Starring Meng Ziyi and Li Yunrui in breakout roles, Blossom brings to life a fictional world inspired by the Ming dynasty, anchoring imaginative storytelling in historical detail to create a drama that feels both sweeping and grounded in realism.

“One of the defining features of ‘Blossom’ is that it is deeply rooted in a Ming dynasty setting,” screenwriter Jia Binbin explains at the drama’s panel event for RedNote.

“Our priority was to ensure that the story feels realistic. Then, on top of this realistic foundation, we wanted to explore whether the characters can break free from predetermined constraints of fate.”

This Ming dynasty backdrop, with its emphasis on Confucian values and, as Jia Binbin puts it, “deeply embedded patriarchal and military power structures,” perfectly complements the story’s themes.

To prepare for their roles, the cast underwent an intensive 15-day training workshop on Ming dynasty rituals, customs, etiquette, and expression. They learned everything, from how to sit, stand, hold objects, eat, and drink, to how to practice cha hua (插花 chā huā), the traditional art of flower arranging, and cha dao (茶道 chá dào), the Chinese tea ceremony.

Here are some of the most fascinating historical details embedded in the drama’s world.

For a more detailed exploration of Ming dynasty clothing, see Best Ming Dynasty Style Moments in ‘Blossom.’

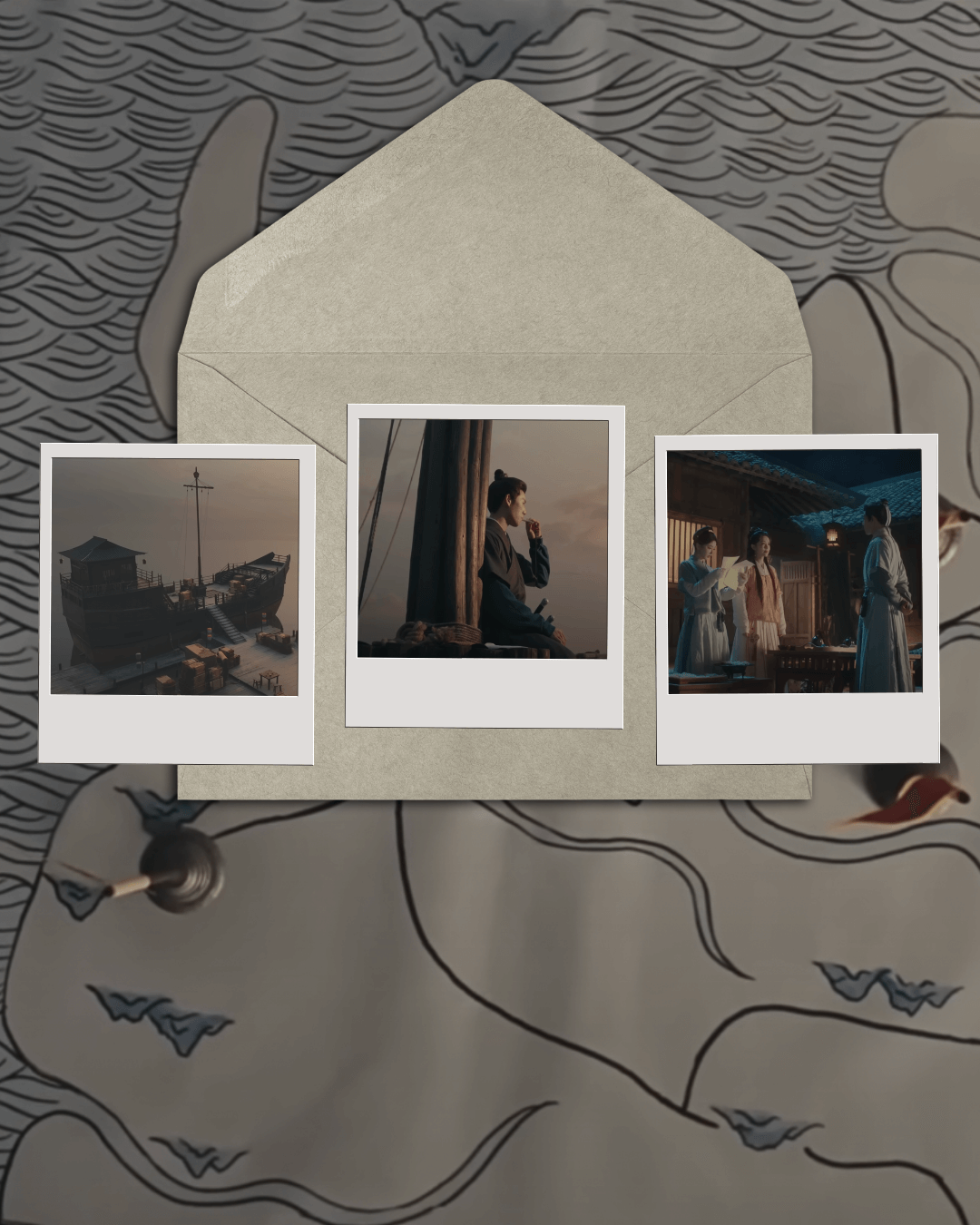

Maritime Trade

Historical Events and Figures

In ‘Blossom,’ Dou Zhao (Meng Ziyi) and Miao Ansu (Kong Xue’er) navigate the turbulent waters of maritime trade, with some help from Ji Yong (Xia Zhiguang), as they face strict regulations and the seizure of their merchant ships. Meanwhile, Song Mo (Li Yunrui) and the Ding army battle pirates on the seas.

Their storylines reflect real historical events and developments during the Ming dynasty, from imperial maritime bans and anti-piracy crackdowns to shifting diplomatic strategies and the gradual loosening of trade restrictions, all while private commerce continued to be regulated.

As the founding emperor of the Ming dynasty, the Hongwu Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang issued the first sea ban (海禁 hǎijìn) in 1371, mandating that all foreign trade be conducted exclusively through official tribute missions. This decree aimed to curb pirate raids and consolidate imperial control over maritime activity.

By the mid-Ming period, restrictions began to ease in an effort to revive trade networks. In 1567, at the end of the Jiajing emperor’s reign and with the ascension of the Longqing emperor, the sea ban was officially lifted. Piracy had been curbed by this time, and maritime trade flourished once again, though crackdowns and turbulence persisted into the Qing dynasty.

Military Strategies

Mandarin Duck Formation

Screenwriter Jia Binbin shared that the unjustly embattled Duke of Ding (Zhang Chenghe), Song Mo’s uncle, was inspired by two Ming dynasty military figures: Hu Zongxian and Qi Jiguang.

Hu Zongxian, a general and politician of the Ming dynasty, led efforts against pirate raids during the reign of the Jiajing emperor, capturing the infamous pirate lord Wang Zhi in 1557. Despite his contributions, his reputation was later tarnished, only to be rehabilitated decades after his death.

Qi Jiguang, one of the most renowned generals of his time, played a pivotal role in developing military strategies to combat piracy in the 16th century. Among them was the iconic mandarin duck formation (鴛鴦陣 yuānyāng zhèn), which is reenacted in the drama’s climactic battle scene.

Qi Jiguang eventually fell out of favor with the Wanli emperor and was dismissed from office, returning home in disgrace to spend his final years in poverty. Like Hu Zongxian, his reputation was restored posthumously, and he came to be celebrated as one of China’s great military heroes.

The drama’s directors, Zeng Qingjie and Guo Feng, together with their production team, conducted extensive research and drew on historical records and documentaries to reconstruct the mandarin duck formation for the climactic battle scene, in which Song Mo and the Ding army face off against Prince Qing (Dong Zifan) and Song Han (Yan An).

While variations existed, the formation was primarily structured as a symmetrical squad with a front-to-back configuration consisting of a squad leader, two saber-and-shield bearers, two soldiers wielding spiked spears, four long-spear bearers, two polearm soldiers, and logistical personnel.

The formation could be split into smaller units, such as the ‘second power formation’ or the ‘third power formation,’ making it highly adaptable to shifting battlefield conditions.

A distinctive weapon used in the mandarin duck formation is the xian (筅 xiǎn), a multi-tipped spear, also known as the langxian (狼筅 lángxiǎn) or ‘wolf brush.’ Its angled tip and branching spikes created a bristling silhouette. Qi Jiguang referenced the langxian in his seminal manual ‘New Treatise on Military Efficiency’ (《紀效新書》jìxiào xīnshū) and is believed to have developed it specifically for combat in the Southern terrain of Zhejiang and Fujian.

Later, Qi Jiguang integrated musket teams into the Ming army, a development that is also referenced in the drama.

In the drama’s final battle, soldiers behind Song Mo can be seen carrying xian, cleverly camouflaged with foliage. At a crucial moment, Dou Zhao delivers the final blow with a hand cannon, showcasing the admirable teamwork and coordination of our leading couple.

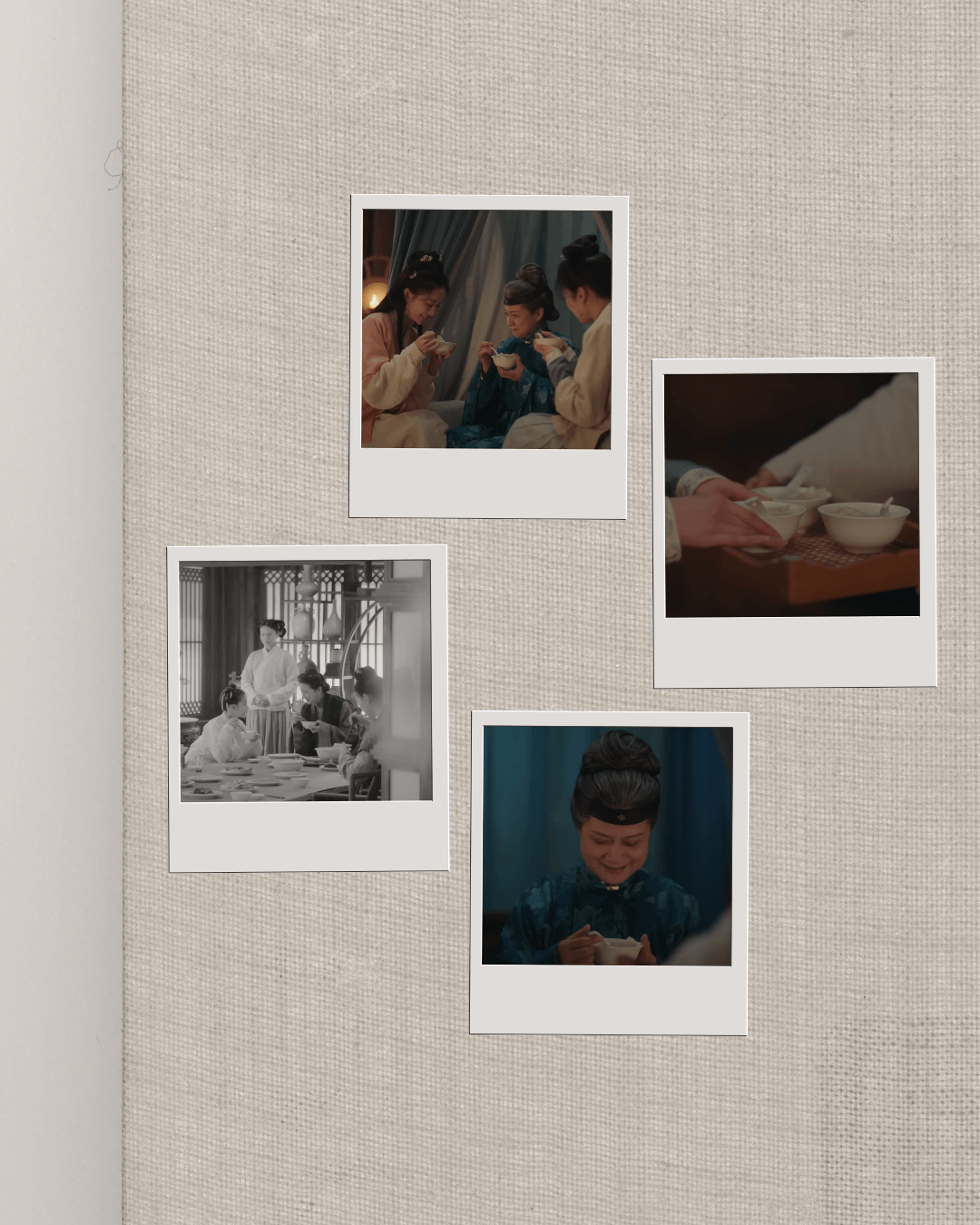

Regional Cuisine

Ji’an Cuisine and Historical Details

Granny Cui (Mu Liyan), Dou Zhao grandmother, is a native of Ji’an, a region renowned for producing the highest number of top scholars (状元 zhuàngyuán) in the imperial examinations during the Ming dynasty. This detail supports the family’s scholarly roots and highlights their remarkable literary talent, which extends to the women of the household.

The drama also infuses regional culinary traditions to enhance its historical authenticity. In a heartwarming scene, Dou Zhao and Zhao Zhangru (Liu Meitong) prepare lotus root dumplings (藕饺 ǒu jiāo) for Granny Cui and reminisce about making the dish clumsily in their childhood.

Lotus root dumplings are a beloved delicacy from Ji’an, which is known for incorporating lotus into its cuisine. These thoughtful touches not only enrich the cultural realism of the drama but also add warmth to the familial bond between the characters.

Science and Technology

Rain Gauge

‘Blossom’ integrates Ming dynasty technological advancements into its narrative, crafting an enchanting world filled with curiosities and surprises while remaining grounded in historical reality.

At the Dou residence, Dou Zhao overhears a group of young men gossiping about which of her friends are deemed fit (or not) for marriage. Determined to get back at them for their crude remarks, she triggers a tipping mechanism on a nearby rain gauge (量雨器 liáng yǔ qì), drenching them with water.

“What on earth is that?! It stinks!” the boys cry.

“This is a rain gauge from the Ministry of Works, used by various provinces to measure rainfall and prevent disasters. It must not be tampered with,” the gentlemanly Wu Shan (Quan Yilun) remarks, stepping in to side with Dou Zhao as the boys scramble to get rid of the contraption. justice served.

Co-director Guo Feng, who researched the rain gauge for the drama, elaborates enthusiastically during a Q&A session:

That was a rain gauge specifically used in the Ming dynasty to measure seasonal rainfall variations.

During the reign of the Yongle emperor, local governors were required to use standardized rain gauges to record precipitation levels and report them to the court. This enabled more accurate forecasting of agricultural yields across different regions.

Arts, Entertainment, and Design

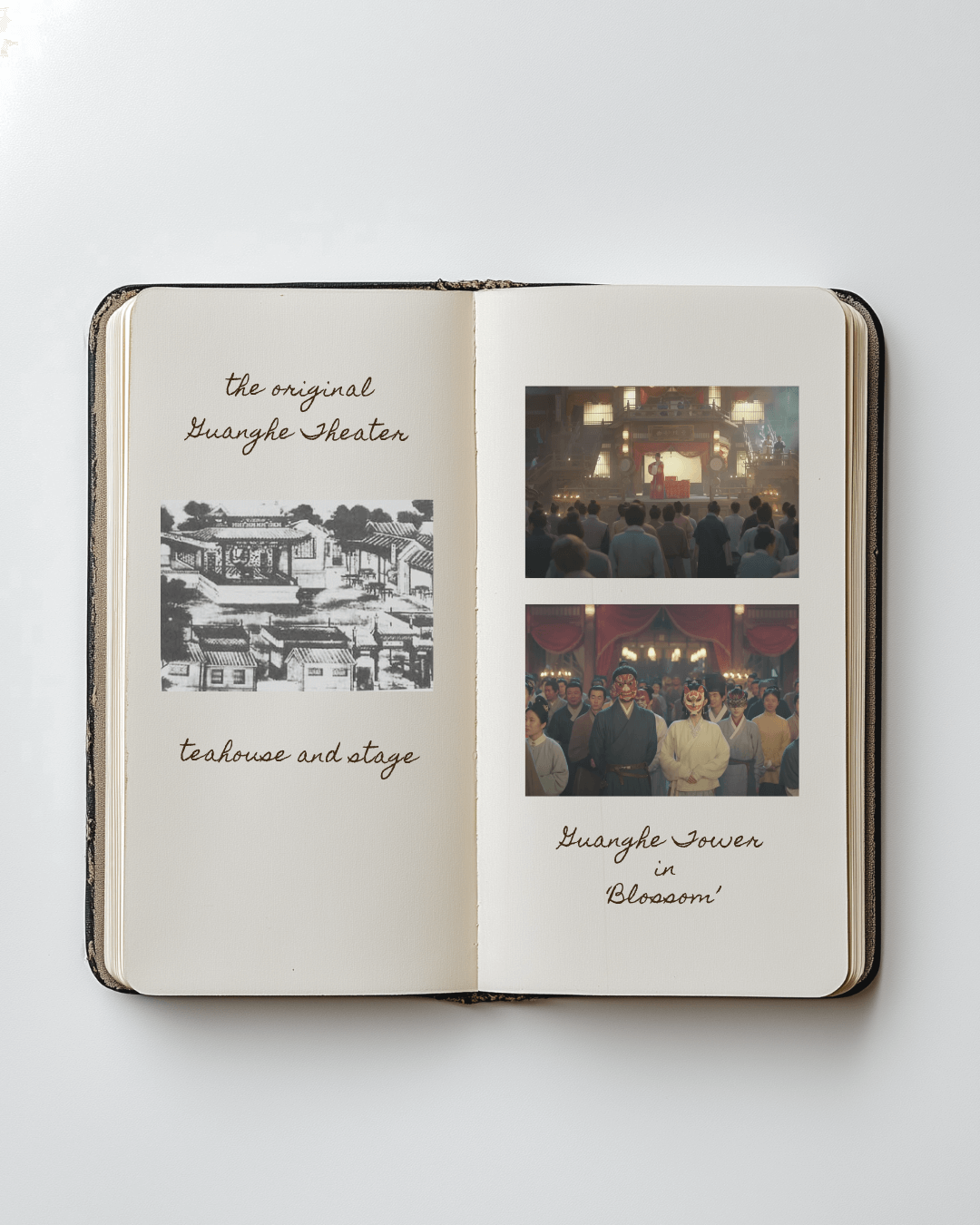

Guanghe Tower

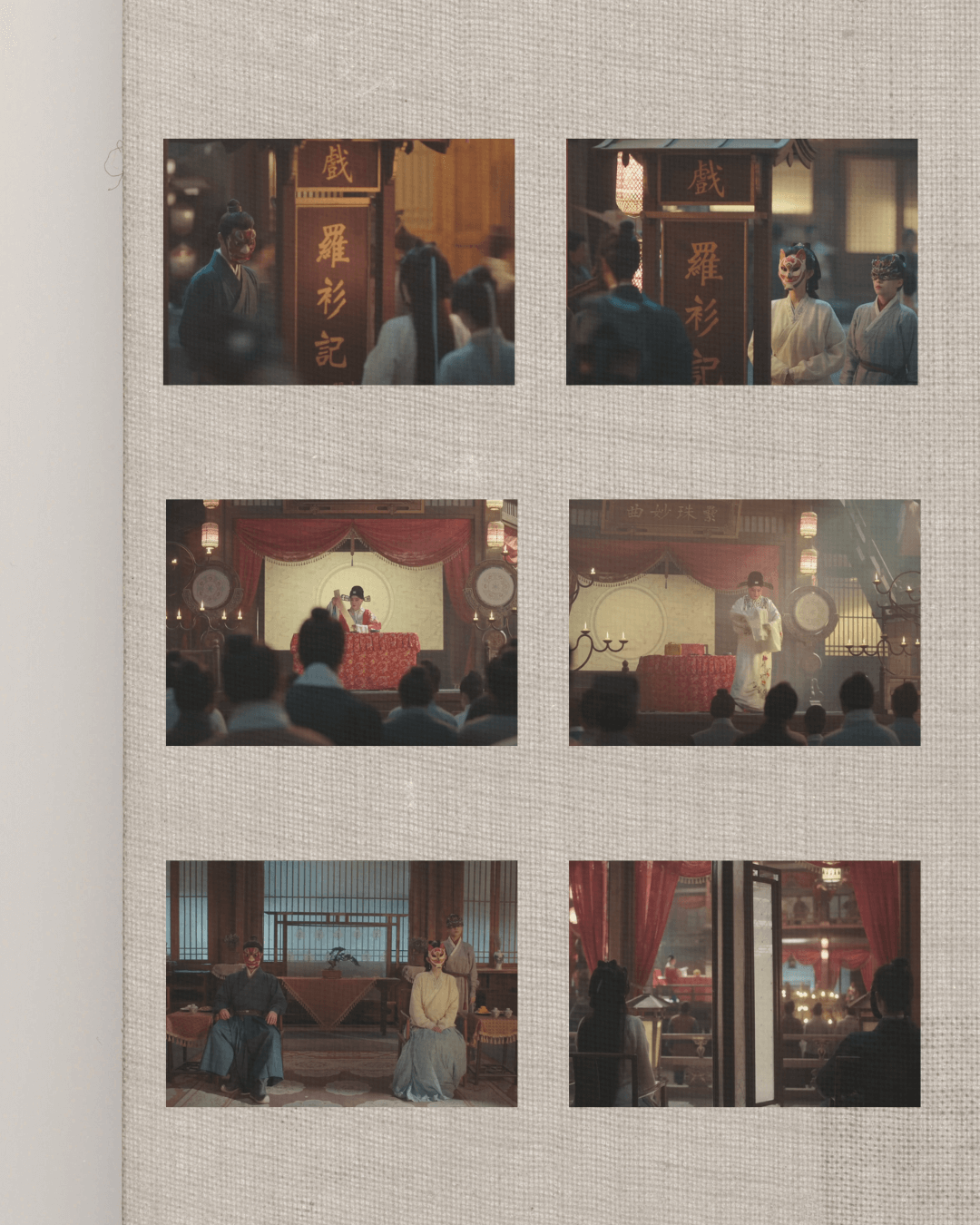

One of the key locations in the drama is Guanghe Tower (广和楼 guǎnghé lóu), a theater that Song Mo acquires and uses as an undercover operations base for the Ding Army.

This setting is modeled after a real historical site that once stood in Beijing’s Qianmen District. Built in the late Ming dynasty, Guanghe Tower, also known as Guanghe Theater, was originally a tea house with a theater pavilion situated within the private gardens of the Zha family. Over time, it evolved into one of Beijing’s most renowned opera houses, ranking among the four great theaters of the capital during its heyday in the Qing dynasty.

All the plays performed at Guanghe Tower in the drama reflect core Confucian values in Ming society, including the Three Fundamental Bonds and the Five Constant Virtues (三纲五常 sāngāng wǔcháng).

‘Tale of the Gauze Robe’

‘Tale of the Gauze Robe’ (《罗衫记》 luó shān jì) is the play that Dou Zhao and Song Mo watch when they first meet again in the next life. Right away, Dou Zhao recognizes how the story mirrors Song Mo’s internal struggle between filial piety and his moral conscience under the shadow of a tyrannical father.

Set during the Yongle era of the Ming dynasty, ‘Tale of the Gauze Robe’ follows an official named Xu Jizu as he investigates local cases. One day, he encounters a Daoist nun named Zheng Yuesu, who accuses his father, Xu Neng, of murder. As Xu Jizu delves deeper into the case, he uncovers the shocking truth: the Daoist nun is his biological mother, and the man who raised him killed his real father.

Torn between personal loyalty and a duty to uphold justice, Xu Jizu ultimately chooses to sentence Xu Neng and reunite with his mother.

‘Tale of the Gauze Robe’ was originally a Ming dynasty novel by an anonymous author, later adapted into the Kunqu opera, ‘White Gauze Robe’ (《白罗衫》 bái luó shān).

By employing the literary device of a play within a play, staged against the backdrop of Ming dynasty architecture, entertainment, and leisure activities, ‘Blossom’ creates an authentic cultural atmosphere while offering insight into the trials and tribulations our protagonists face through the performances they watch.