum (耕泽石刻博物馆 Gēngzé Shíkè Bówùguǎn) in Ningbo. At this location, Earth Fiends detain Nanshan Hunter leader Jiang Baichuan, leading Yan Tuo to investigate undercover, bringing Lü Xian (Zhang Yichi) disguised as a feng shui master.

The museum houses over 7,500 stone-carving artifacts from the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties through to the Republican period, including household objects, agricultural tools, temple steles, and inscriptions, all of which reflect the distinctive features of Zhejiang folk stone carving.

Within the museum grounds, reconstructed traditional courtyard houses are connected by a covered long corridor, creating what museum designers describe as “a garden within the museum, and a museum within the garden” (“馆中有园,园中有馆” guǎn zhōng yǒu yuán, yuán zhōng yǒu guǎn). The museum’s design philosophy aligns with the drama’s mythology: boundaries prove permeable, with rural scenery flowing into refined landscaping, nature into culture, and interior into exterior.

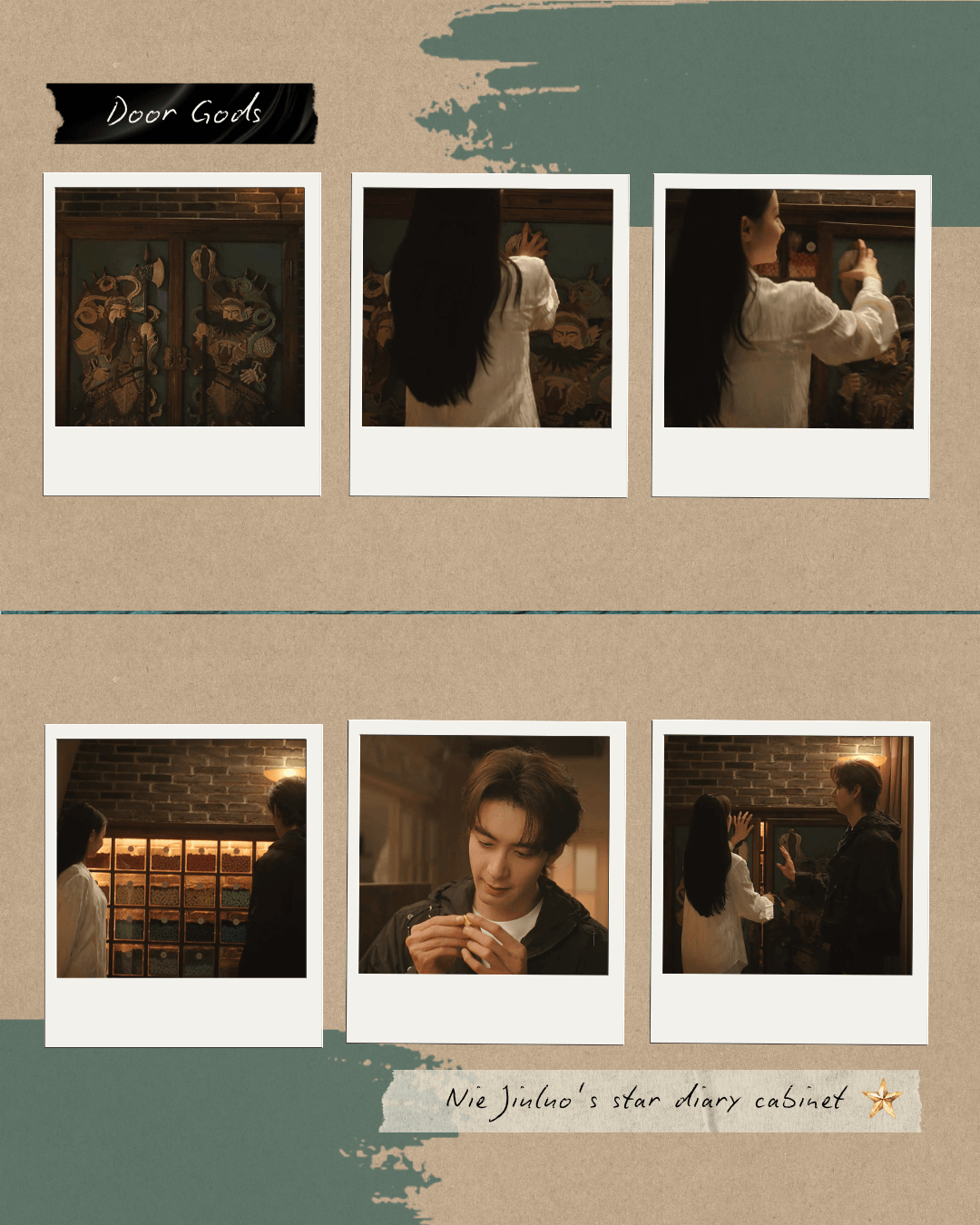

Door Gods

Nie Jiuluo’s cabinet of paper-star diary entries features door gods (门神 ménshén) guarding its front doors. Two armored warriors face inward in a protective stance, gripping weapons. These deities have guarded Chinese entrances for over two millennia, their iconography evolving from ancient spirits into martial generals, civil officials, and blessing-bestowing figures.

The ‘Classic of Mountains and Seas’ mentions Shentu (神荼) and Yulei (郁垒), who are among the earliest named door gods in Chinese tradition. Their names are traditionally pronounced Shēnshū and Yùlǜ according to ancient readings preserved in classical scholarship, though in modern Mandarin the characters read as Shéntú and Yùlěi:

In the Eastern Sea lies Mount Dushuo. Upon it grows a great peach tree, its branches coiling for three thousand li. To the northeast, on its lowest bough, is the Ghost Gate, through which myriad ghosts pass in and out. There are two deities: one named Shentu (Shenshu), the other Yulei (Yulü). They are charged with inspecting and overseeing those ghosts that harm humans.

东海度朔山有大桃树,蟠屈三千里,其卑枝东北曰鬼门,万鬼出入也。有二神,一曰神荼,一曰郁垒,主阅领众鬼之害人者。

dōnghǎi dùshuò shān yǒu dà táoshù, pánqū sānqiān lǐ, qí bēi zhī dōngběi yuē guǐmén, wàn guǐ chūrù yě. yǒu èr shén, yī yuē Shéntú (Shēnshū), yī yuē Yùlěi (Yùlǜ), zhǔ yuèlǐng zhòng guǐ zhī hài rén zhě.

The door gods on Nie Jiuluo’s cabinet serve as a visual metaphor for the boundaries she protects: the line between her peaceful vocation as a sculptor and her duties as Nanshan Hunter, between the self she presents to the outside world and the secrets and precious memories she guards.

In a drama exploring physical and symbolic boundaries, these door guardians represent the ancient role of protector. The Nanshan Hunters are living versions of these figures, stationed between worlds, their existence devoted to ensuring what dwells below does not breach the surface.

Zhong Kui as Door God

During the Tang dynasty, Zhong Kui took on the mantle of a door god who captures and devours ghosts in Chinese folk culture. People affixed images of Zhong Kui to their doors for the Spring Festival New Year and Dragon Boat Festival to ward off evil and expel malevolent spirits, establishing a tradition of protection that the Nanshan Hunters inherit and embody.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Chinese Door Gods Zhong Kui & Guan Yu Archival Print on Xuan Paper by Leechees (Freya) on Etsy.

Dunhuang Star Chart

As Nie Jiuluo and Yan Tuo descend into their final mission, she points out the Nanshan Hunters’ stone-carved star chart, claiming it is over two thousand years old, predating the oldest known Chinese star chart.

Nie Jiuluo is referring to the Dunhuang Star Chart (《敦煌星图》Dūnhuáng Xīngtú) from the Tang dynasty, widely regarded as one of the earliest surviving star atlases in the world. Sealed within the Dunhuang Mogao Caves’ Library Cave (敦煌莫高窟藏经洞 Dūnhuáng Mògāo Kū Cángjīng Dòng), also known as Cave 17, the chart came to light in 1900. It was later acquired by Aurel Stein in 1907 and taken to Britain, where it remains housed in the British Library today. The chart’s authorship is tentatively linked to the Tang dynasty astronomer Li Chunfeng, who is believed to have presented it to Emperor Taizong, though the evidence remains inconclusive. Rather than being a purely impressionistic sketch, the chart depicts the sky through systematic observation and clear map projection techniques. Modern analysis suggests positional accuracy within a few degrees, reflecting generations of careful sky observation.

The Nanshan Hunters’ claim to an ancient star chart positions them as keepers of knowledge predating recorded history, linking their struggle to humanity’s age-old conflict with the natural world. Their role is inscribed in the heavens, suggesting that the battle between human and fiend is as old as the stars.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Dunhuang Star Map Restored Art Print (Lunar Month 8) by ScienceArtPrints (Steven) on Etsy.

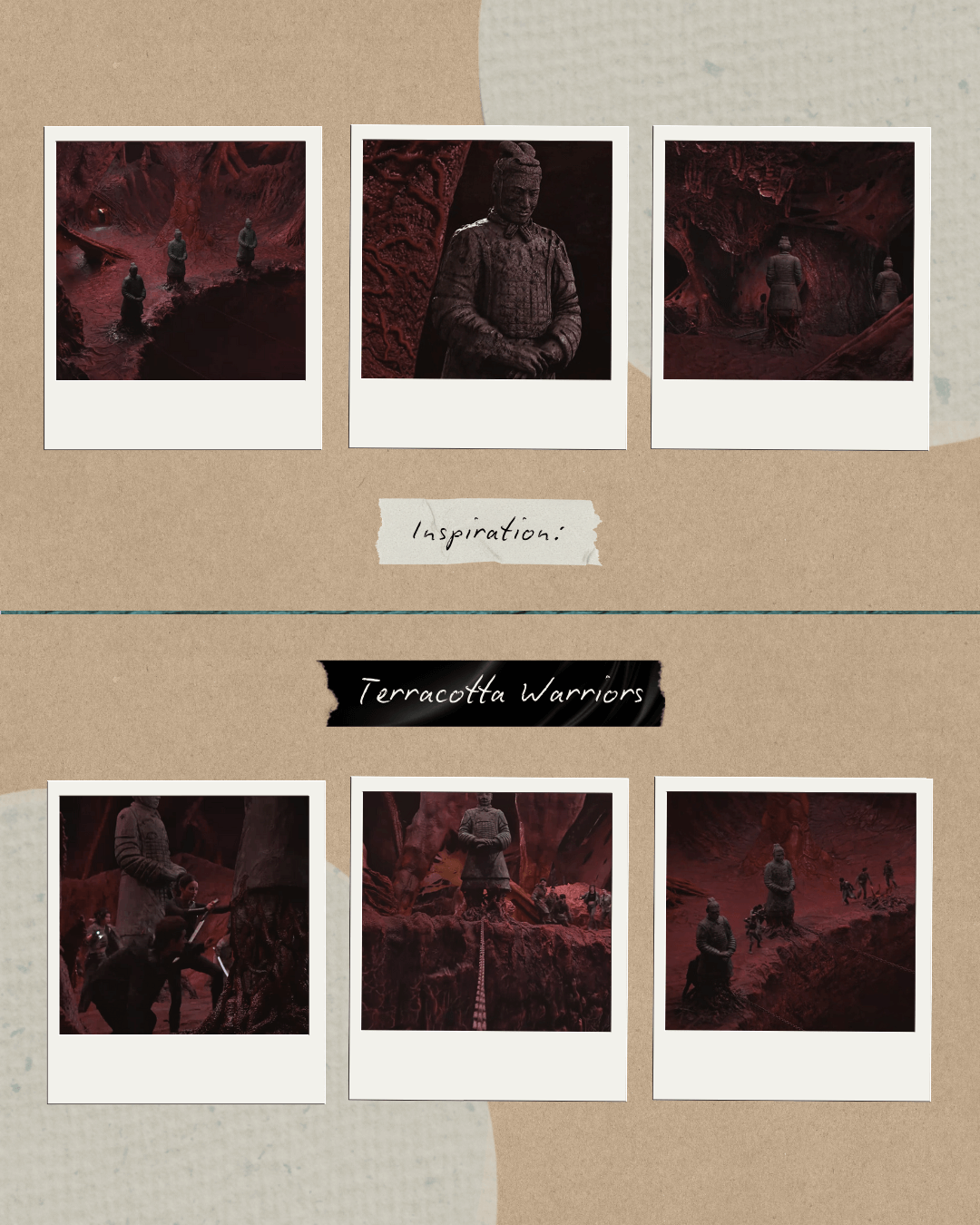

Terracotta Warriors

Emperor Qin Shi Huang, founder of the Qin dynasty, is infamously associated with the quest for immortality. Historical records describe him dispatching envoys to search for the fabled Penglai Islands in pursuit of life-extending elixirs and patronizing alchemists whose experiments involved cinnabar, the mercury sulfide ore used to make such elixirs. His imperial tours are often understood, at least in part, as being driven by this search, as he sought out masters of magic and alchemy believed to possess secrets of longevity. Qin Shi Huang died in 210 BCE during one of these journeys, and a persistent modern hypothesis holds that his death may have been caused by prolonged consumption of mercury-based elixirs. His mausoleum near Xi’an, guarded by a vast terracotta army, stands as an unprecedented projection of imperial power beyond death.

In the ‘Love on the Turquoise Land’ novel, Qin soldiers searching for the elixir unearth Earth Fiends, while the drama presents sculptures in the Twilight Chasm modeled after the Terracotta Warriors (兵马俑 bīngmǎ yǒng). These figures represent a significant shift in Chinese burial customs. During earlier dynasties, human sacrifice accompanied elite burials. The gradual social changes of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods brought reform, leading to the practice of tomb figurine burial (俑葬 yǒngzàng), in which clay or wooden figurines were used to replace living sacrifices. The Terracotta Warriors represent this tradition’s most ambitious expression: an entire army of warriors and horses rendered in clay.

The Nanshan Hunters represent an inversion of figurine burial. Where the Terracotta Warriors replaced human sacrifice with clay figures, the Hunters sacrifice their actual bodies to guard the boundary between worlds. Unlike clay figures standing sentinel over a dead emperor, the Nanshan Hunters guard the living, and they can be broken, infected, and transformed into monsters.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Terracotta Warriors Xi’an Travel Poster Art Print designed by TheOttieCo on Etsy.

Teal Color Terracotta Warrior Glazed Clay Figurines from SendingItVintage on Etsy.

Terracotta Warriors Hand-Painted Earrings by FestyDesigns on Etsy.

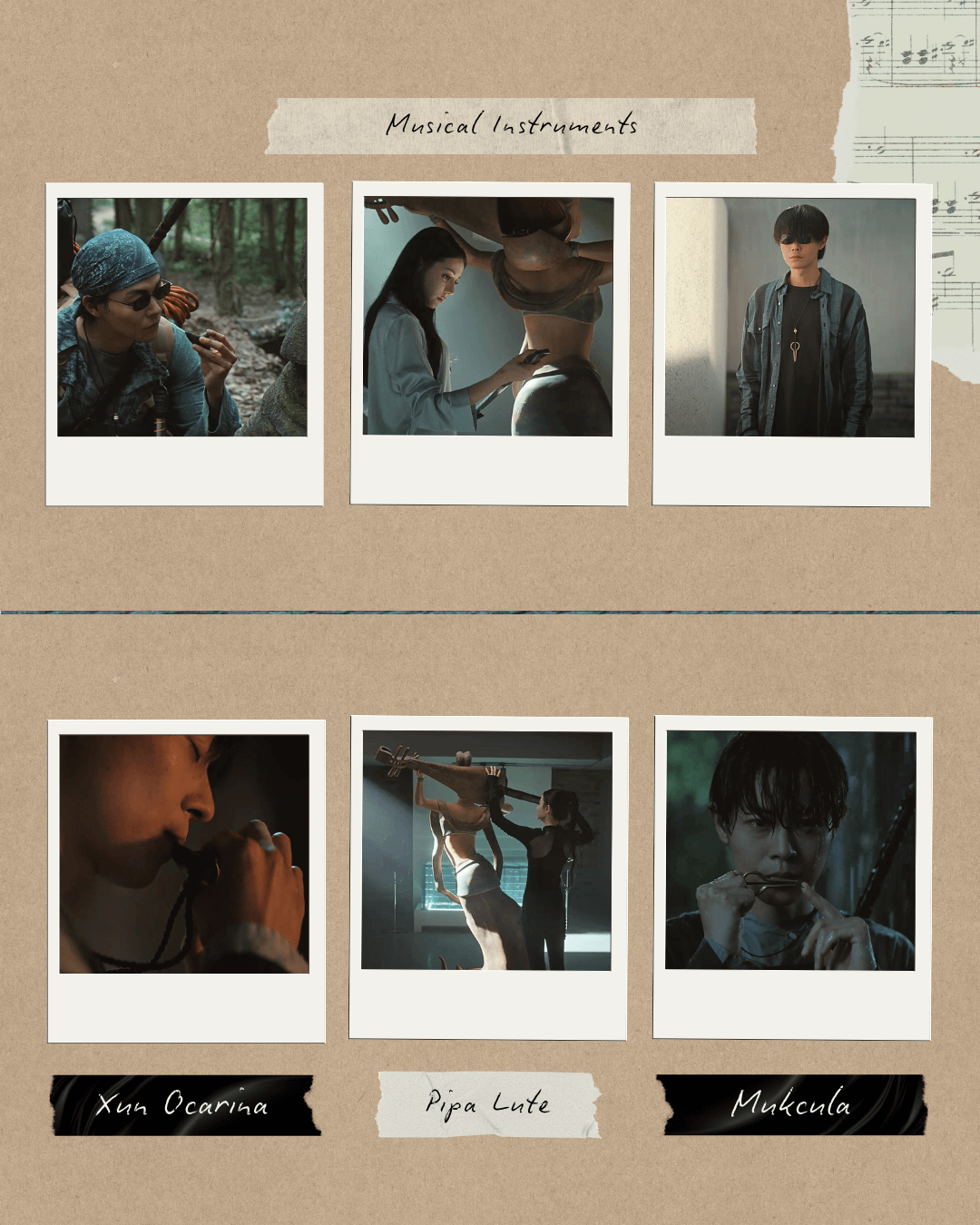

Traditional Musical Instruments

Musical instruments in ‘Love on the Turquoise Land’ summon, control, and communicate across the boundary between human and fiend, yet they are also vehicles for ritual and meaning-making. Through music, the drama suggests that humans demonstrate the presence of beauty and tradition even amid conflict.

Xun: The Ocarina

In mythology, Nüwa is credited with creating the xun (埙 xūn), a globular wind instrument. Its mellow, mournful tone has long accompanied funerary and sacred rituals honoring the dead. The xun is one of China’s oldest musical instruments, with origins stretching back to the Stone Age. Early hunters used a rope-tethered stone or clay ball for striking prey. When thrown, these balls made sounds, and over time, they evolved from hunting tools into musical instruments. These balls are sometimes called ‘stone meteor’ (石流星 shí liúxīng), a term that links them to the drama’s mythological origin story of a meteor striking the land in the Southern Mountains.

The earliest xun were simple vessel flutes with a single blowing hole. Versions with finger holes gradually emerged, enabling players to produce different pitches. By the Shang dynasty, craftsmen standardized designs, often with around five holes, making controlled melodic performance more practical. From the Zhou dynasty onward, the xun became closely associated with court and ritual music, a tradition that continued through later dynasties. Modern craftsmen have developed versions with nine or more holes, expanding the instrument’s range while preserving its distinctive ancient sound.

In the drama, Ma Hanzi (Zheng Hao) reads about the ‘Xun of Nanshan’ (南山之埙 Nánshān zhī Xūn), also translated as the ‘Nanshan Ocarina,’ from the ‘Miscellaneous Records of the Nanshan Hunters’ (《南山猎人杂记》Nánshān Lièrén Zájì):

Bricks of Nanshan (‘Southern Mountain’) are formed from the soil of the Turquoise Land, tempered with natural fire. When gathered and shaped, they become an instrument... It resounds near and far, able to penetrate the netherworld. In that underworld dwell the Ba, crouching beneath the Turquoise Land, answering the call of the bricks.

Xing Shen uses the ‘Xun of Nanshan’ to summon Ba to aid in battle against Earth Fiends, the instrument’s mournful tone calling forth those who dwell below. The shape of his xun resembles the ox-head-shaped xun of the Ningxia Hui people.

Pipa: The Lute

Nie Jiuluo stores her Mad Blade inside a sculpture of a courtesan holding a pipa (琵琶 pípa). The password is a melody plucked on its strings.

The pipa is a Chinese traditional plucked string instrument, typically with four strings, a pear-shaped body, and a fretted fingerboard. It emerged from early lute instruments, including round-bodied, straight-necked forms in the Qin and Han dynasties and pear-shaped types that arrived via Central Asian routes during and after the Han dynasty. An Eastern Han text, the Shiming (《释名》Shìmíng), explains that the name pipa derives from two opposing playing techniques: a forward stroke (pi) and a backward stroke (pa). In earlier periods, the name was written with various characters before the standard written form settled as 琵琶.

The instrument flourished during the Tang dynasty's banquet music (燕乐 yànyuè) era, marking its first golden age and becoming central to both imperial court ensembles and folk performances.

The pipa is the most commonly depicted instrument in Dunhuang murals, appearing in hundreds of painted scenes. Early depictions commonly show it held horizontally, and the famous ‘reverse posture’ (反弹琵琶 fǎntán pípa) — a performer playing the pipa held behind her back — appears in Middle Tang-period murals. This is exactly how Nie Jiuluo’s sculpture holds the instrument, connecting her to a tradition of cultural refinement even as she wields a blade in battle. This pipa sculpture symbolizes Jiuluo’s public image as a cultured sculptor while concealing her identity as a Nanshan Hunter, intertwining art and weapon.

Mukcula: The Daur People’s Instrument

Xing Shen wears a mukcula (木库莲 mùkùlián) around his neck, which he uses to communicate with a captive Earth Fiend. This traditional instrument of the Daur ethnic group, an indigenous people predominantly located in Northeast China, consists of a pincer-shaped steel frame with a thin steel tongue. Its origins are rooted in a folk legend that tells of women imitating the sound of the wind through grass to express their yearning for their deceased husbands. For over a thousand years, it has existed as a living expression of northern shamanic culture.

In the drama, Xing Shen uses the instrument to summon an Earth Fiend he has tamed as a companion, reinforcing the drama’s message that connection persists even between supposed enemies.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Ceramic Ocarina Chinese Flute Instrument made by AuraTunes (Maya) on Etsy.

Hand-Carved Bronze Pipa Pendant made by OldWorldBrass (Jasper) on Etsy.

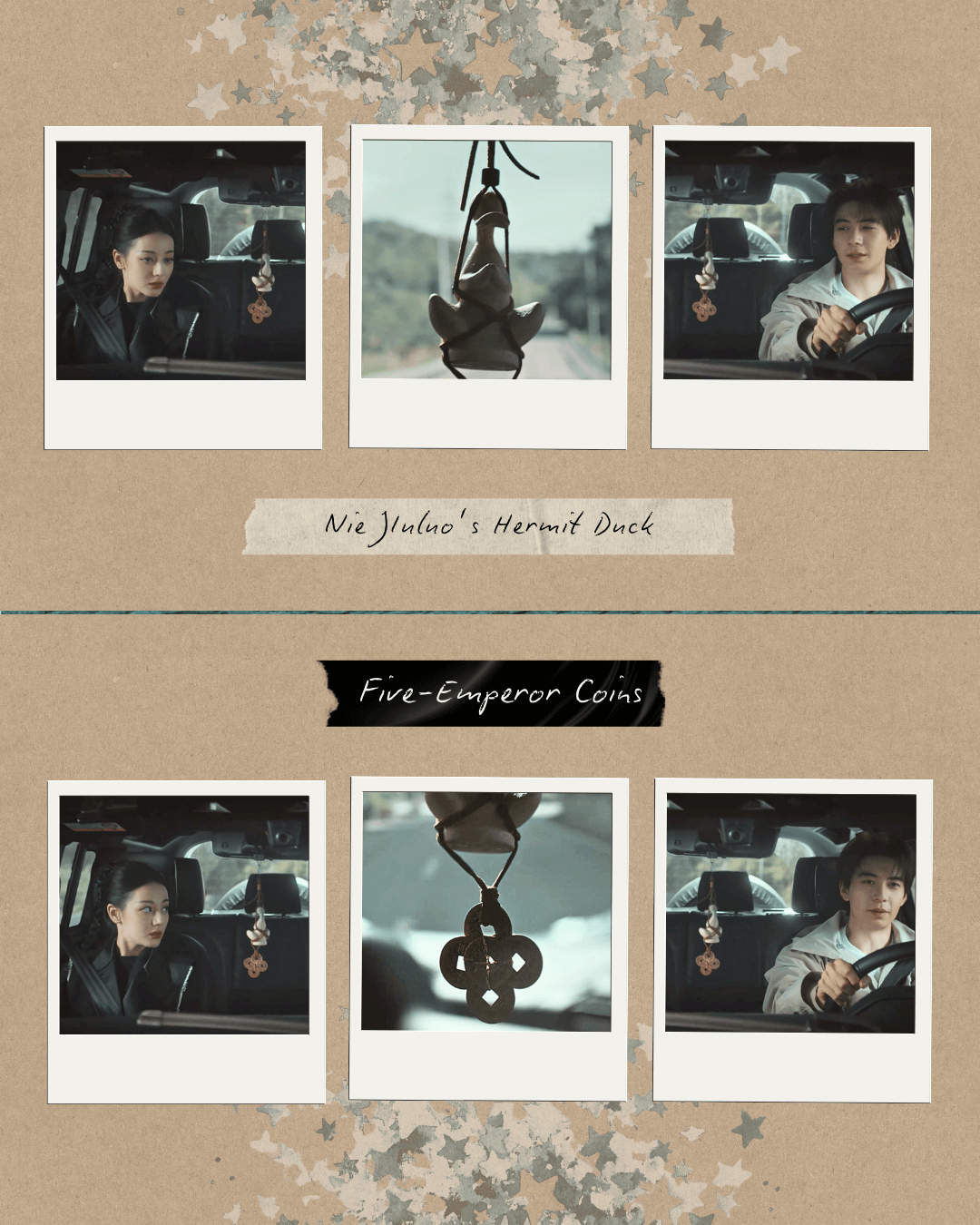

Five-Emperor Coins

Yan Tuo hangs Five-Emperor Coins (五帝钱 wǔdì qián) around Nie Jiuluo’s trademark Hermit Duck design (隐者鸭 Yǐnzhě Yā), using it as a car charm. His quirky DIY accessory reflects a common practice of hanging coin charms in vehicles to attract blessings and ensure peace and safety.

Ancient Chinese copper coins carry cultural significance beyond their monetary value. Their round outer edge and square center embody the cosmological principle of ‘round heaven and square earth’ (天圆地方 tiānyuán dìfāng), symbolizing cosmic order and reflecting the ideal of ‘the oneness of heaven and humanity’ (天人合一 tiānrén héyī).

In folk and feng shui practice, strings of five copper coins are associated with the five directions and Five Phases (五行 wǔxíng): wood, fire, earth, metal, and water, which describe cyclical patterns of transformation in the natural world. Within this framework, the coins are traditionally treated as auspicious charms that gather protection and draw in blessings.

Originally, ‘Five Emperors’ referred to celestial rulers linked to the Five Phases in early ritual cosmology. Over time, the phrase came to be associated with historical emperors in folk culture.

Today, Five-Emperor Coins most commonly refer to five Qing dynasty emperors and the coins minted during their reigns: Shunzhi, Kangxi, Yongzheng, Qianlong, and Jiaqing, whose eras are often remembered for strength and stability. Another interpretation honors five notable emperors across different dynasties whose reigns each produced representative coins: Qin Shi Huang, Emperor Wu of Han, Emperor Taizong of Tang, Emperor Taizu of Song, and the Yongle Emperor of Ming. In this light, the coins can be read as emblems of auspicious rule and cultivated virtue.

Yan Tuo’s car charm signals his alignment with cosmic order and human tradition. The coins anchor him to a worldview that values balance and harmony, reflecting his choice to invoke order when chaos threatens, and to maintain ritual, calling upon blessings.

Tiffilosophy Picks:

Carved Five-Emperor Coins Pendant for car, phone, bag from YINYUTING on Etsy.

Five-Emperor Coin Ornament made by Luminapearl (Yanyan) on Etsy.

Lucky Cat Feng Shui Five Emperors Coin Keychain Charm designed by AffinyGifts (Omer) on Etsy.

Five-Emperor and Bamboo Design Silver-Plated Adjustable Bracelet designed by MOONLITCREATIONS77 on Etsy.

Five-Emperor Coins of five Qing emperors: Shunzhi, Kangxi, Yongzheng, Qianlong, and Jiaqing.

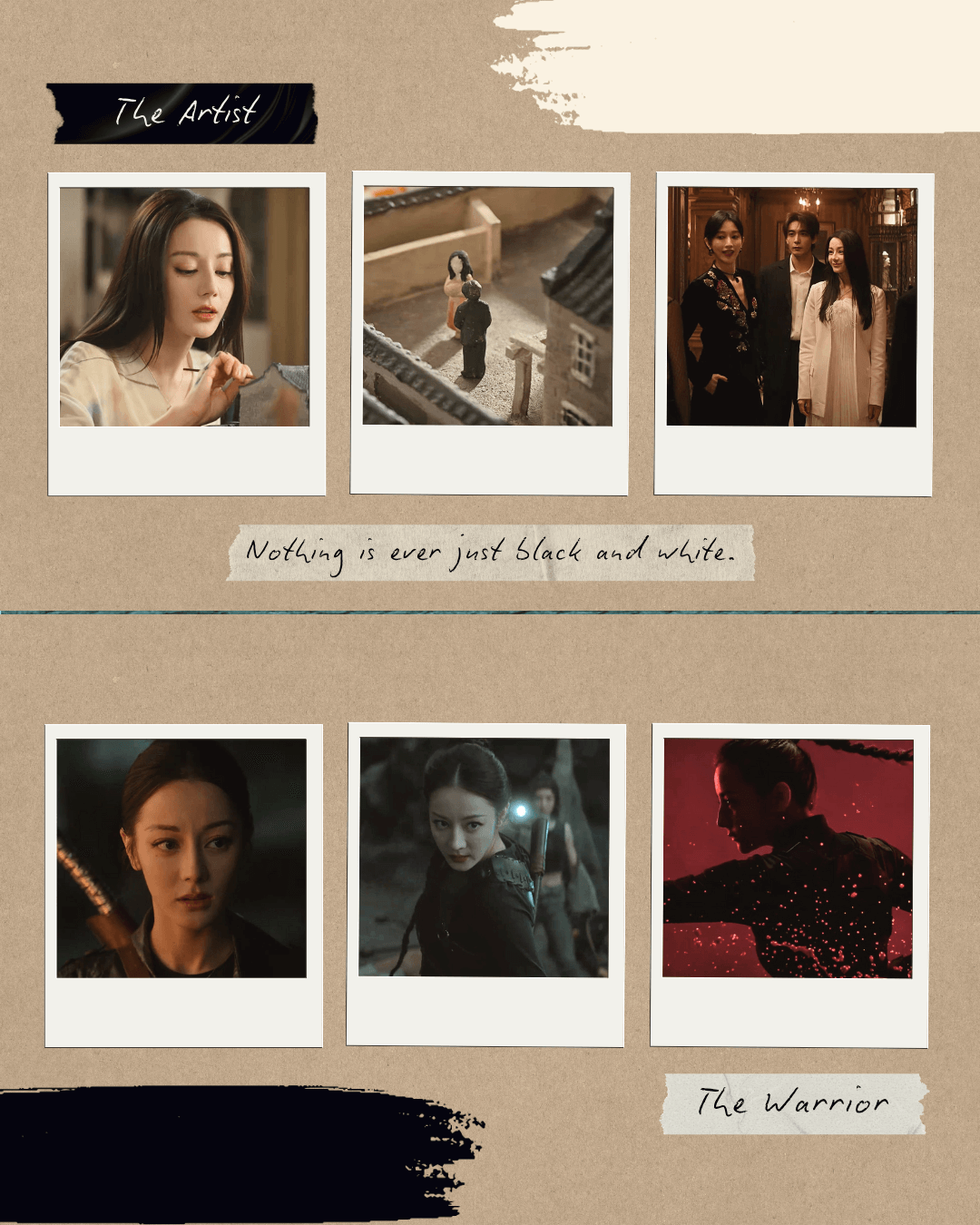

The Artist and the Warrior

Perhaps what ‘Love on the Turquoise Land’ illuminates is the reality that gave rise to ancient myths: the often brutal struggle for survival that ultimately forged civilization. The ‘Classic of Mountains and Seas’ can be understood as a survival manual of sorts, cataloguing creatures, resources, and threats. It is a record born of conflict and written out of necessity. Yet embedded within that primal struggle is a desire for harmony and unity with natural forces, both beautiful and destructive.

Nüwa and Fuxi, with their intertwined serpent tails, depict these complementary forces. Humans and fiends are two branches of the same cosmic serpent, formed from the same divine clay. What ultimately distinguishes humanity is not inherent moral superiority, but the capacity for conscious choice — fighting not merely for survival, but to preserve the fragile equilibrium that allows coexistence in a world where “good” and “evil” often depend on which side of the boundary we stand.

Humanity also means acknowledging our flaws and contradictions, our capacity for both beauty and violence, compassion and cruelty, sacrifice and selfishness. In this vein, Nie Jiuluo can be seen as both a warrior and an artist, choosing to fight for what she believes in, yet returning to sculpture when the battle ends. The beauty of a peaceful, creative life is what she fights to protect, and her conscious way of being human in the world.

Dilraba Dilmurat reflects on Nie Jiuluo’s journey in a Weibo post:

The duty on your shoulders is no longer a crushing shackle. It’s become the confidence that holds you up and carries you forward. Through choice after difficult choice, you’ve grown ever more steady and decisive. This version of you — so lively, so resilient — is genuinely incredible!!! … Through this journey, you also helped me understand something: real freedom is never about running away. It’s about, after all you’ve seen and survived, still being able to protect the purity in your heart — and having the courage to choose the life you truly want.

Co-star Chen Xingxu writes about Yan Tuo in his own post at the conclusion of the drama’s broadcast:

If A-Luo was the beam of light in your fate that pierced the dark, then Uncle Changxi (Lin Peng), Lin Ling (Liang Songqing), and Lü Xian became the courage that let you keep moving toward that light … Strength was never about putting your sharpness on display. It’s about seeing the world’s cruelty clearly, and still choosing to hold fast to your original intentions.

To be human is to hold the tension between warrior and artist, to fight when necessary but not let fighting define us, and to choose, consciously, again and again, to protect and create beauty in this world.