The Double, a heroine-driven revenge drama starring Wu Jinyan and Wang Xingyue, is staged in a fictional dynasty that draws from historical paintings, sculptures, costume traditions, and classical texts, reimagining these sources with a modern sensibility to craft a visually striking world.

The drama’s styling director Song Xiaotao explains in a behind-the-scenes production special:

Because the drama is set in a fictionalized dynasty, there was a lot of room to experiment with the overall styling. We didn’t strictly adhere to the aesthetics of ancient periods, and also integrated many aspects of modern taste.

In shaping both its narrative and visual world to resonate with modern tastes, ‘The Double’ aligns itself with a trending Chinese genre known as shuang ju (爽剧 shuǎng jù), best translated as ‘cathartic dramas.’ This genre emerged from web novels as shuang wen (爽文 shuǎng wén), or ‘cathartic literature’, before gaining momentum in visual media with the boom of micro short dramas.

Shuang ju centers on revenge, the reversal of fortune, and the pursuit of justice. Their appeal lies more in emotional payoff than in logical plot development — the immediate rush of release and satisfaction that comes from watching villains punished, underdogs prevail, and justice served as if we ourselves had lived through the ordeal and triumphed.

It is by leaning into shuang ju sensibilities that ‘The Double’ makes its mark, both commercially and artistically. Through its polished costumes, makeup, props, and set design, the drama builds a world that is at once dark and opulent, moody yet rich in period detail, and heightened with dramatic embellishments that amplify the intensity and cathartic release at the heart of the genre.

The production takes inspiration from depictions of daily life in the Sui and Tang dynasties and the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, while grounding the drama’s styling in the refined elegance of Song dynasty aesthetics.

Here are some of the standout features of hair styling, costume, makeup, props, and accessories that link ‘The Double’ to historical art and culture across the ages.

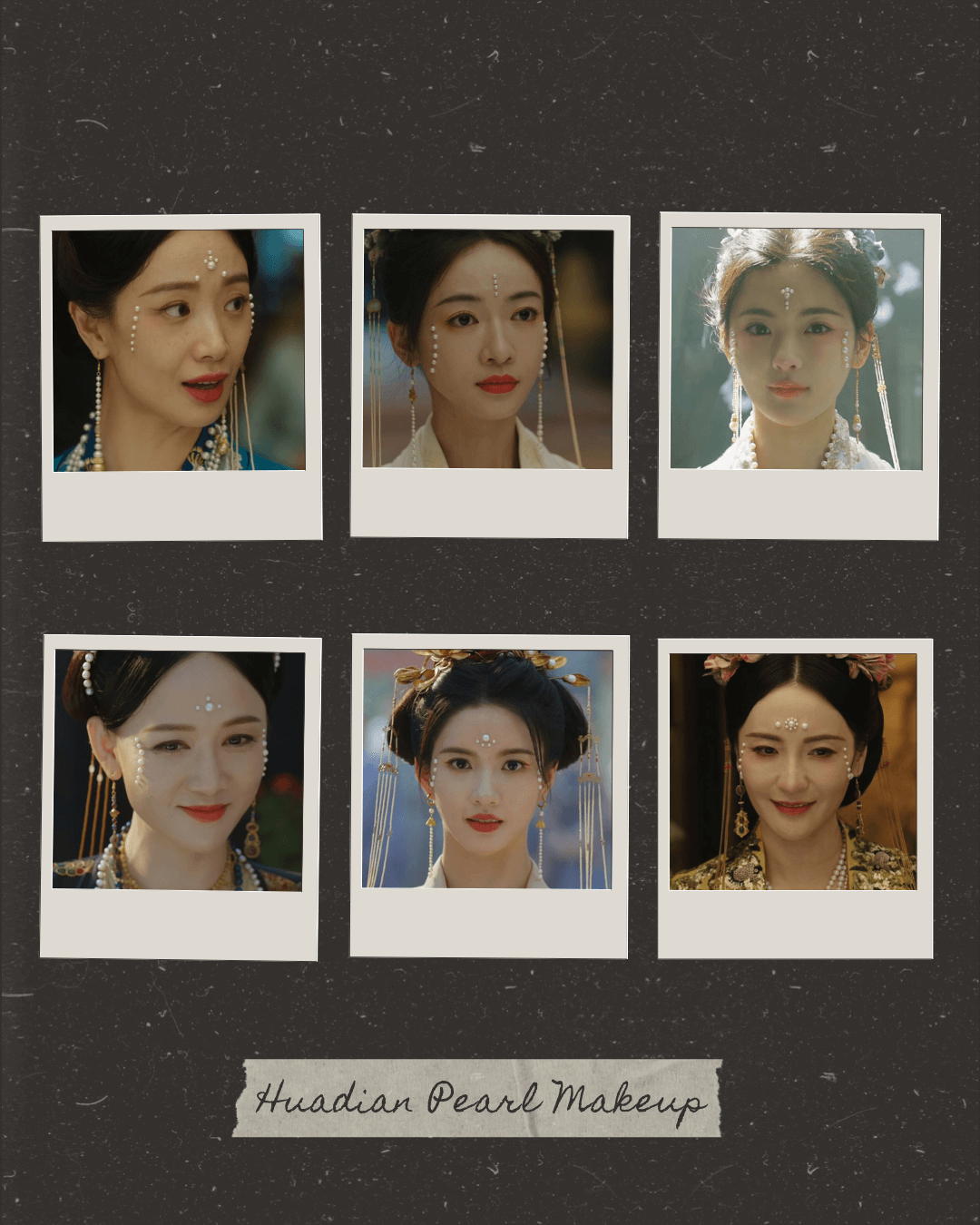

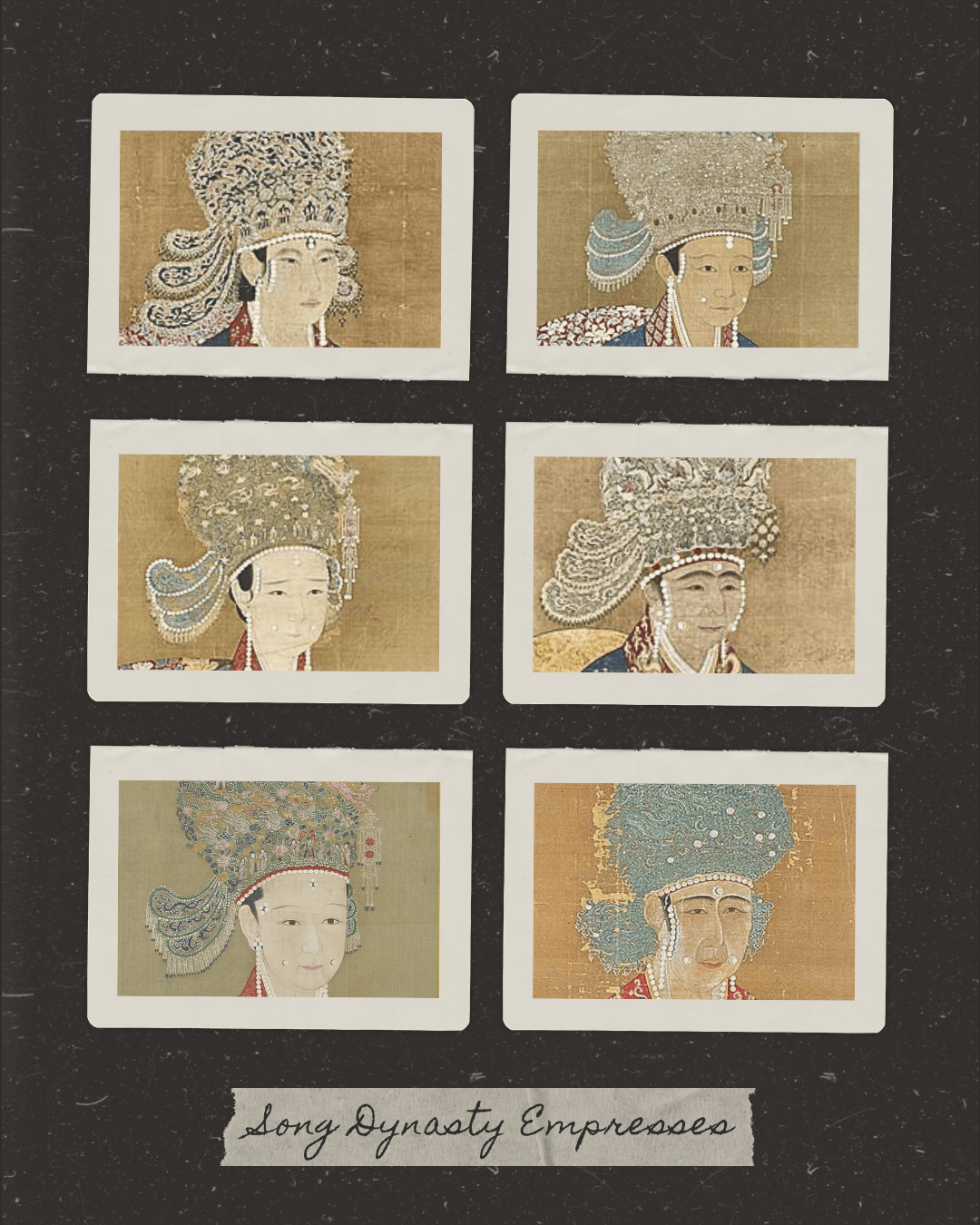

Pearl Makeup

The pearl-embellished makeup look in ‘The Double’ is inspired by the styles worn by empresses and noblewomen of the Song dynasty, where ornaments adorned the face as markers of beauty and status symbols. In the world of this drama, the more pearls a lady wears on her face, the higher her social standing.

“In the Song dynasty, pearls were the most luxurious form of ornamentation. In ‘The Double,’ every pearl applied to the face is a real pearl,” said makeup director Lin Xiaoli.

These pearls form one type of decorative accent within the broader category of huadian ornamental makeup (花钿妆 huādiàn zhuāng). Huadian consists of ornaments crafted from gold, kingfisher feathers, pearls, or other precious materials, affixed to the forehead and other key areas of the face in floral, animal, and geometric designs.

Song dynasty court portraits depict empresses with pearls affixed to their foreheads, brows, temples, cheeks, and dimples in teardrop, gourd, blossom, and diamond-shaped patterns. These were often mounted on blue-jeweled bases to complement deep blue ceremonial robes and blue-green fengguan ‘phoenix crowns’. Genuine pearls are fixed to the skin using a robust adhesive made from fish bladder.

The drama’s styling borrows directly from this tradition, incorporating Northern Song designs with elongated strip patterns and star-like dots across the face. The drama’s broadcast set this pearl makeup look trending on social media, with beauty bloggers recreating and reinterpreting the styles most memorably worn by Xue Fangfei (Wu Jinyan), Ji Shuran (Joe Chen), Jiang Ruoyao (Liu Xiening), Jiang Li (Yang Chaoyue), Princess Wanning (Li Meng), and Consort Li (Sun Jingjing).

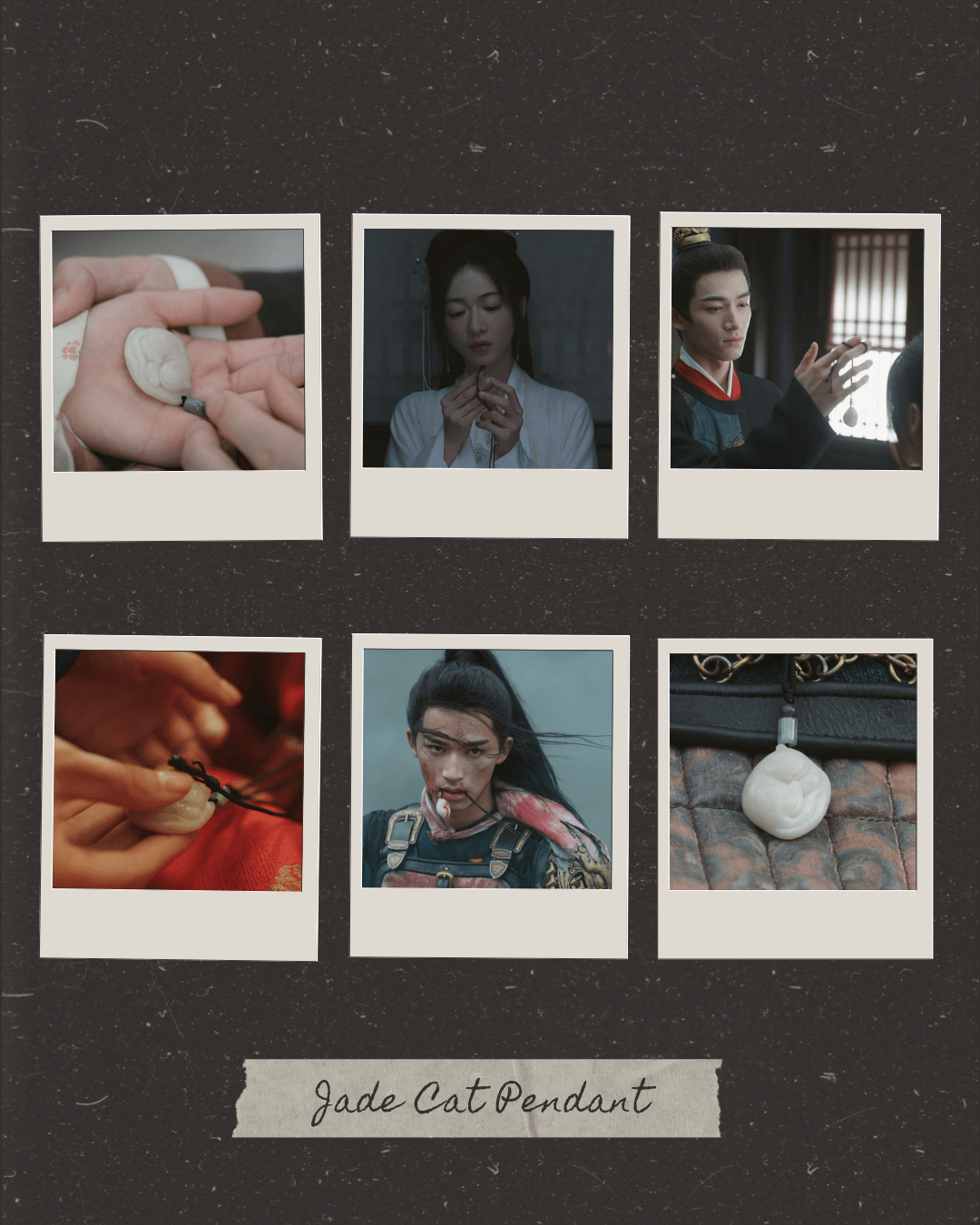

Jade Cat Pendant

One of the most iconic images from the drama shows Xiao Heng (Wang Xingyue) in battle, biting onto a white jade cat pendant belonging to Xue Fangfei (Wu Jinyan), whom he affectionately calls xiao limao (小狸猫 xiǎo límāo), meaning ’little leopard cat,’ or A-li for short.

Jade represents human virtues in traditional Chinese culture. As a Confucian saying in the ‘Book of Rites’ (《礼记》Lǐjì) goes, “a gentleman never parts with his jade without reason” (君子无故,玉不去身 jūnzǐ wú gù, yù bù qù shēn.) Jade pendants were worn on the body as constant reminders of one's virtues. In the drama, Xiao Heng keeps A-li's pendant close to him as a token of love, respect, and their shared quest for justice.

In Chinese folklore, a stray cat entering the house is considered a sign of good luck, with sayings such as ‘cats bring five blessings’ (猫有五福 māo yǒu wǔ fú) and ‘cats enter blessed places’ (猫入福地 māo rù fú dì) have been passed down through generations. According to folk belief, when a cat enters the home, it heralds the arrival of fortune and prosperity.

Jade carvings of cats embody these folk beliefs and classical traditions, symbolizing good fortune for their owners. Xue Fangfei treasures her jade pendant, a gift from her father, who hoped it would bless her with health, protection, and a peaceful life.

The cat-shaped pendant comes to represent Xue Fangfei herself — her resilience, her ability to survive in harsh environments, and the way she, like a stray cat, unexpectedly enters Xiao Heng’s life and captures his heart. Rather than seeing her as a burden or misfortune, as women in the story are so often dismissed and discarded, Xiao Heng cherishes her. She is the one who brings blessings, and he is lucky to have crossed paths with her.

During the Qing dynasty, jade craftsmen carved a variety of white jade cat pendants, reflecting the era’s fondness for feline imagery. Surviving pieces show cats curled into circles, reclining with their paws neatly tucked in, or paired playfully side by side. Some carvings depict a cat chasing mice, while others pair the cat with a butterfly to symbolize longevity.

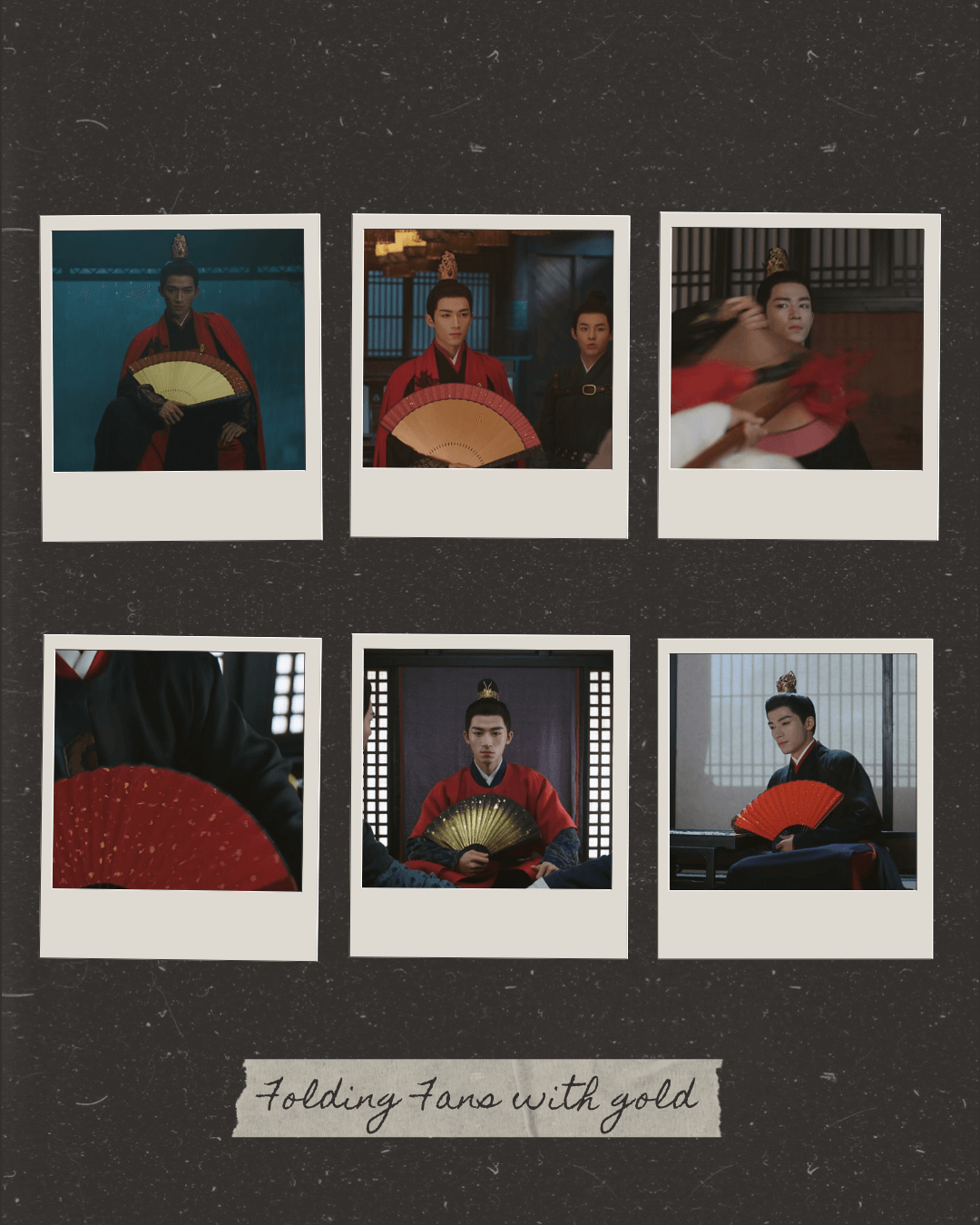

Folding Fans

Xiao Heng, also known as Duke Su, has an impressive collection of fans, with a signature piece being a red folding fan flecked with gold that doubles as a weapon in dazzling fight scenes.

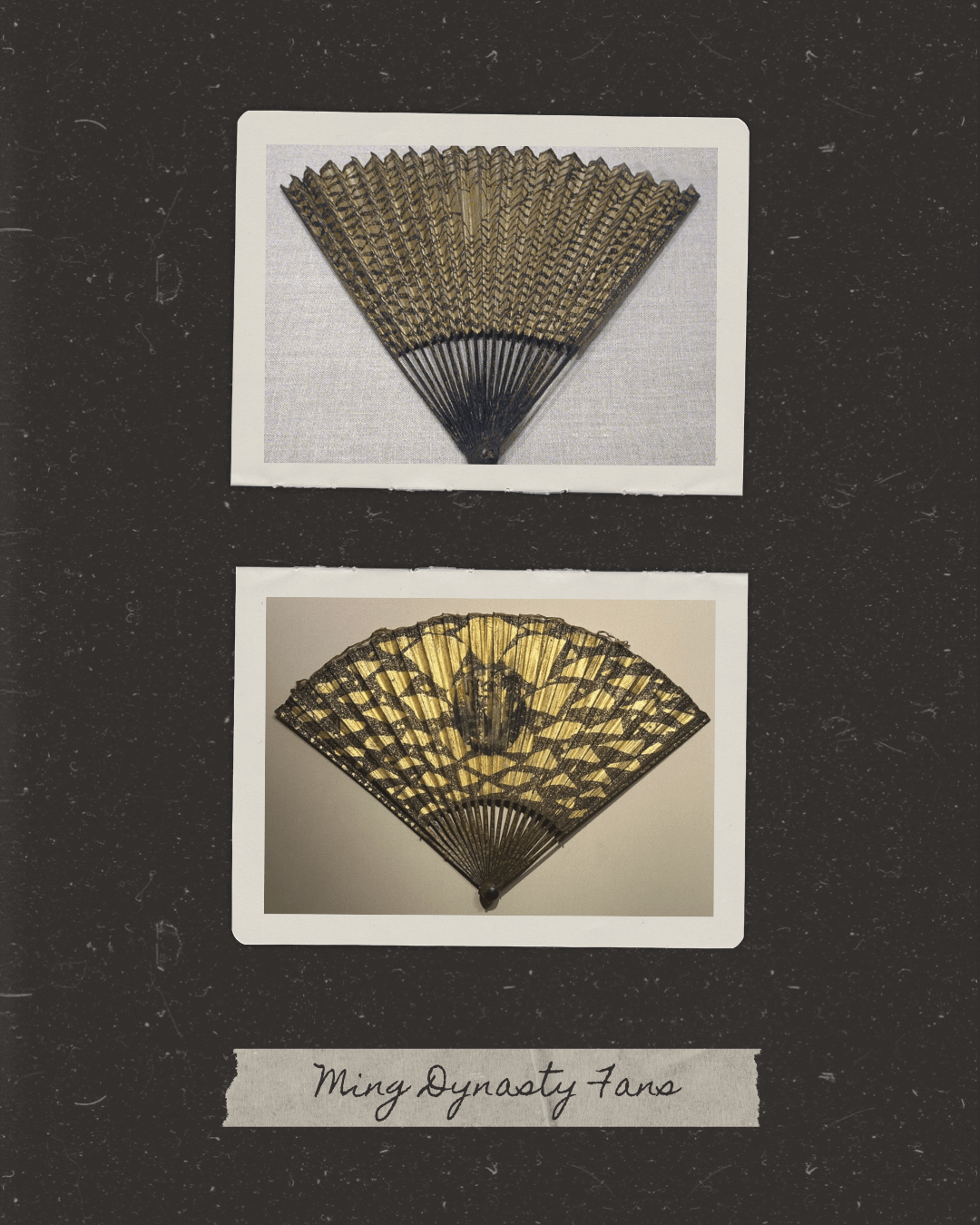

Folding fans like this, made from lacquered bamboo with gold-flecked or gold-painted paper, were crafted in the Ming and Qing dynasties. To achieve these shimmering surfaces, artisans employed a range of decorative techniques working with real gold.

One was sajin (洒金 sǎjīn), literally ‘scattered gold,’ which originated in Tang dynasty papermaking and drew from earlier lacquerware methods. Artisans brushed adhesive onto paper, then sprinkled it with gold leaf or powder before pressing and polishing it.

Another was nijin (泥金 níjīn), or ‘mud gold,’ a technique with origins stretching back to the Neolithic period. Artisans mixed gold flecks with resins or animal glue into a paste, then painted them directly onto a fan’s paper surface.

These techniques, also applied to lacquer and ritual objects, are analogous to Japanese decorative arts such as kirikane (切金 きりかね), introduced through Tang-era Buddhist art, and maki-e (蒔絵 まきえ), a Japanese invention that flourished in the Heian period, which corresponds to China’s Tang, Five Dynasties, and early Song dynasties. Though shaped by trade and cultural exchange, these Chinese and Japanese crafts ultimately developed along distinct paths.

Such fans demanded exceptional skill and costly materials, and by the mid-Ming period, they had become prized at the imperial court as symbols of identity, power, and refinement, far more than as practical tools for keeping cool.

Among scholars, the folding fan served as a canvas for calligraphy, painting, and poetry, often exchanged as gifts of friendship and affection. To hold a fan was to carry learning and taste in the palm of one’s hand.

Within these traditions, Duke Su’s fans take on layered meaning and a striking presence. As he himself declares, his “dignity is beyond doubt,” and his fans fittingly embody his confidence and poise.

Beyond the fantastical world of wuxia and costume dramas, folding fans have also played a significant role in martial arts and dance, including in the fan forms of tai chi or kung fu.

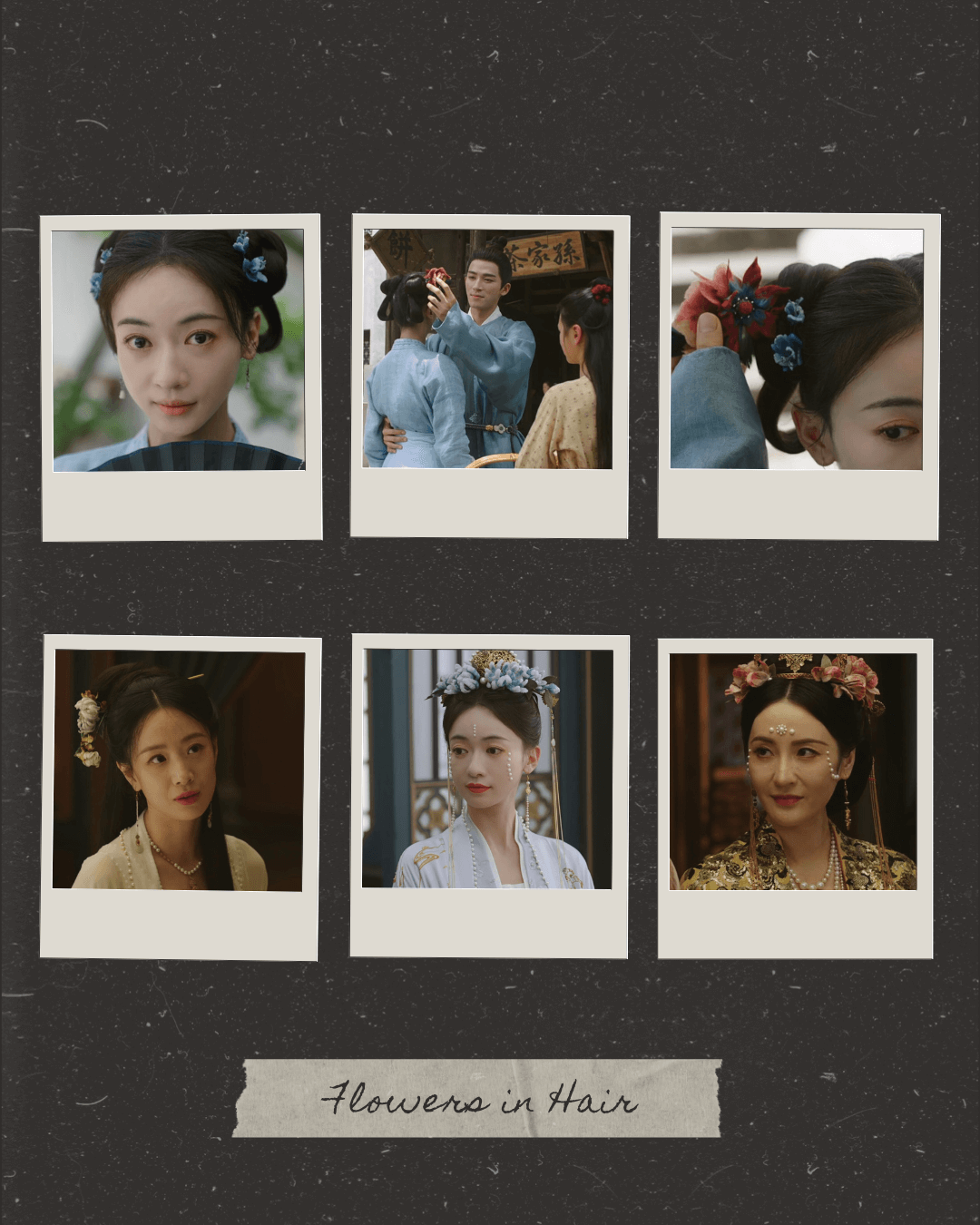

Zanhua: Flower Hairpins

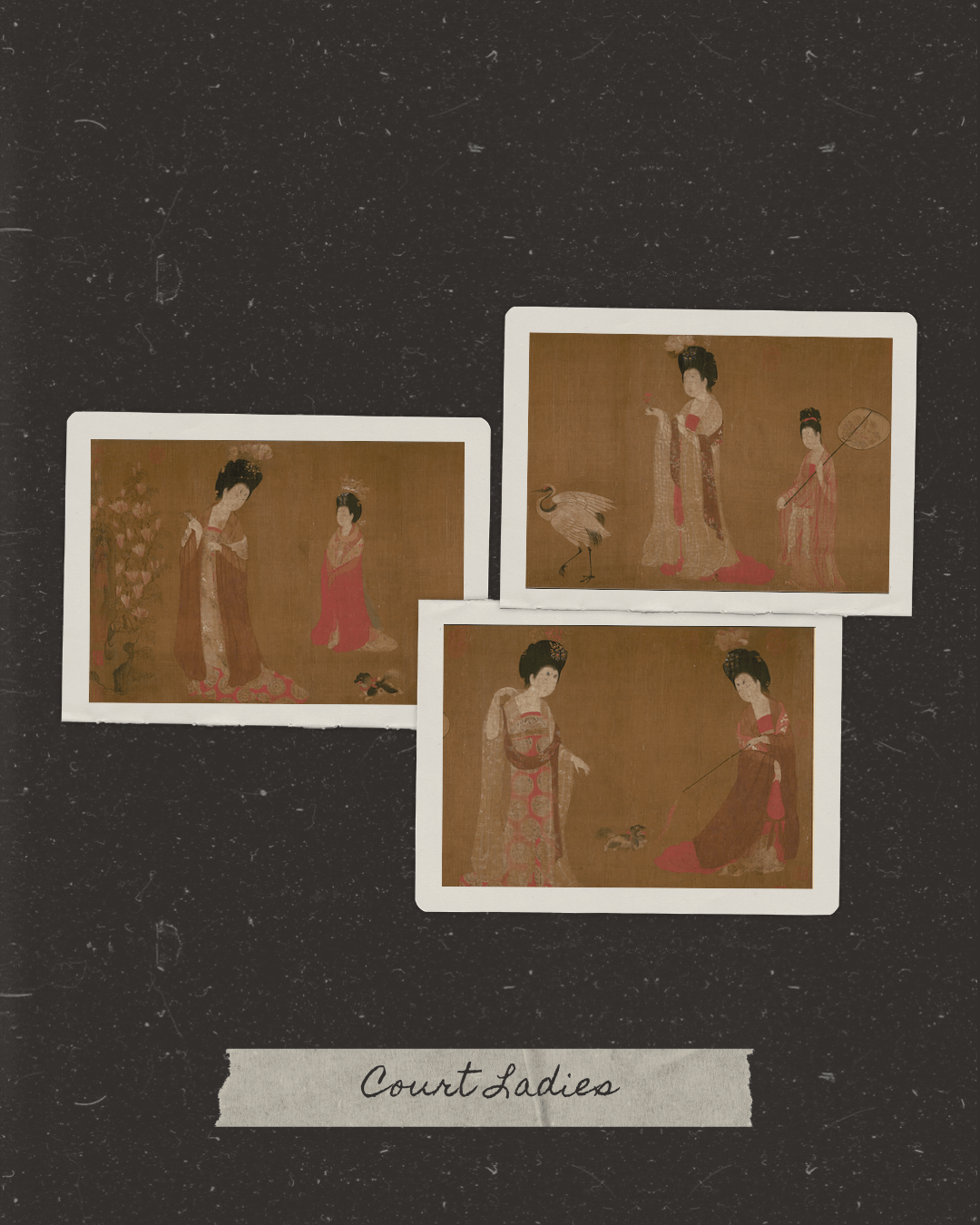

“We looked to portraits of ‘Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers’ as well as the songs and rhapsodies recorded in ‘Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital’ for inspiration,” says hair styling director Lin Anqi.

Specifically, the Tang dynasty palace scroll painting ‘Court Ladies Adorning Their Hair with Flowers’ (《簪花仕女图》 Zānhuā Shìnǚ Tú), attributed to Zhou Fang, inspired the drama’s costume and makeup design team with its depiction of palace women wearing peony, lotus, and hydrangea blossoms atop their high hair buns.

From the Tang through to the Song dynasties, floral ornaments were often worn in hair buns, paired with crowns or headwear, especially during festivals and celebrations.

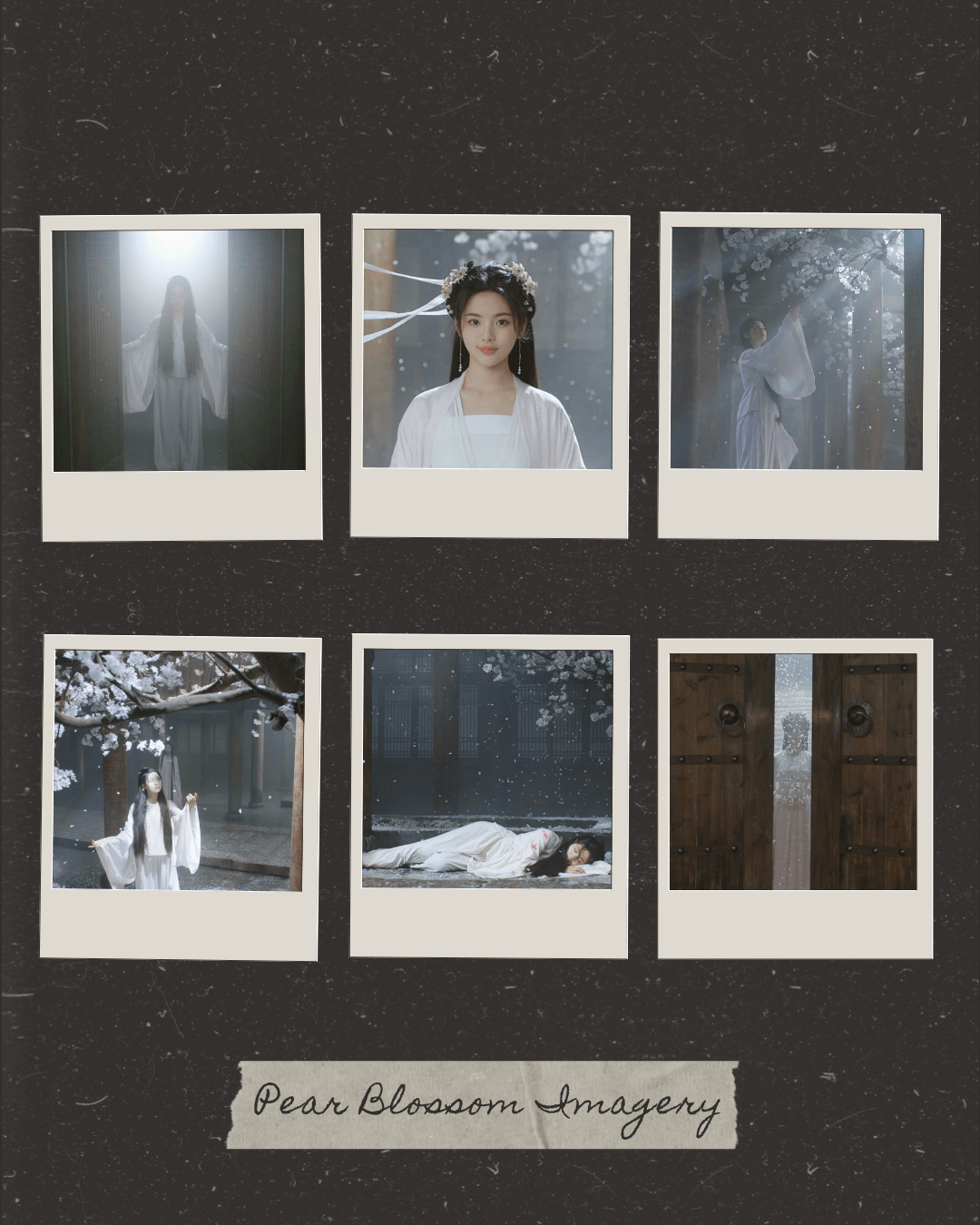

In the drama, Xue Fangfei, disguised as Jiang Li, wears pear blossom hairpins and a gilded flower crown to represent the real Jiang Li (Yang Chaoyue). The li (梨 lí) in Jiang Li means ‘pear.’

In a poignant scene, the dying Jiang Li steps into a courtyard where the pear tree she planted finally flowers, echoing the Tang poem ‘Spring Sorrow’ (《春怨》Chūn Yuàn) by Liu Fangping, which laments the grievances and injustices experienced by women:

In a lonely, empty courtyard as spring draws to a close,

pear blossoms cover the ground, and the doors stay closed.

寂寞空庭春欲晚,

梨花满地不开门。

jìmò kōng tíng chūn yù wǎn,

líhuā mǎn dì bù kāi mén.

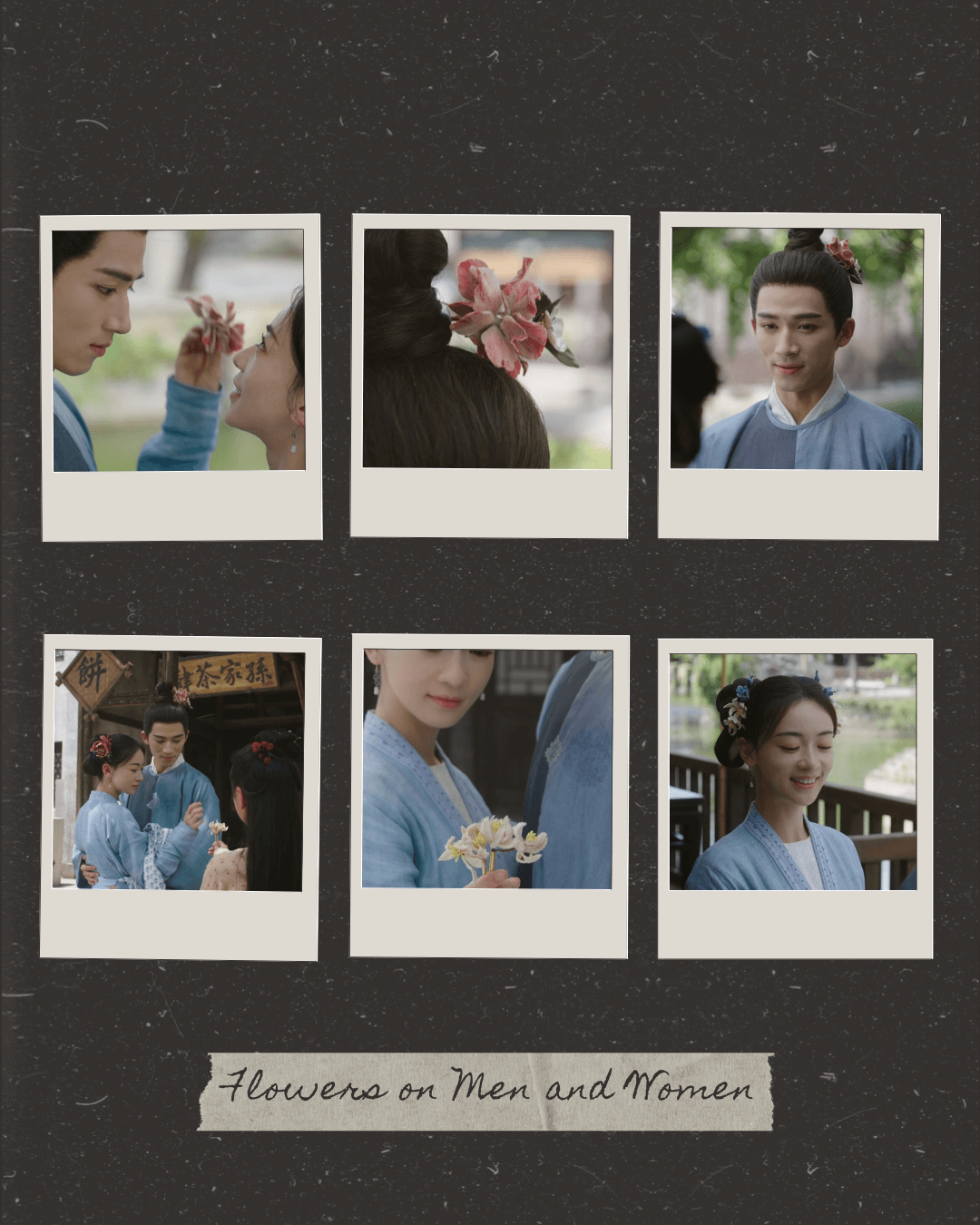

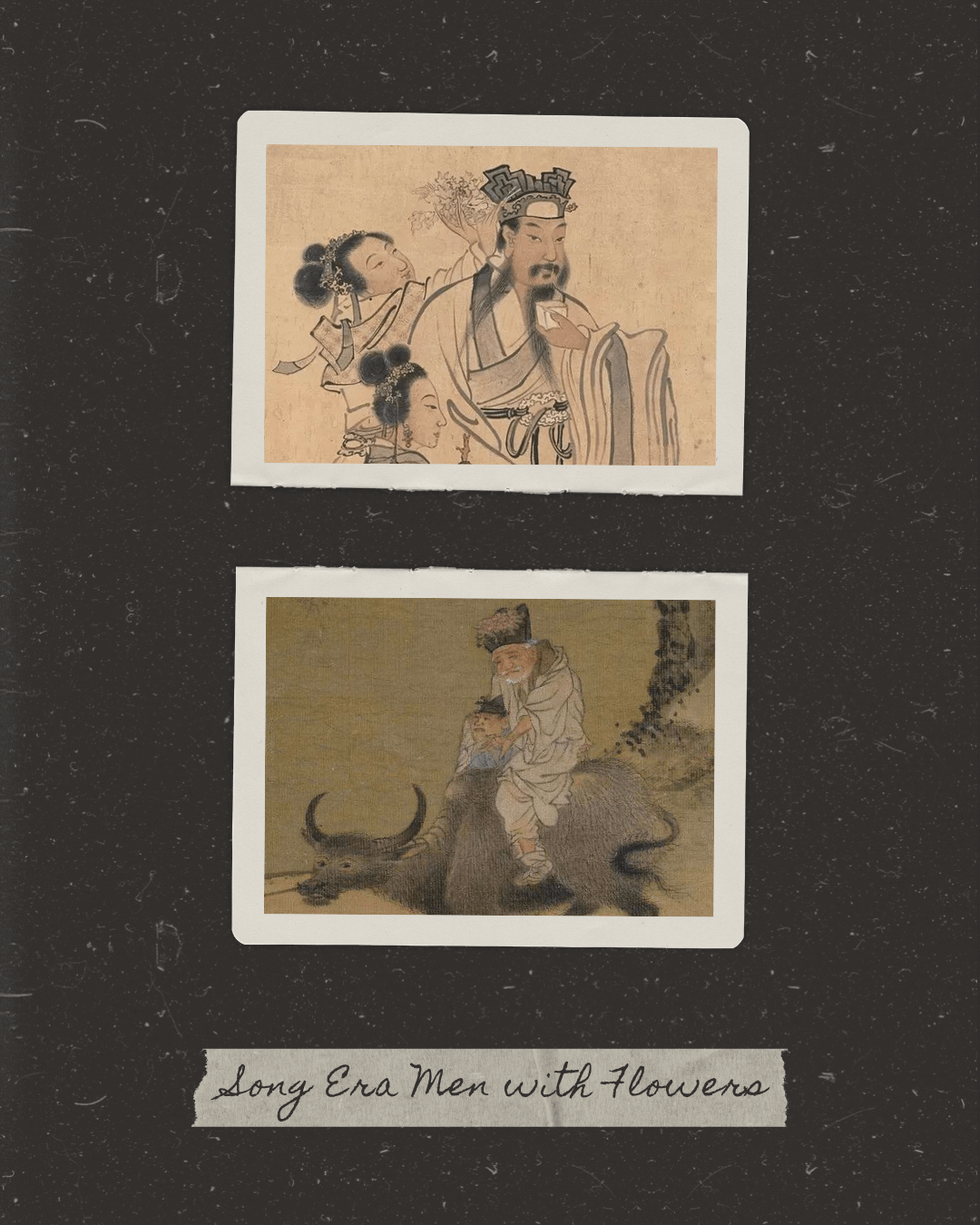

Floral adornments reached their height of popularity in the Song dynasty, driven by commercial prosperity and the rise of the scholar-official elite. Like Xiao Heng and other male characters in the drama, men of the time also wore flowers, fixed in their hair or on headwear, and were even presented with flowers according to rank.

In fact, the drama’s other key source of inspiration for its flower hairpins, Meng Yuanlao’s ‘Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital’ (《东京梦华录》Dōngjīng Mènghuá Lù), records that men wearing flowers was a widespread and common practice:

On the fourteenth day of the first month, when the imperial carriage visited the Five Peaks Monastery, all accompanying officials wore large caps adorned with flowers. On the first day of the third month, at the imperial excursion to Jinming Pool and the Qionglin Gardens, all the palace guards and attendants wore flowers. When the procession returned, the emperor put on a small cap and, with flowers on it, rode on horseback. All the ministers, attendants, and ceremonial guards who accompanied the carriage were granted flowers. After the banquet for the birthday celebrations inside the palace ended, the ministers departed wearing flowers, followed by attendants and guards who were also adorned.

Therefore, both men and women embraced flower hairpins. Renowned Song historian and poet Ouyang Xiu wrote in the ‘Record of Luoyang Peonies’ (《洛阳牡丹记》Luòyáng Mǔdān Jì):

In spring, everyone in the city, regardless of status, wore flowers, even those carrying heavy burdens (春时城中无贵贱皆插花,虽负担者亦然 chūn shí chéng zhōng wú guìjiàn jiē chā huā, suī fùdānzhě yì rán).

During the Tang dynasty, flower ornaments were chiefly made of gauze and silk. By the Northern Song, artisans crafted them from silk brocade and pith to create lifelike, vividly colored blooms. Among the noble and wealthy, they were embellished further with gold, jade, pearls, kingfisher feathers, and tortoiseshell. In the Northern Song dynasty capital of Bianliang, present-day Kaifeng in Henan Province, entire shops specialized in flower ornaments, catering to popular demand.

For more on how floral ornaments shaped Song-era aesthetics, see how zanhua was paired with wusha mao caps and pihong ceremonial attire in ‘Blossom’.

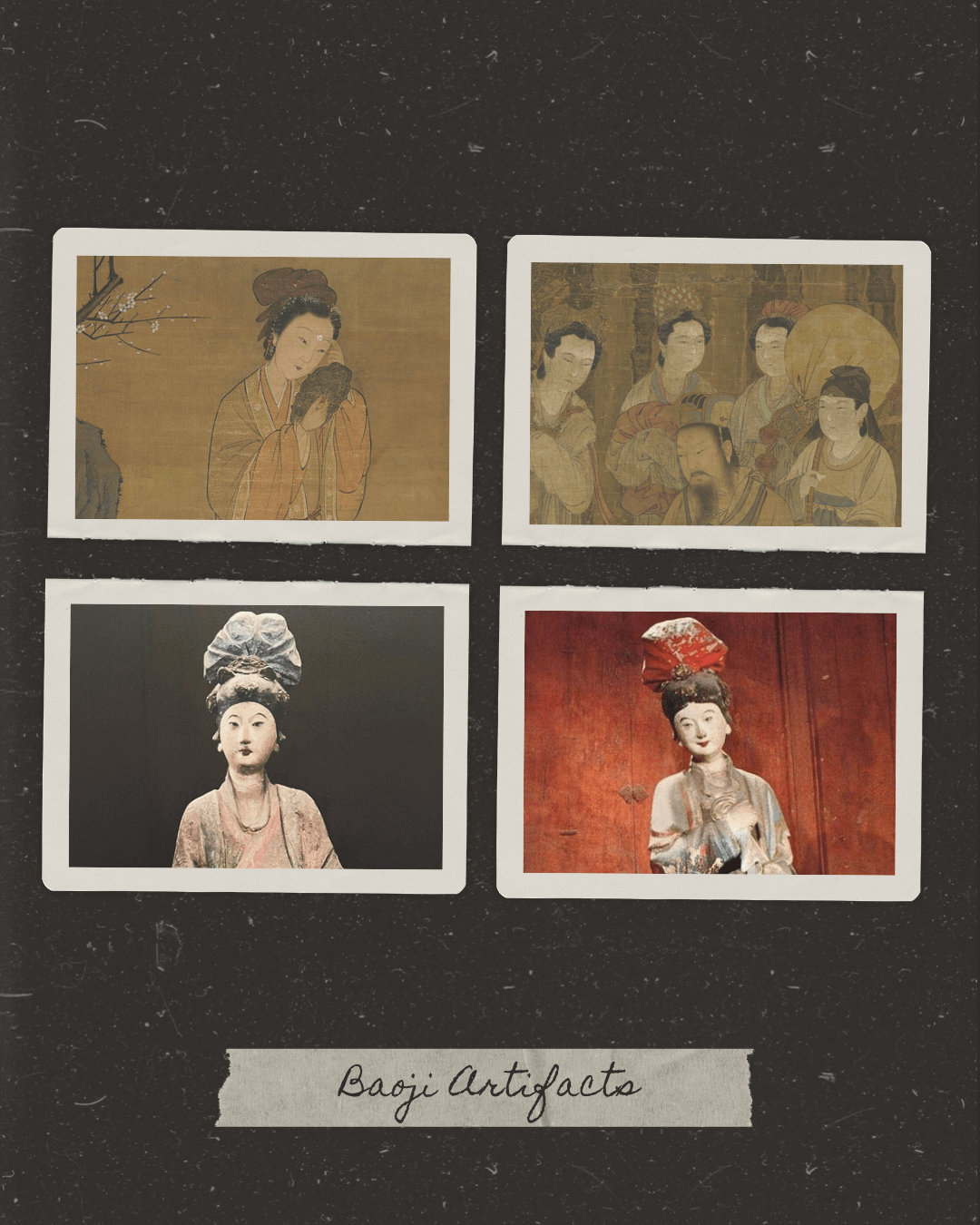

Baoji: Covered Hair Buns

Another striking hairdo in ‘The Double’ is the covered hair bun, white ones with a pearl at the front, worn by Xue Fangfei, Jiang Ruoyao, Liu Xu (Zhao Jiamin) and other female students at school, as well as more colorful versions worn by older ladies including Jiang Li’s grandmother Madam Jiang (Leanne Liu), Ji Shuran (Joe Chen), and Mother Sun (Fan Tiantian).

Was this look inspired by odango buns, hairnets, or chef hats, as netizens have quipped? Actually, the covered hair bun was a popular look for women, as represented in paintings and sculptures across several dynasties.

This covered hair bun, known as baoji (包髻 bāojì), evolved from the jinguo (巾帼 jīnguó) headscarf worn by women during the Han dynasty. Outstanding women of the time were referred to as jinguo yingxiong (巾帼英雄 jīnguó yīngxióng), meaning ‘heroic women,’ because of their headscarves. Later, jinguo itself became a poetic term for 'women.’

By the Song dynasty, baoji had developed into a distinctive fashion as described in Meng Yuanlao’s ‘Dreams of Splendor of the Eastern Capital.’ Women wrapped their hair buns with rectangular silk or cloth scarves, securing them in floral or cloud-like shapes. These bun coverings kept hair clean and tidy while allowing women to look put together at the same time.

Painted sculptures from the Northern Song dynasty at Jinci Temple in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, depict the maids of Yi Jiang, the first queen of the Zhou dynasty, with high buns wrapped in scarves of various colors. Orange, red, blue, and green were especially popular color choices, producing bold and elegant contrast.

The baoji signifies a cultural shift in aesthetic taste, moving from the Tang dynasty’s towering, elaborate hairdos to the Song dynasty’s preference for refined simplicity. These bun coverings could still be adorned with flowers, jewels, and gold ornaments, as seen in the drama, where they are often finished with pearls for an added touch of elegance.

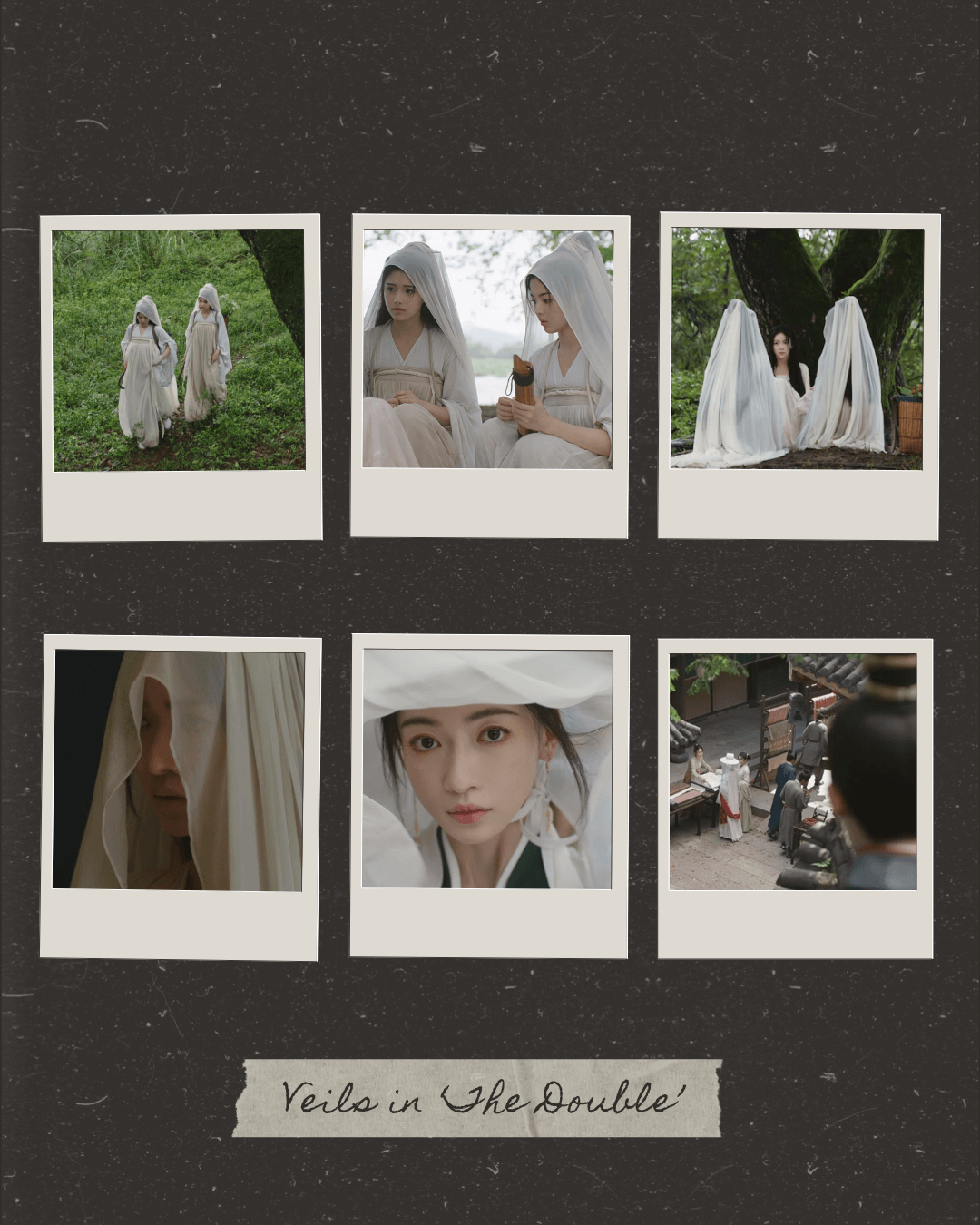

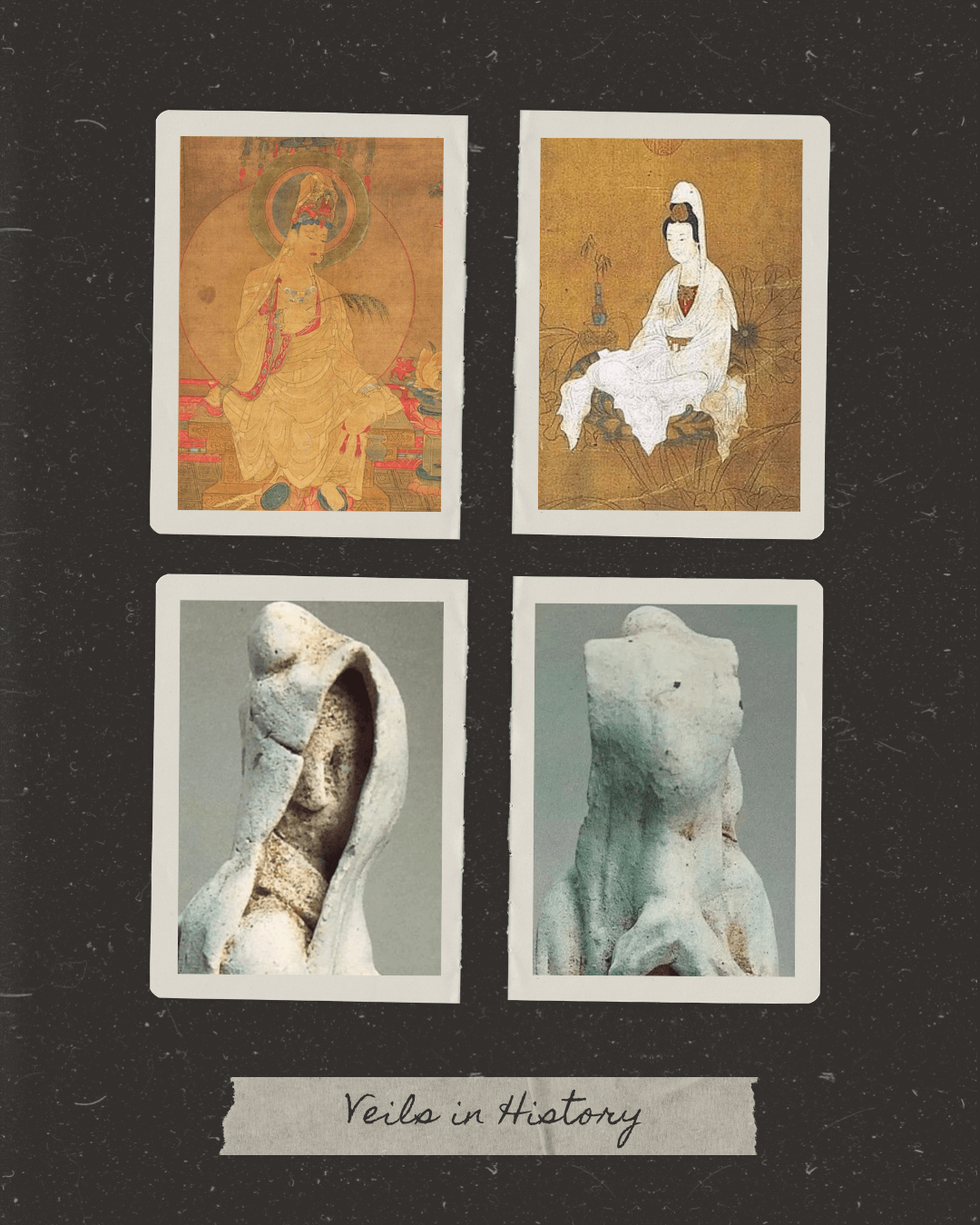

Gaitou: Veils

Some captivating scenes in the drama show Xue Fangfei, Jiang Li, and Tong’er (Ai Mi) wearing flowing white veils that appear to be inspired by the head coverings known as gaitou (盖头 gàitóu) of the Song Dynasty.

Zhou Hui of the Southern Song Dynasty writes in ’Miscellaneous Notes from the Gate of Qingbo’ (《清波杂志》Qīngbō Zázhì) that veils were commonly known as gaitou and were based on the Tang Dynasty ‘veiled hat’ known as weimao (帷帽 wéimào). The gaitou was made from a square piece of gauze that draped down the back, covering half of the body. Women wore these veils when they were out riding or walking in the streets.

As described in the Northern Song poet Liu Yong’s ‘Lychee Fragrance’ (《荔枝香》 Lìzhī Xiāng):

From afar, amidst the crowd, she stands out with her graceful figure.

遥认,众里盈盈好身段。

yáo rèn, zhòng lǐ yíng yíng hǎo shēnduàn.

She seems about to turn her head, yet pauses again by the curtain.

拟回首,又伫立、帘帏畔。

nǐ huíshǒu, yòu zhùlì, lián wéi pàn.

A fair face and rosy brows, glimpsed now and then as she lifts her veil.

素脸红眉,时揭盖头微见。

sù liǎn hóng méi, shí jiē gàitóu wēi jiàn.

With a smile, she adjusts her golden hairpin, her tender heart shining through charming eyes.

笑整金翘,一点芳心在娇眼。

xiào zhěng jīn qiào, yīdiǎn fāngxīn zài jiāoyǎn.

The young lord can only pine in vain, his longing cutting to the bone.

王孙空恁肠断。

wángsūn kōng nèn chángduàn.

This poetic description evokes the moment when Xiao Heng gazes down from the balcony, watching Xue Fangfei in the street below. Her presence catches his eye, just as ‘Lychee Fragrance’ portrays a beauty who stands out to a young lord amidst the crowd. It also parallels a later scene in which Xue Fangfei’s face is unveiled before Xiao Heng, echoing the imagery of the lifted veil in Liu Yong’s lyric poem.

A figurine of a woman excavated from a Southern Song tomb in Poyang, Jiangxi Province, wears a gaitou that covers most of her face and drapes down her back. Similarly, paintings and statues of the goddess Guanyin from the Song dynasty and later periods also feature white gaitou.

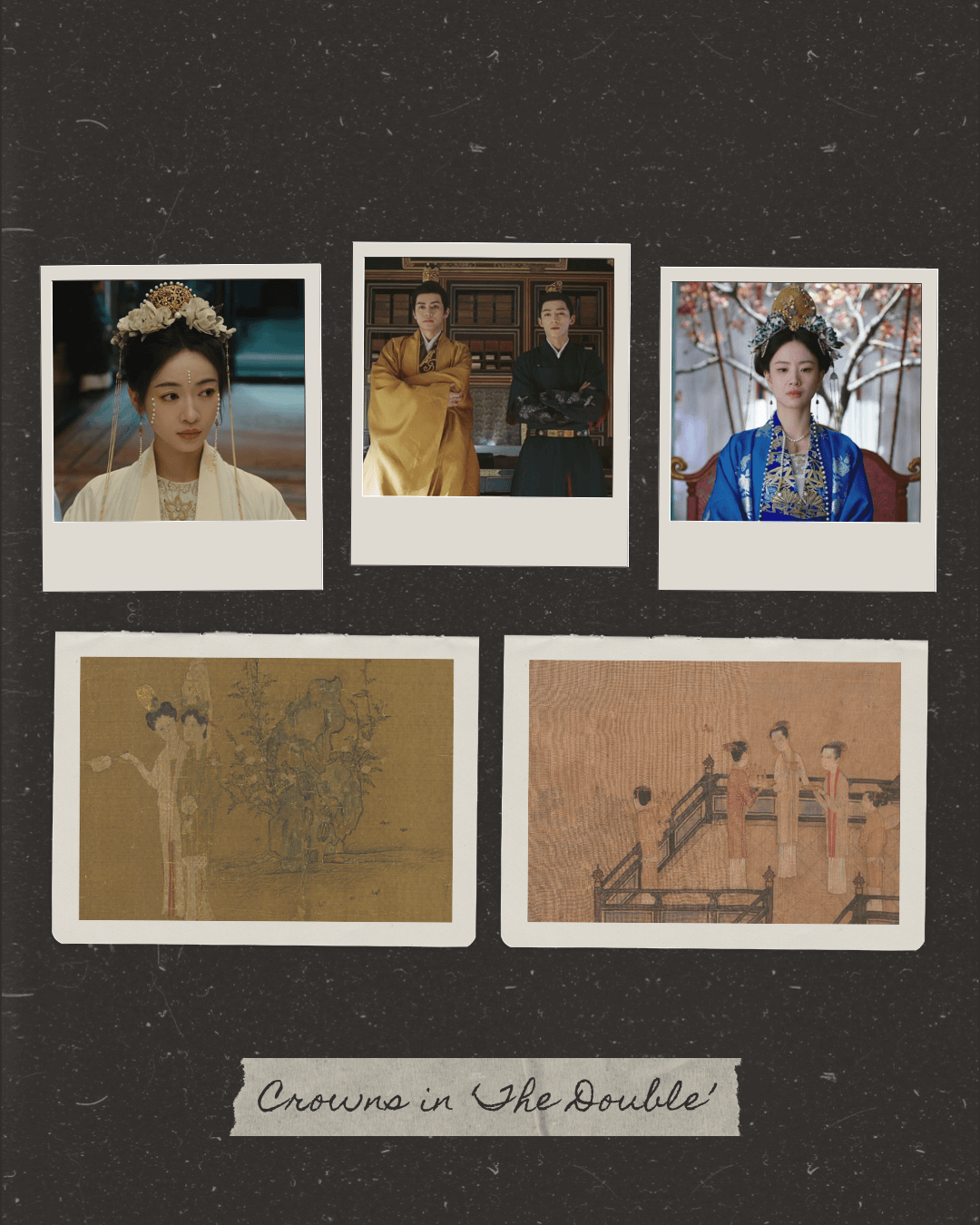

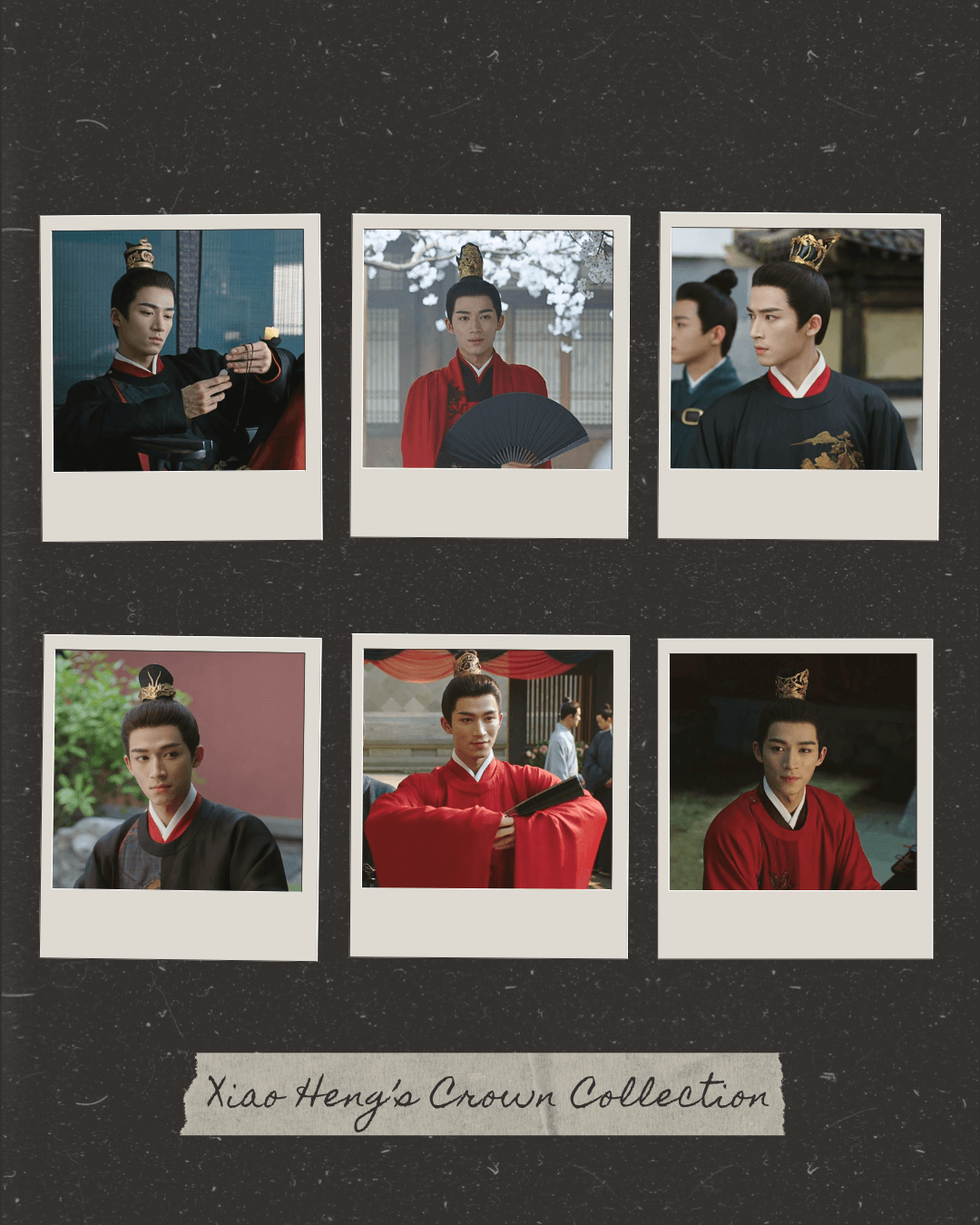

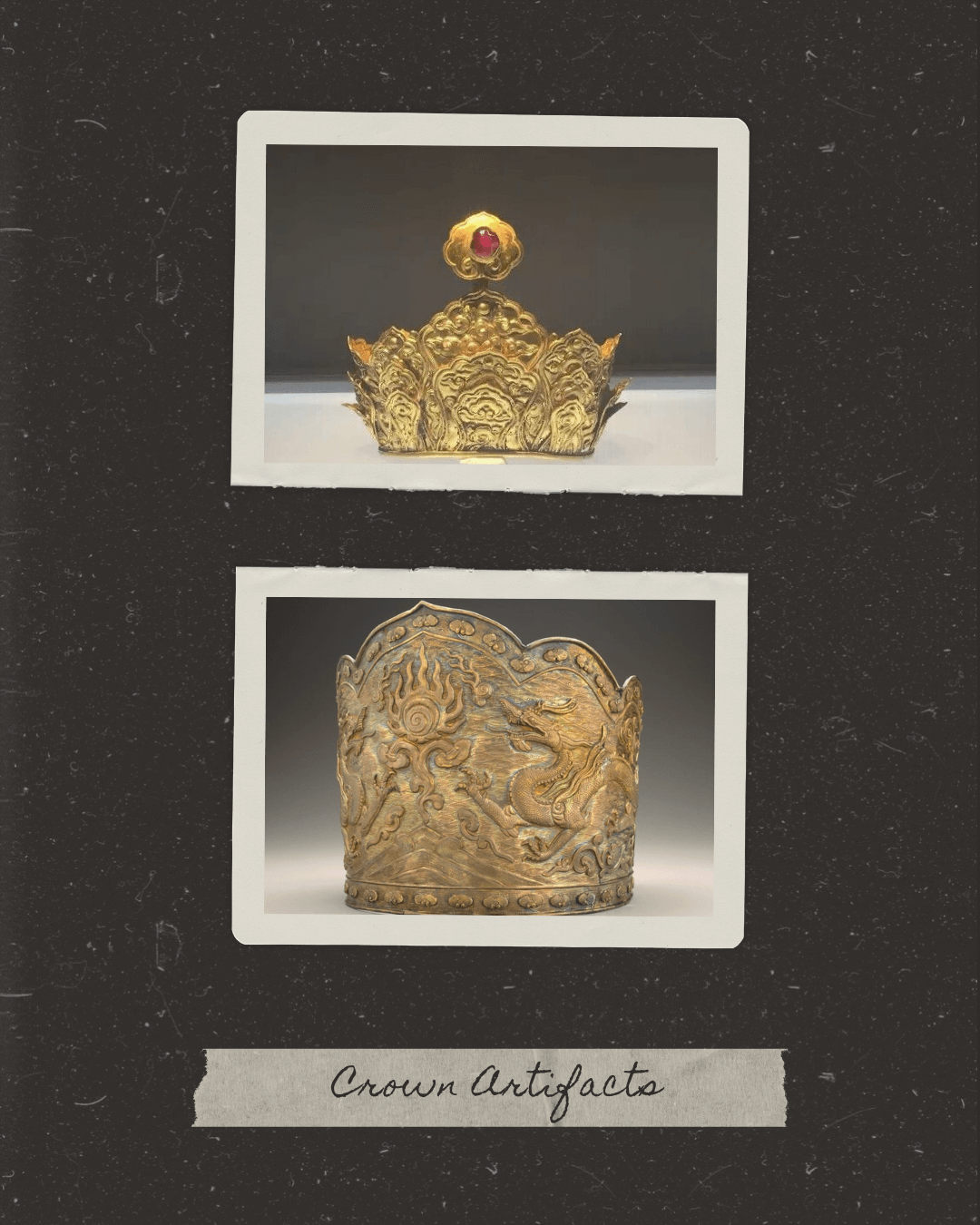

Guan: Crowns

“This time we used a wide variety of guan, including round guan and heart-shaped guan,” shared styling director Song Xiaotao.

The drama indeed features an elaborate assortment of guan (冠 guān), a type of headwear that can be translated as ‘crown,’ worn by both ladies and noblemen, including Xue Fangfei, Consort Li, Princess Wanning, Xiao Heng, and Shen Yurong (Liang Yongqi). Many of their guan are gilded and adorned with pearls and gemstones, incorporating motifs of birds, animals, flowers, and plants.

Princess Wanning and Consort Li wear Song dynasty–inspired styles, including heart-shaped guan (桃心冠 táoxīn guān) and ‘mountain-pass’ guan (山口冠 shānkǒu guān). Notably, Princess Wanning’s signature taoxin guan resembles a golden filigree trinket box inlaid with pearls and gemstones for added opulence.

Meanwhile, Xue Fangfei wears a gilt round guan (团冠 tuán guān) with a floral pattern and a line of pearls along the top.

Xiao Heng wears several different guan throughout the drama, often gilded, set with rubies, and featuring motifs inspired by classical landscape paintings. For example, one of his most distinctive pieces depicts mountains and pine trees with a ruby gemstone at its center. This design heightens his majestic and commanding presence.

Royalty in the Ming and Qing dynasties wore larger gilt guan, inlaid with rubies, that covered the entire head.

Another symbolic guan worn by Xiao Heng features a design of gilded sea cliffs, upon which jeweled wildflowers bloom. Known as ‘lonely fairy grass’ (孤独仙子草 gūdú xiānzǐ cǎo), this plant serves as a fitting symbol for both Xiao Heng and Xue Fangfei, who, like it, grow strong and resilient in harsh conditions.

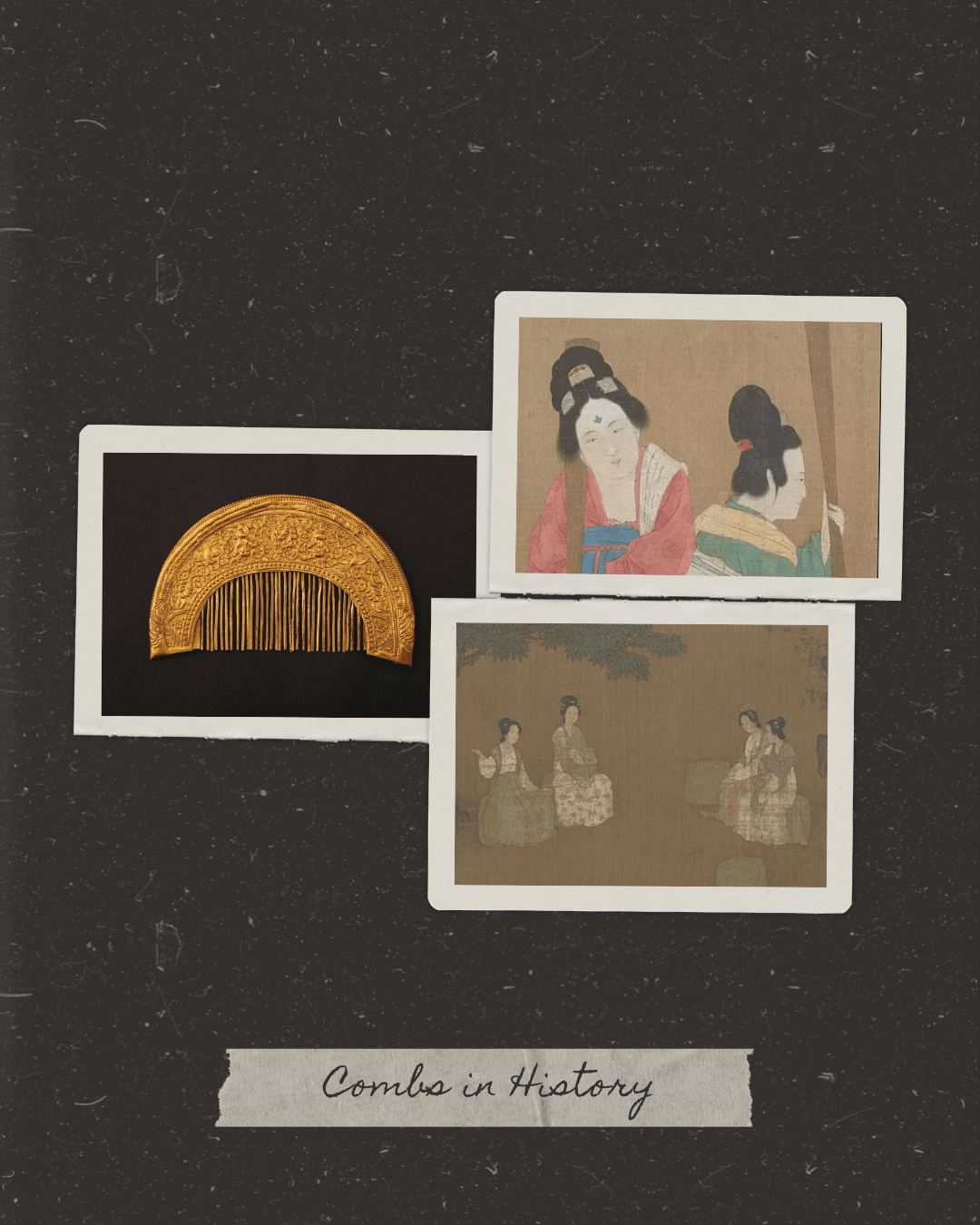

Hair Comb Ornaments

Ladies in the drama, including Ji Shuran, Princess Wanning, Consort Li, and Lu Shi (Zhang Dinghan), wear ornate combs embellished with pearls, placed at the front of the hair bun or on both sides of the head.

Wide-toothed combs were known as shu (梳 shū) and were used for smoothing and styling hair, while those with finer teeth were called bi (篦 bì) and were used to remove dirt and dandruff. By the Tang and Song dynasties, however, combs served not only these practical functions but also became prominent decorative hair ornaments.

Archaeological findings confirm that many combs from these periods featured elongated teeth and were intended more for securing elaborate hairstyles than for everyday grooming. Large combs were especially fashionable during the Tang dynasty, often worn at the front of the head with their teeth facing one another.

Women also wore several smaller combs together in their hair. Tang poet Yuan Zhen captures this fashion in his poem ‘Lament After Dressing’ (《恨妆成》Hèn Zhuāng Chéng) with the line “a full head of little combs” (满头行小梳 mǎn tóu xíng xiǎo shū), reflecting the trend of wearing multiple comb ornaments at once.

Sima You of the Song dynasty gives further detail in his lyric poem ‘Golden Thread’ (《黄金缕·妾本钱塘江上住》Huáng Jīn Lǚ · Qiè Běn Qiántáng Jiāng Shàng Zhù), where he describes “a comb half-emerges from the cloudlike bun” (斜插犀梳云半吐 xié chā xī shū yún bàn tǔ), like a crescent moon peeking from behind clouds of hair.

This style is vividly illustrated in Zhang Xuan’s Tang painting ‘Court Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk’ (《捣练图》 Dǎoliàn Tú) and later in the Song handscroll ‘Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety’ (《女孝经图》Nǚ Xiàojīng Tú) by an unknown artist.

These combs enhanced the size and height of high hair buns, which were especially prized during the Tang dynasty — the bigger, the better. Women often used hairpieces known as ‘fake buns’ (假髻 jiǎjì), made from palm fibers woven onto hemp cloth, to add volume and provide a base for securing large decorative combs.

Chaotian Futou: Heaven-Facing Headwear

This uniquely shaped headwear, worn by the Emperor (Zeng Kelang), has become the focus of memes likening him to the large-eared cartoon character Stitch.

Despite its whimsical appearance, this style of headwear comes from a genuine historical artifact known as the chaotian futou (朝天幞头 cháotiān fútóu), meaning ‘heaven-facing headscarf’. Its distinctive wing-like ribbons, called ‘feet’ (脚 jiǎo), curve upward on either side.

In the ‘Portraits of Successive Emperors and Empresses at the Hall of Southern Fragrance’ (南熏殿历代帝后像 Nánxūn Diàn Lìdài Dìhòu Xiàng), the Later Tang emperor Zhuangzong, Li Cunxu, is depicted wearing a similar futou. According to Bi Zhongxun in ‘Records from Banquets in the Prefectural Judge’s Office’ (《幕府燕闲录》 Mùfǔ Yànxián Lù), the chaotian futou was frequently worn by emperors during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

Headwear with a solid frame, similar to the chaotian futou, developed in the late Tang from the earlier soft cloth futou. The stiffened form gave it structure and elegance, while also making it easier to take on and off like a hat, since it no longer needed to be tied around the head. As a result, the ribbons became primarily decorative rather than functional.

During the Five Dynasties period, emperors favored the chaotian futou, with its upward-curving wings. By the Song dynasty, the futou had become the primary form of official headwear, evolving into a wide range of structured designs with ‘feet’ extending from both sides of the head.

Compared with surviving portraits, the two upturned wings of the emperor’s chaotian futou in the drama are more upright and rounded, giving him a majestic presence while enhancing the design’s visual impact on screen.