A heroine-driven drama chronicling the awakening of a woman determined to rewrite her fate, Blossom emerged as a dark horse hit at the end of 2024. Starring Meng Ziyi and Li Yunrui in leading roles that elevated the careers of both actress and actor to new heights, alongside Kong Xue’er and Xia Zhiguang in memorable supporting roles, the drama is loosely adapted from the web novel ’Nine Layers of Purple’ (《九重紫》Jiǔ Chóng Zǐ) by Zhi Zhi.

Beneath the surface of its adaptation, the drama is, at its core, deeply inspired by the classic novel Dream of the Red Chamber (《红楼梦》Hóng Lóu Mèng) by Cao Xueqin. One of the most celebrated and enduring works of Chinese literature, the novel has been translated into more than 30 languages worldwide, with one of the most famous English translations published in five volumes under its alternative title, ‘The Story of the Stone’ (《石头记》Shítou Jì), translated by David Hawkes and John Minford.

Scriptwriter Jia Binbin and producer Zhang Yingying have shared that the drama’s writing and production teams intentionally incorporated references and parallels to ‘Dream of the Red Chamber’ into ‘Blossom’ while reinterpreting its themes for modern audiences. The result is an empowering story centered on a heroine who takes control of her narrative and forges her own path forward.

To further lean into the drama’s elegant, meditative tone and atmospheric setting, the writing team dug into classical texts and embedded references to famous lines of classical poetry throughout the script, particularly from the great Tang poets.

Meanwhile, Zhi Zhi, author of the original source material, has spoken about how rereading ‘Dream of the Red Chamber’ as an adult gave her a deeper appreciation for the classic novel, particularly from a writer’s perspective:

The book doesn’t just contain a love story — it also depicts ancient food culture, social customs, workplace dynamics, and family power struggles. Using the four seasons as a narrative thread, it weaves together countless vivid scenes, tracing the rise and fall of a once-prosperous family. The writing techniques are incredibly sophisticated and masterful, allowing me to gain invaluable insights. I suddenly understood why some people dedicate their lives to reading and studying ‘Dream of the Red Chamber.'

Here’s a look at the most striking ways the drama channels one of the four great classic novels of Chinese literature, whilst arriving at its own conclusion from a distinctly female perspective. It reframes thematic devices that once foreshadowed tragedy as a sliding doors moment, drawing on lived experience to throw open the possibility of altering what lies ahead.

Records and Verdicts

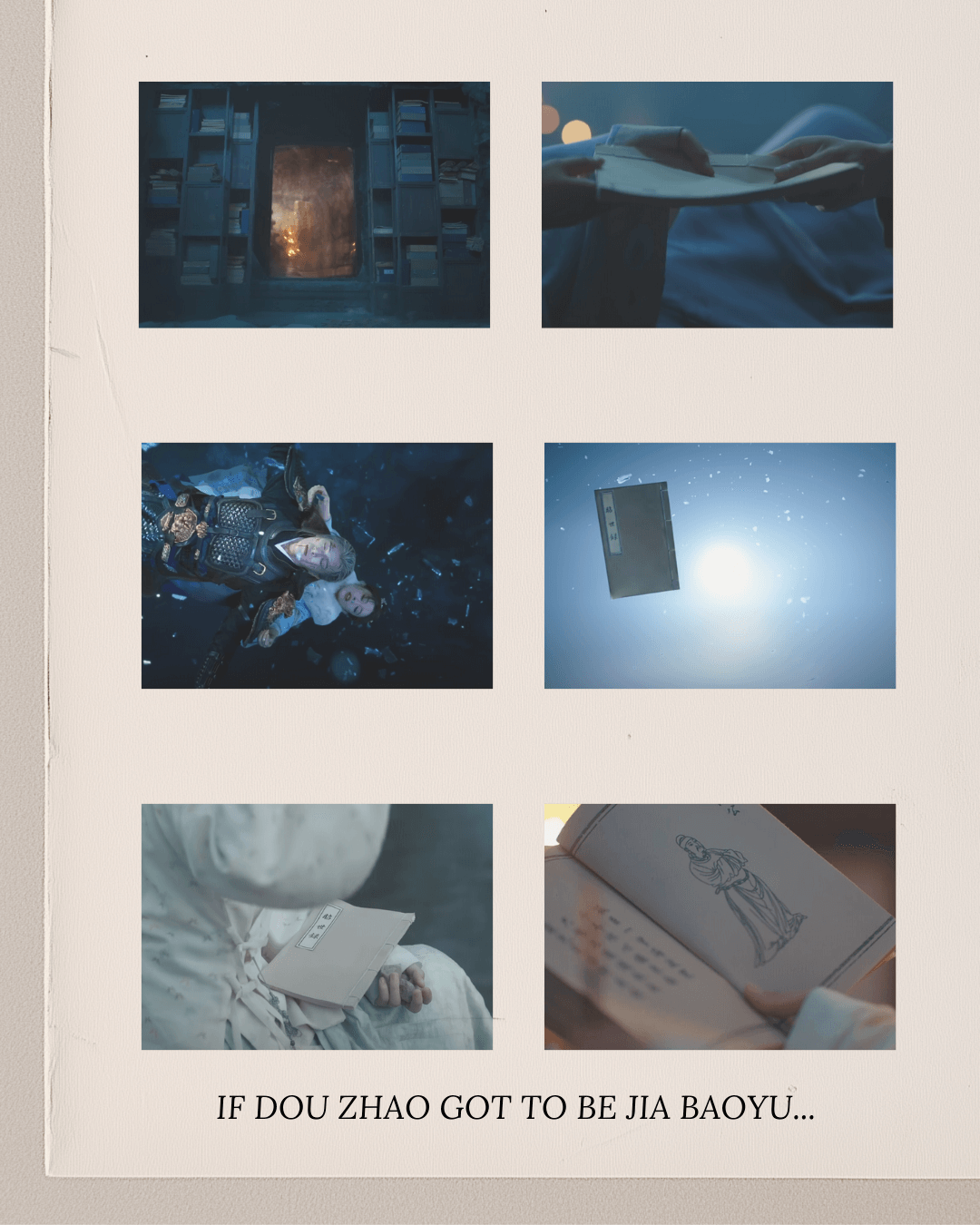

When crafting the script, Jia Binbin envisioned Dou Zhao (Meng Ziyi) as a reimagined Jia Baoyu, the sensitive “soft boy” protagonist of ‘Dream of the Red Chamber.’ In the classic, Jia Baoyu dreams his way into the Land of Illusion (《太虚幻境》Tàixū Huànjìng) while napping during a garden party. There, he visits the Department of the Ill-fated Fair (《薄命司》Bómìng Sī), a celestial bureau where the verdicts of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling are catalogued — each paired with a cryptic poem and illustration foretelling their fates. These prophecies speak of abuse, social ruin, and death. Yet Baoyu, reading them to the end, fails to grasp their true meaning and remains a passive witness.

With ‘Blossom,’ Jia Binbin poses the question: “If Dou Zhao were like Jia Baoyu and accidentally entered the Land of Illusion but actually understood the verdicts, would she try to change the fates of her family and everyone around her?”

And on that note, Dou Zhao is sent falling through a dream of her tragic life into the next life, armed with the ‘Records of the Enlightened Age’ (《赵实录》Zhào Shílù), also directly translated as the ‘Veritable Records of Zhao.’ This mystical book lays bare the fates of both men and women in her social sphere.

Poignantly, Dou Zhao reflects: “This entire life, not even for a moment, has ever been mine to choose.”

She then recites these lines from Tang Dynasty poet Bai Juyi’s ‘The Road to Mount Taihang’ (《太行路》 Tàiháng Lù):

In life, one should not be born a woman,

a hundred years of suffering and joy dictated by others.

Subverting the Verdicts

In a preface to ‘Dream of the Red Chamber,’ author Cao Xueqin sheds light on his intention to write a tribute to the young women he had known in his youth. Looking back, he recognized them as “morally and intellectually superior” to the man he had become, yet still voiceless and unacknowledged. Determined not to “allow those wonderful girls to pass into oblivion without a memorial,” he sought to preserve their existence in fiction.

While the classic novel mourns the tragic fates that befall its women despite their talent, personality, and potential, ‘Blossom’ portrays a world where a woman can reclaim her narrative and prevent history from repeating itself.

The drama imagines a protagonist with the foresight to alter her fate and the fates of those around her. Placing the ‘Records of the Enlightened Age’ in Dou Zhao’s hands symbolically grants her knowledge and agency traditionally reserved for men, overturning the dynamic in which Jia Baoyu alone was chosen to read the fates of the women around him, fates that they themselves were never allowed to see.

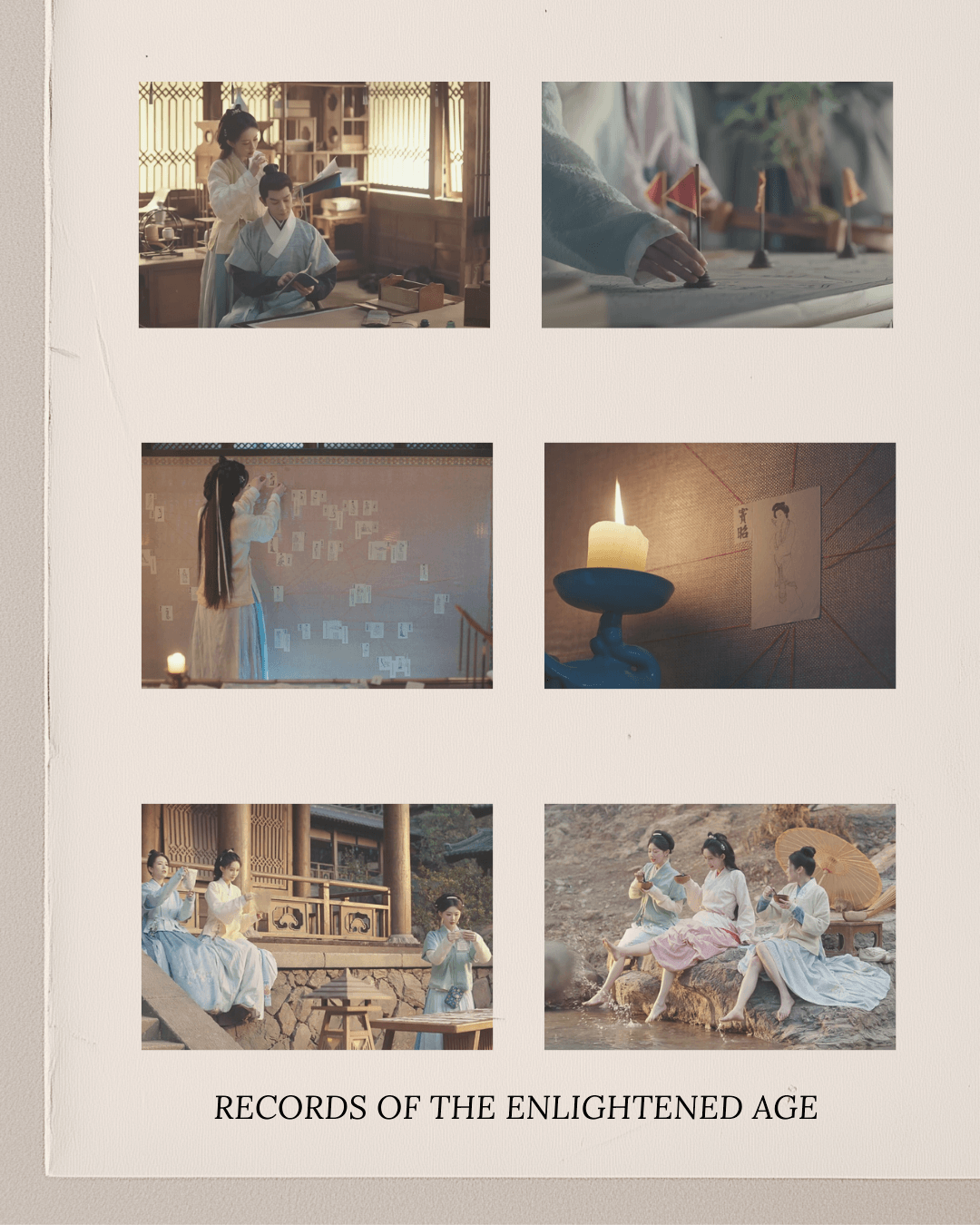

Dou Zhao finds a way to escape the messy scandals of the Dou family mansion and grows up in the countryside with the kind and resilient Granny Cui (Mu Liyan) as her guardian. There, she studies literature, learns the ways of business, and trains in medicine under the tutelage of Ji Yong (Xia Zhiguang), honing an impressive trifecta of entrepreneurial, deductive, and problem-solving skills along the way.

In turn, she empowers her friends, including Miao Ansu (Kong Xue’er), to achieve financial independence, while her partner, Song Mo (Li Yunrui), gives support without encroaching on her autonomy.

By paralleling and then subverting the inescapable nature behind the fates of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling in ‘Dream of the Red Chamber,’ the drama ‘Blossom’ establishes Dou Zhao as a proactive, capable heroine within a period setting.

Karmic Bonds and Intertwined Fates

Both ‘Dream of the Red Chamber’ and ‘Blossom’ tell stories of characters whose karmic bonds, forged through past-life encounters, lead to deep entanglements in their present lives. Inspired by Buddhist ideas of reincarnation and transmigration, these stories depict how past acts of kindness, sacrifice, and salvation transcend lifetimes, drawing souls back together to resolve unfinished business.

In ‘Dream of the Red Chamber’, the protagonists Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu share a passionate bond rooted in their past-life connection in the heavenly realm. Lin Daiyu is the reincarnation of a flower from paradise, which Baoyu, in his form as a divine stone, watered with celestial dew. Eternally grateful, she vows to repay his kindness with a lifetime of tears in the mortal world. Baoyu’s act of service puts Daiyu into karmic debt, binding her to him in a star-crossed romance marked by sorrow and longing as they navigate the trials of their human existence.

In a similar vein, ‘Blossom’ traces Song Mo’s repeated efforts to save Dou Zhao in a previous life. On the third attempt, he fails to block an incoming arrow, and they are both hurled through the ether into a cycle of rebirth. Falling into the void together, their fates intertwined, a drop of Song Mo’s blood lands behind Dou Zhao’s ear, forming a birthmark shaped like three petals — a physical reminder of their karmic bond.

When they find each other in the next life, arrows come for Dou Zhao once more, triggering the trauma from her past life as she fights to change her fate amid repeated brushes with death. This time around, she survives each encounter, and astonishingly, the three-petaled blood birthmark behind her ear vanishes. By deciphering the ‘Records of the Enlightened Age’ and taking fate into her own hands, Dou Zhao manages to wipe her slate clean.

While Cao Xueqin depicts Lin Daiyu suffering quietly in his novel, lamenting that Baoyu “can do nothing to alter my fate,” Dou Zhao takes decisive action to change not only her fate but Song Mo’s as well, subverting the “damsel in distress” trope. Song Mo may protect and defend Dou Zhao, but she also pulls him back from the brink of his fate, lighting up a different path for him in his darkest moment.

Their karmic bond is redefined as an equal partnership built on teamwork and mutual understanding. As Dou Zhao tells Song Mo, “I won’t be a good wife, but I will be a good partner.”

Dreams and Mirrors

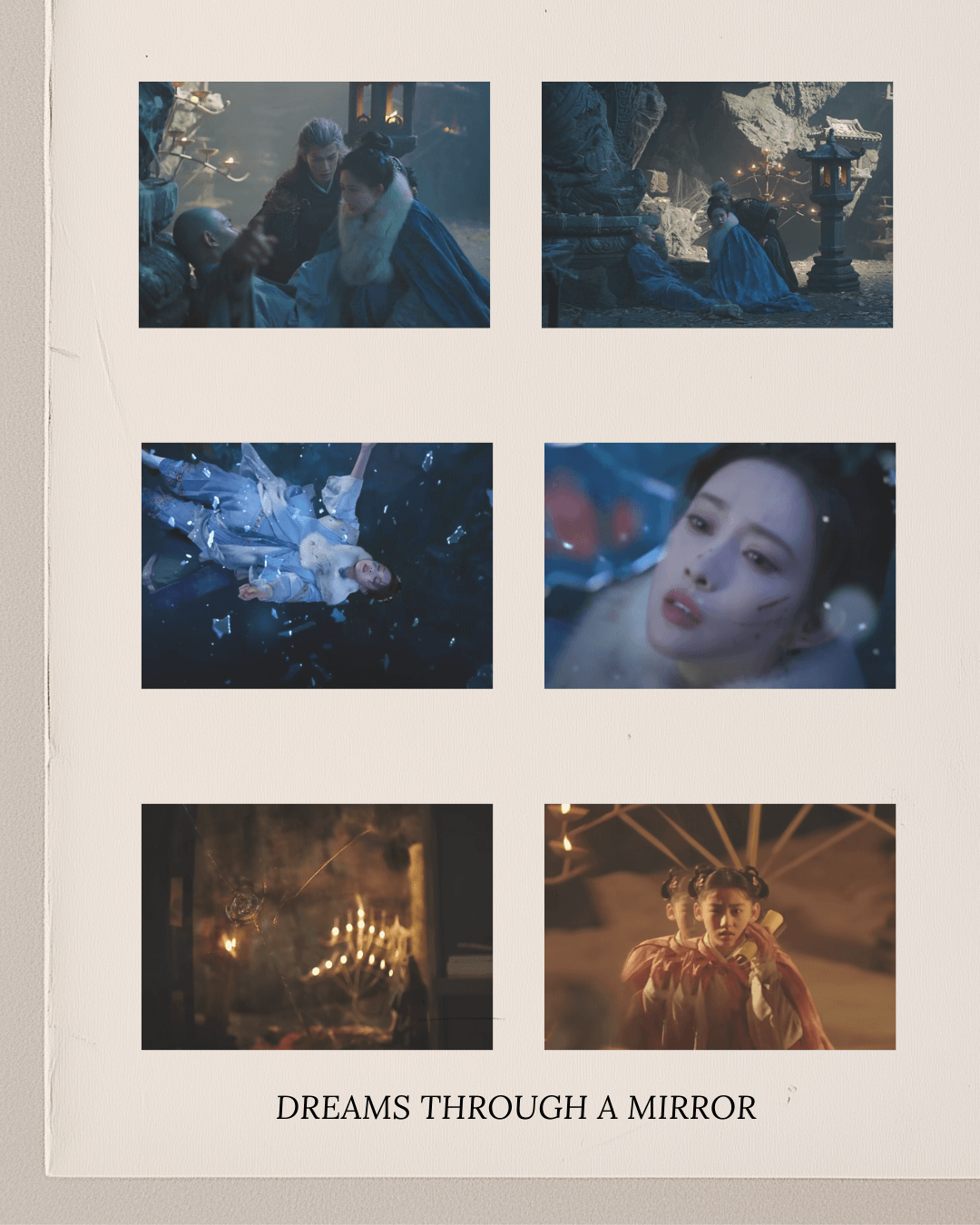

‘Blossom’ draws from the imagery of dreams and mirrors in ‘Dream of the Red Chamber’ by framing reincarnation as two realms on either side of a mirror.

After experiencing a tragic life, Dou Zhao falls through an abyss of shattered glass, each fragment reflecting moments from her past. She awakens as a young version of herself, played by Liu Jiaxi, before a bronze mirror, where Yuan Tong, now a young Ji Yong (Yang Jingtian), reveals that she was knocked out after striking her head on the mirror while immersed in a book. This book, ‘Records of the Enlightened Age,’ said to be a playbook left by its author for a destined person (有缘人 yǒu yuán rén), recounts her previous life — or perhaps a life she only dreamed she had lived after becoming too deeply immersed in its pages.

This moment parallels that pivotal scene in ‘Dream of the Red Chamber,’ where Jia Baoyu naps in a room with a mirror once belonging to Empress Wu Zetian and is transported to the Land of Illusion to read the records on the fates of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling. At its entrance, an inscription reads:

Truth becomes fiction when the fiction’s true;

Real becomes not-real where the unreal’s real.

‘Dream of the Red Chamber’reminds us that the boundaries between reality and illusion, truth and fiction, are fluid and porous. According to the classic novel, we exist in a realm where the “reader's tears” evoked by fiction can feel “more real than human life appears” and “life itself is a dream.” Relatable, much?

‘Blossom’ follows in the footsteps of this classic, casting the mirror as a portal between truth and fiction, past and present, dreams and reality. Through this intertextual nod, the drama suggests that Dou Zhao’s dream would be just as valid as a lived existence.

This idea is reinforced through the parting words of the monk Yuan Tong (Xia Zhiguang) in Ji Yong’s previous life, or dream:

Hidden within misfortune lies fortune;

Cause and effect are intertwined.

Yuan Tong’s statement echoes the inscription at the gateway to the Land of Illusion while offering a new perspective: that Dou Zhao can find fortune on the flip side of misfortune and change her fate through her own actions.

Flowers and Courtyards

Both ‘Blossom’ and ‘Dream of the Red Chamber’ use floral imagery and symbolism to reflect life and embody human qualities.

The classic novel unfolds within the Grand View Garden (大观园 Dàguānyuán), a meticulously constructed sanctuary that is ultimately destroyed. Within the garden, Baoyu and Daiyu, along with the other beauties of Jinling, form poets’ societies named after flowers. The Haitang Poets Society (海棠诗社 Hǎitáng Shī Shè) is an ode to the haitang flower, also translated as crab-flower, crabapple flower, or begonia, as seen in the English titles for the Chinese drama Winter Begonia and the animated film Big Fish & Begonia. Later, it was succeeded by the Peach Blossom Society (桃花社 Táohuā Shè).

The inner courtyard of the Dou mansion in the drama bears a resemblance to the Grand View Garden in its intricate construction. Zhang Meng, who plays Dou Zhao’s stepmother Wang Yingxue, takes us behind the scenes in a vlog, revealing how these courtyards were meticulously built on sound stages, underscoring their realistic façade and the controlled nature of these traditionally female spaces. Like the Grand View Garden, the drama’s inner courtyard is a place where women, like flowers, are cultivated for admiration yet ultimately stifled within the garden walls.

In the inner courtyard, Dou Zhao’s mother (You Jingru) is likened to her favorite flower, the magnolia — dignified, beautiful, and pure — devoting herself to her husband, Dou Shiying (Ji Chenmu). But when he betrays her and orders the flowers of her magnolia tree beaten down for his new wife, her fate follows the falling magnolia blossoms, destroyed before their time.

This idea is deeply rooted in ‘Dream of the Red Chamber,’ where women are likened to flowers, symbolizing beauty and fragility, their blooms inevitably sullied by the world around them, and even destined for death as soon as they bloom. When Baoyu idly tosses fallen petals into the stream, Daiyu stops him, remarking that the water will carry them to “muck and impurity.” She gathers the petals in a silk bag and lays them to rest in a “flower grave.”

Yet, ‘Blossom’ also characterizes flowers as resilient and enduring. Granny Cui takes a young Dou Zhao beyond the confines of the inner courtyard and into the countryside, telling her:

“If you remain confined to the petty rivalries of the inner courtyard, you will grow narrow-minded and stunted. In the future, you will only scheme within the limits of four walls and never see the vast world beyond. I want your brilliance to step out beyond the confines of the household, to reach the mountains, rivers, lakes, and seas, the nation, the world under heaven. That is where you will truly shine."

Granny Cui introduces Dou Zhao to the ‘Nine-layered Purple’ (九重紫 jiǔ chóng zǐ), a poetic name for the wisteria sinensis flower and a nod to the title of the source novel. Granny explains that, unlike peonies and orchids, this purple blossom “doesn’t need perfect conditions, nor a favorable time or place — scatter its seeds, and it will climb and spread across the mountains on its own.”

Dou Zhao aspires to be “like the ‘Nine-layered Purple,’ strong and resilient, able to withstand the wind and rain.” She declares: “From now on, I want to live well for myself.”

Staying true to her vow, Dou Zhao becomes a successful businesswoman, and like the unyielding purple blossoms around her, climbing toward the sky, she flourishes with her best friends, Miao Ansu and Zhao Zhangru (Liu Meitong) by her side.

‘Blossom’ brings the story full circle, showing her mother’s once-beaten magnolias blooming again in full glory. Dou Zhao stands beneath their canopy with Song Mo, having found a love that is right for her, built on equality and mutual respect.

Details in Handwriting

Lin Daiyu of ‘Dream of the Red Chamber’ and Dou Zhao of ‘Blossom’ both deliberately omit strokes when writing their late mother’s names as a quiet yet heartfelt gesture of mourning.

Daiyu refrains from fully forming the character min (敏 mǐn), and her tutor, Jia Yucun, discovers the reason behind this habit upon learning of her mother’s passing:

I have often wondered why it is that my pupil Daiyu always pronounces min as mi when she is reading and, if she has to write it, always makes the character with one or two strokes missing. Now I understand.

This is mirrored in the drama when Dou Zhao’s sister, Dou Ming (Li Baihui), Wu Shan (Quan Yilun), Ji Yong, and Song Mo individually attempt to help her complete a punishment of copying texts. While Ji Yong comes close to imitating her handwriting and produces passable copies, only Song Mo captures her script perfectly, down to the tiny detail that all the others miss: Dou Zhao deliberately omits a stroke in the character qiu (秋 qiū), meaning autumn, a part of her late mother’s name.

This subtle detail marks a shared understanding and a private ritual that transcends words, carried in the spaces between the strokes, and in the smallest yet most intentional of actions.

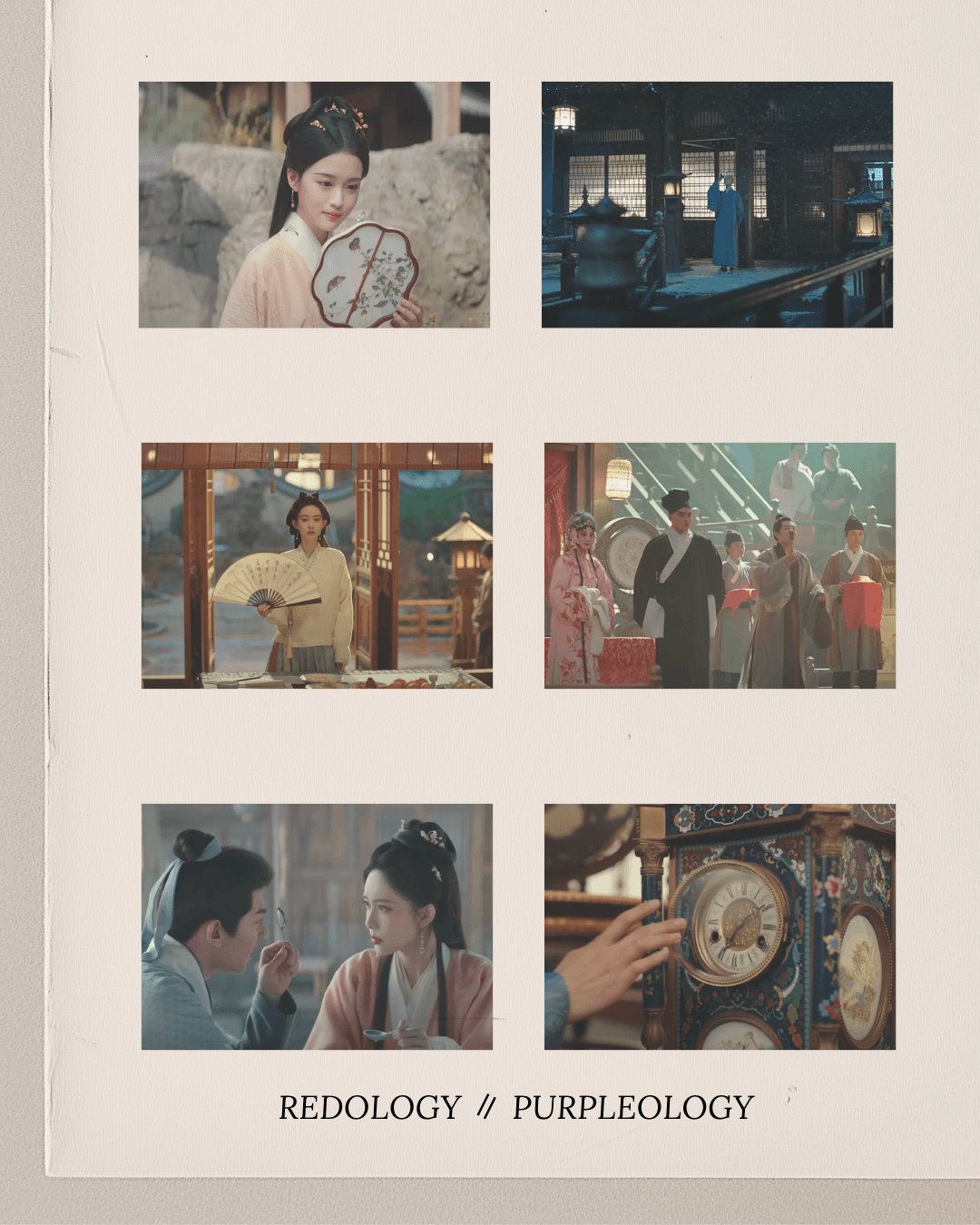

‘Redology’ Meets ‘Purpleology’

‘Redology’ is a somewhat affectionate term, familiar to both devoted readers of the classic novel and scholars alike, for the vast body of literary scholarship devoted to ‘Dream of the Red Chamber.’ It encompasses everything from questions of authorship and historical context to the novel’s expansive cast, rich symbolism, and philosophical viewpoints. Over the centuries, the novel has inspired much lively commentary and debate, a testament to the work’s enduring place in both the Chinese and global cultural imagination.

Following in this tradition, I’ll use the term ‘Purpleology’ to describe the close reading and analysis of ‘Blossom,’ particularly in relation to ‘Dream of the Red Chamber.’

The drama engages closely with the classic, staging many of the iconic and memorable images from the novel to craft a layered, intertextual response. These include catching butterflies on a fan, guessing hidden objects from riddles, writing poetry at dinner parties, displaying foreign-imported objects such as clocks and eyeglasses, watching operas and plays that foreshadow unfolding events, and featuring Buddhist monks and wandering Daoists as enigmatic guides.

These recognizable details pay tribute to one of China’s most remarkable literary masterpieces while enriching ‘Blossom’s’ visual storytelling, allowing audiences to experience, or perhaps rediscover, the poetic and philosophical brilliance of ‘Dream of the Red Chamber’ through a fresh, empowering lens.

Wheel of Fate to Flywheel Effect

While ‘Blossom’ evokes the tone, themes, and imagery of ‘Dream of the Red Chamber,’ adding a delicious layer of nuance for audiences to savor, it reimagines these elements through a modern narrative of agency and self-determination.

This is seen in Dou Zhao’s story as her actions transform the wheel of fate into a flywheel of growth and progress. Her rise as a successful businesswoman embodies the flywheel effect, an entrepreneurial concept where small, consistent efforts compound into unstoppable momentum. She literally takes the wheel in her own hands, refusing to let fate steer her course.

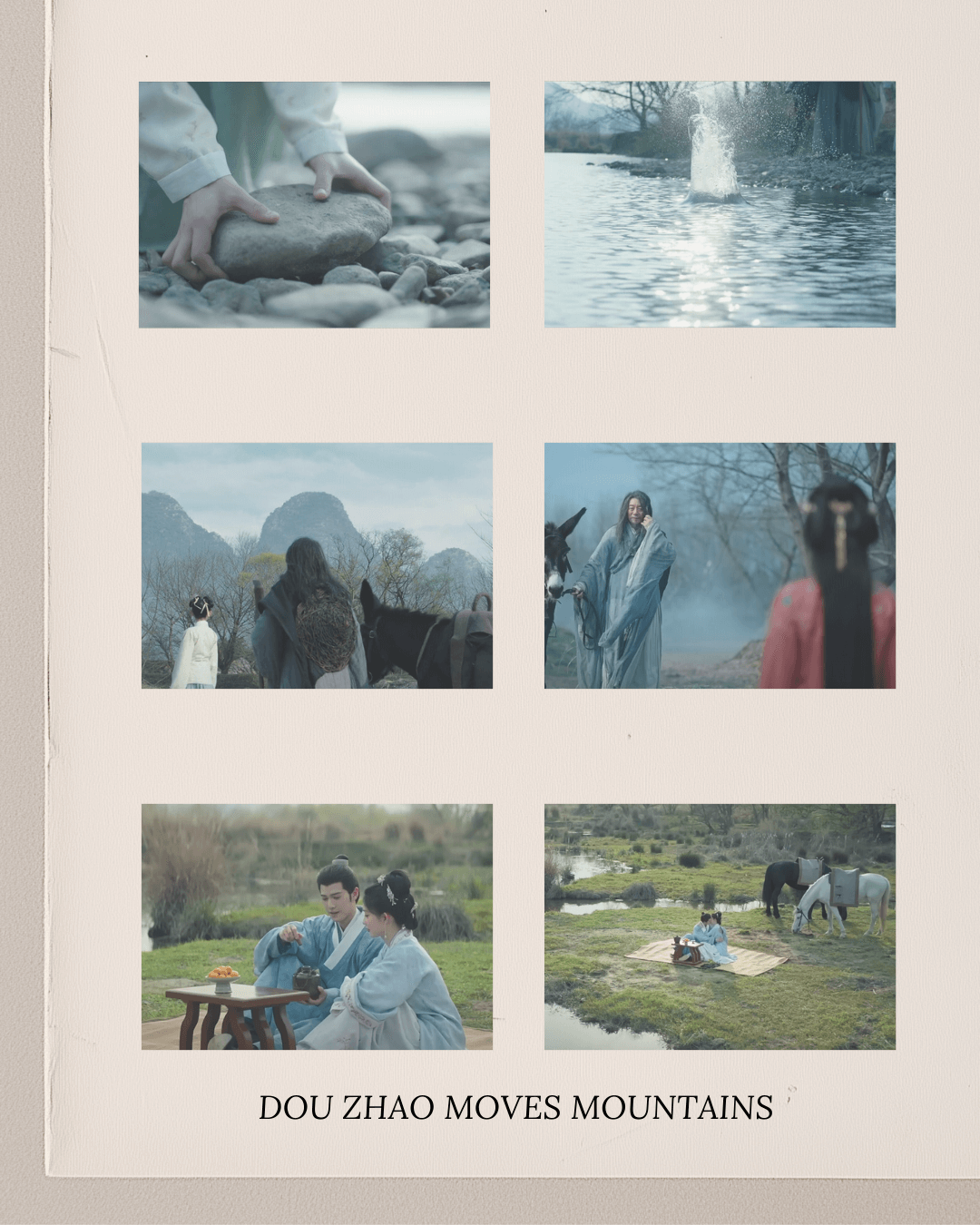

When confronted with the enormity of her mission, which the drama likens to moving mountains, Dou Zhao chooses perseverance, echoing the Chinese fable ‘Yu Gong Moves Mountains’ (《愚公移山》Yú Gōng Yí Shān). In the tale, an old man’s seemingly insurmountable task earns only ridicule until the gods, moved by his conviction, intervene to help. Initially overwhelmed by the scale of her own challenge, Dou Zhao drops metaphorical stones into the river of life, and step by step, she shifts its course and paves a new path.

Fittingly, ‘Blossom’ itself defied expectations, becoming an unexpected hit at the tail end of the year and propelling its stars, Meng Ziyi and Li Yunrui, into the spotlight. In less than a year, they have signed on to film their second drama together, Tiger Sniffs the Rose (《尚公主》Shàng Gōngzhǔ), or directly translated as 'Princess Shang,' adapted from the web novel of the same name by Yi Ren Kui Kui.

Both have remarked that their hard work over the years, along with making the best of every opportunity, has led to this moment and opened up more choices in their careers today.

“It’s made me believe even more that there is meaning in my efforts,” says Meng Ziyi.

Li Yunrui, whose formative years as an athlete shaped his life philosophy, echoes this sentiment.

“Consistent effort pays off,” he says. “Don’t be quick to say ‘I give up,’ and maintain your confidence in yourself.”

While honoring the poetic and philosophical brilliance of ‘Dream of the Red Chamber,’ ‘Blossom’ reframes its themes for a modern audience, reminding us that even when the odds are stacked against us, what matters is having the courage to grow beyond the walls that confine us and block the view of the vast world of possibilities beyond.

And even if we are merely a single drop in the vast ocean of history, no matter what others say, and how much sense they seem to make, our lives are still ours to live, and our hearts are ours to follow.