Chinese costume drama The Glory, starring Chen Duling and Xin Yunlai, has emerged as a dark horse hit, captivating audiences with its female-led revenge narrative, evocative cinematography, and meticulously crafted period setting, inspired by the Ming dynasty.

“We had many discussions with our production designer about the Humble Administrator’s Garden in Suzhou,” says director Yang Long in a behind-the-scenes special for the drama.

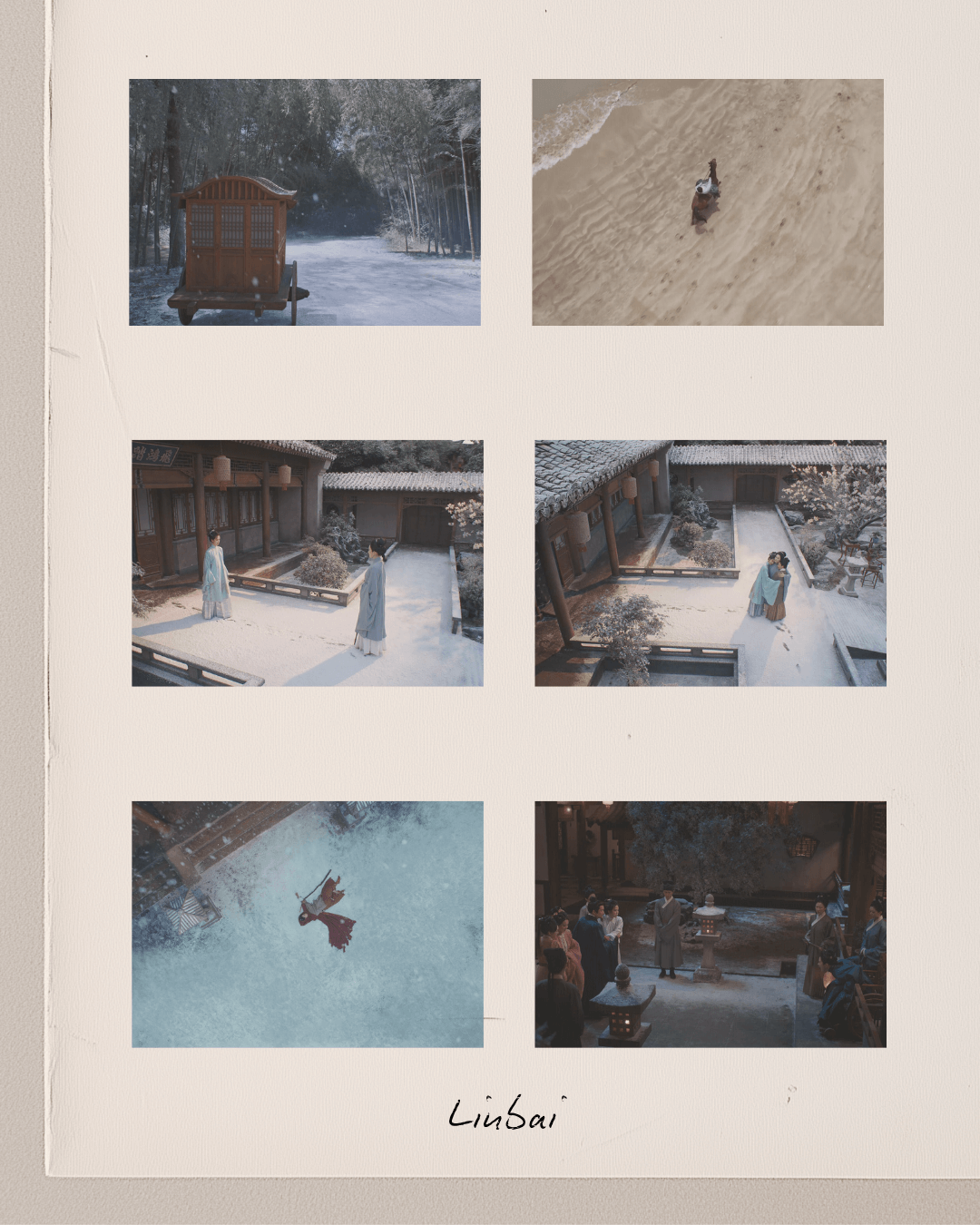

“Our visual style balances abstraction in the big picture with realism in the small details,” adds production designer Wang Yifan.”We drew inspiration from the art of liubai in Suzhou gardens to give the scenes an ethereal sense of beauty.”

The Humble Administrator’s Garden (拙政园 zhuōzhèng yuán), mentioned by the drama’s director, was built in Suzhou during the Ming dynasty by Wang Xianchen, a disillusioned scholar-official. The garden embodies the principle of leaving intentional blankness, known as liubai (留白 liúbái), in its design.

The intentional use of blank space found throughout classical Suzhou gardens invites introspection and interpretation from the visitor, while reflecting the pursuit of harmony between humans and nature. They express the philosophical ideals of the Chinese literati, shaped by Daoism, Confucianism, and Zen Buddhism, known in Chinese as Chan Buddhism (禅宗 chánzōng).

One of the most influential texts on Chinese garden design is ‘The Craft of Gardens’ (《园冶》 Yuányě), written in the late Ming dynasty by Ji Cheng of Wujiang, located in present-day Suzhou. This classic has had a lasting impact on East Asian architecture and design, continuing to inspire artists and designers internationally to this day.

Ji Cheng devotes the final chapter of his book to the concept of jiejing (借景 jièjǐng), meaning ‘borrowed scenery’. This borrowing can take many forms — drawing on views and objects near or far, above or below, as well as qualities from the surroundings, such as season, light, and color — and incorporating these elements into the experience of a garden or space.

Here’s a closer look at how ‘The Glory’ draws on the principles and compositional techniques from classical Chinese garden design, including liubai and jiejing, to build mood, evoke emotion, and create meaning onscreen.

Liubai: Leaving Blank Space

Liubai (留白 liúbái), leaving a space blank, or literally white (白 bái), shapes the composition of many memorable scenes in the drama, giving them an emotional pathos and spatial flow that feels at once considered and dreamlike.

Often associated with negative space in Western art and design, which is known in Chinese as fu kongjian (负空间 fù kōngjiān), the subtle nuance in liubai goes beyond striking visual balance or helping to define the main subject of an image. The art of intentional blankness lies in the conscious creation of space for imagination, symbolism, and the spiritual. It allows something to be suggested and felt without giving it definitive form.

Liubai is widely applied across Chinese painting, ceramics, calligraphy, poetry, music, and theater, evoking mood, suggesting meaning, and leaving space for imagination and contemplation. Within a blank space, we can visualize drifting clouds, morning mist, distant mountains, and flowing rivers.

In this way, we are invited to explore the unknown, where beauty emerges not only in what is revealed but also in what is left undefined. In a space where meanings transcend form, we are invited to wander and dream.

Liubai shares an affinity with the concept of ma in Japanese art, written in Kanji as 間, which likewise focuses on the intention of negative space, not as absence, but as a presence equal in weight to the subjects it surrounds. The Japanese notion of yohaku no bi (余白の美), meaning the ‘beauty of empty space,’ was in fact shaped by liubai, introduced through Song-Yuan dynasty Chinese ink wash paintings brought back to Japan by Zen Buddhist monks in the 14th century. Zen-influenced Japanese painters were inspired by liubai in these paintings, and the concept gradually extended beyond painting into calligraphy, garden design, and flower arrangement.

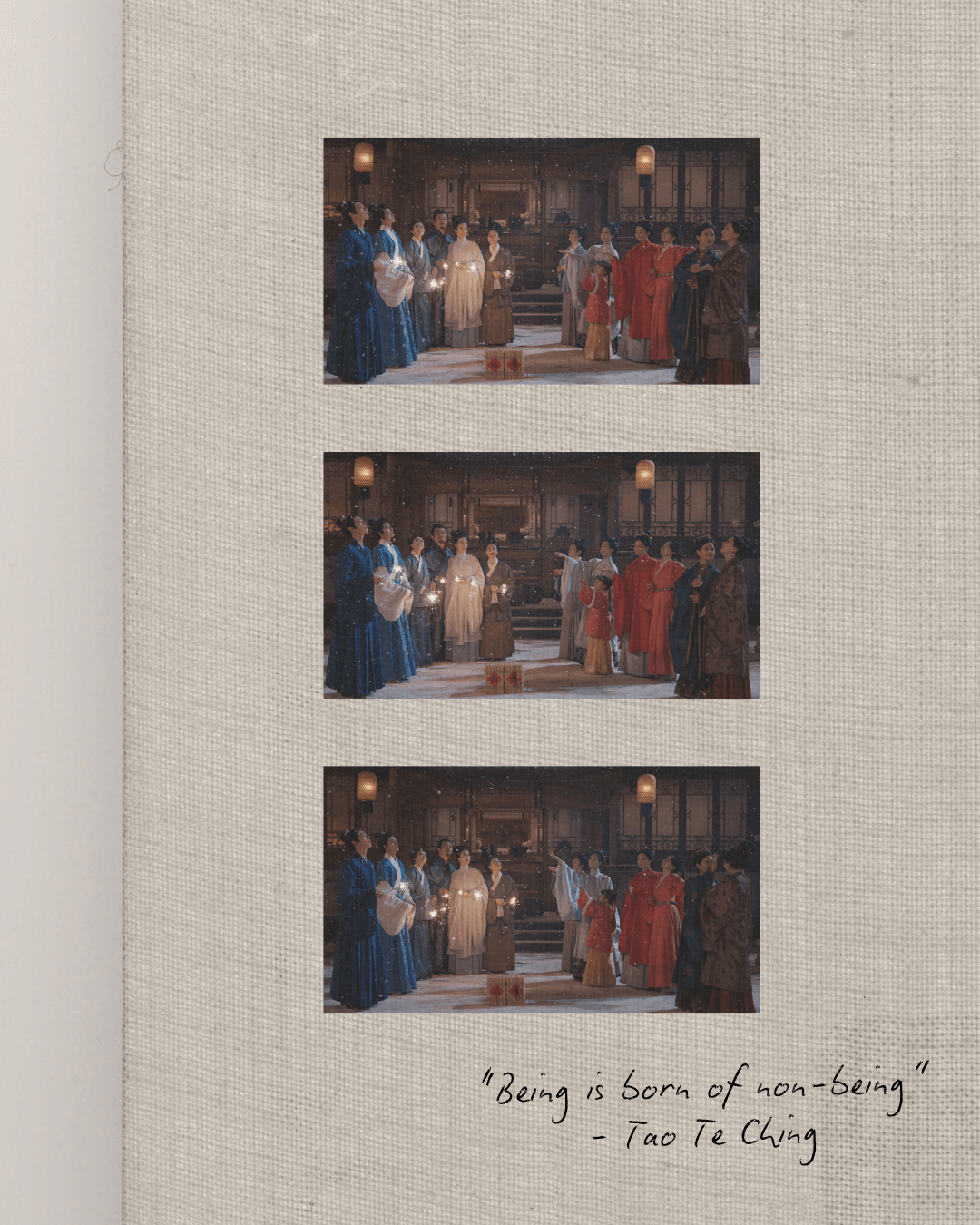

The philosophy behind liubai finds one of its earliest and most enduring expressions in the ’Tao Te Ching’ (《道德经》Dào Dé Jīng) by Chinese philosopher Laozi, also known as Lao Tzu. He writes that it is not the clay itself, but the empty space within that makes a vessel useful. Similarly, it is not the windows and doors, but the empty openings that let in air and light that make a house livable. With this observation, he concludes that “being brings benefit, while non-being makes things useful” (故有之以为利,无之以为用 gù yǒu zhī yǐ wéi lì, wú zhī yǐ wéi yòng).

The concept of ‘being’ (有 yǒu) and ‘non-being’ (无 wú) is explored further in the text, with Laozi writing: “all things under heaven are born of being; being is born of non-being” (天下万物生于有,有生于无 tiānxià wànwù shēng yú yǒu, yǒu shēng yú wú). Here, ‘being’ emerges from ‘non-being.’ Non-being is not lack or absence, but the fertile ground from which form, meaning, and life arise. All things follow this cycle, coming into being, and returning to non-being, and so on.

This insight from the ‘Tao Te Ching’ aligns with the concept of liubai and the open spaces the drama invites us to enter. Within these spaces, meanings and possibilities emerge — layered, nuanced, and open to interpretation.

Kuangjing: Framed Scenery

Kuangjing (框景 kuāngjǐng), meaning ‘framed scenery,’ is a core compositional technique in classical Chinese art, architecture, and garden design.

Doorways, windows, hanging eaves, columns, and tree branches serve as aesthetic borders, enclosing and highlighting views, architectural elements, and natural features within a defined space.

Kuangjing often works in tandem with jiejing (借景 jièjǐng), meaning ‘borrowed scenery.’ Even when the immediate surroundings are unremarkable, the techniques of borrowing and framing allow designers to incorporate visually interesting elements in the distance into a scene, including features such as mountains, rivers, bridges, and towers.

The drama draws inspiration from the framed scenery techniques of the Humble Administrator’s Garden, a Ming dynasty landmark, through its recurring use of moon gates as compositional frames that lend gravitas to key scenes.

These circular frames draw us in to pause, observe, and reflect, as characters move through the space, bringing new emotional and narrative layers into focus.

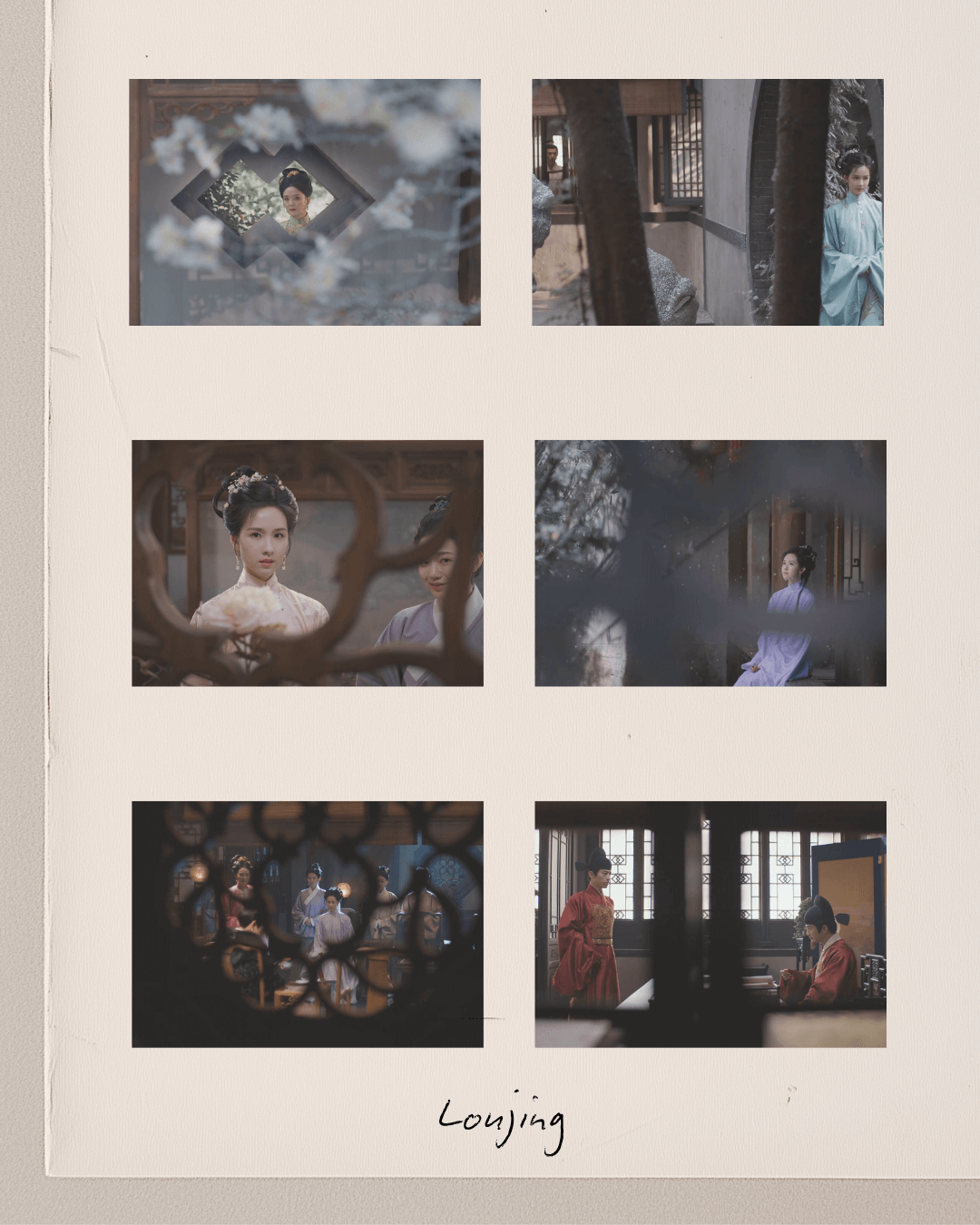

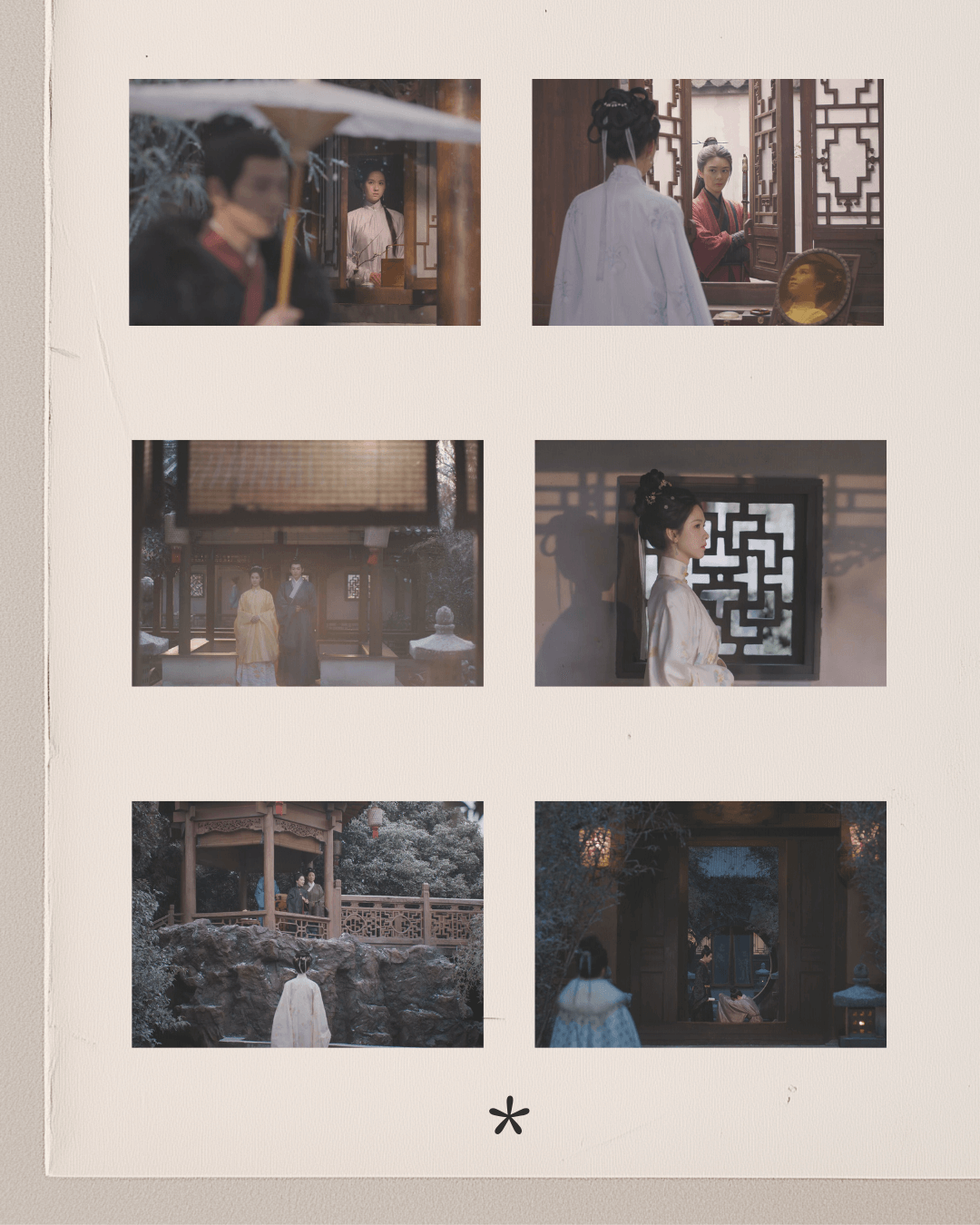

Loujing: Leaked Scenery

Loujiing (漏景 lòujǐng), meaning ‘leaked scenery,’ is a traditional compositional technique that evolved from the framed scenery of kuangjing. It offers a partial glimpse of a framed scene, rather than presenting it in its entirety.

This effect is achieved through the use of decorative openwork windows, semi-transparent screens, perforated walls, fences, and sparse arrangements of trees and plants. These elements allow viewers to peer beyond them, piquing curiosity and inviting closer observation. By allowing the line of sight to slip between spaces and cross thresholds, loujing creates a visual experience that is layered, nuanced, and intimate.

The drama often employs loujing to let viewers observe both the watcher and the watched, as a character quietly takes in a scene unfolding just beyond a wall or partition. It draws us into the emotional tension of the moment, as well as the reactions of those nearby, subtly revealing hidden motives and shifting power dynamics.

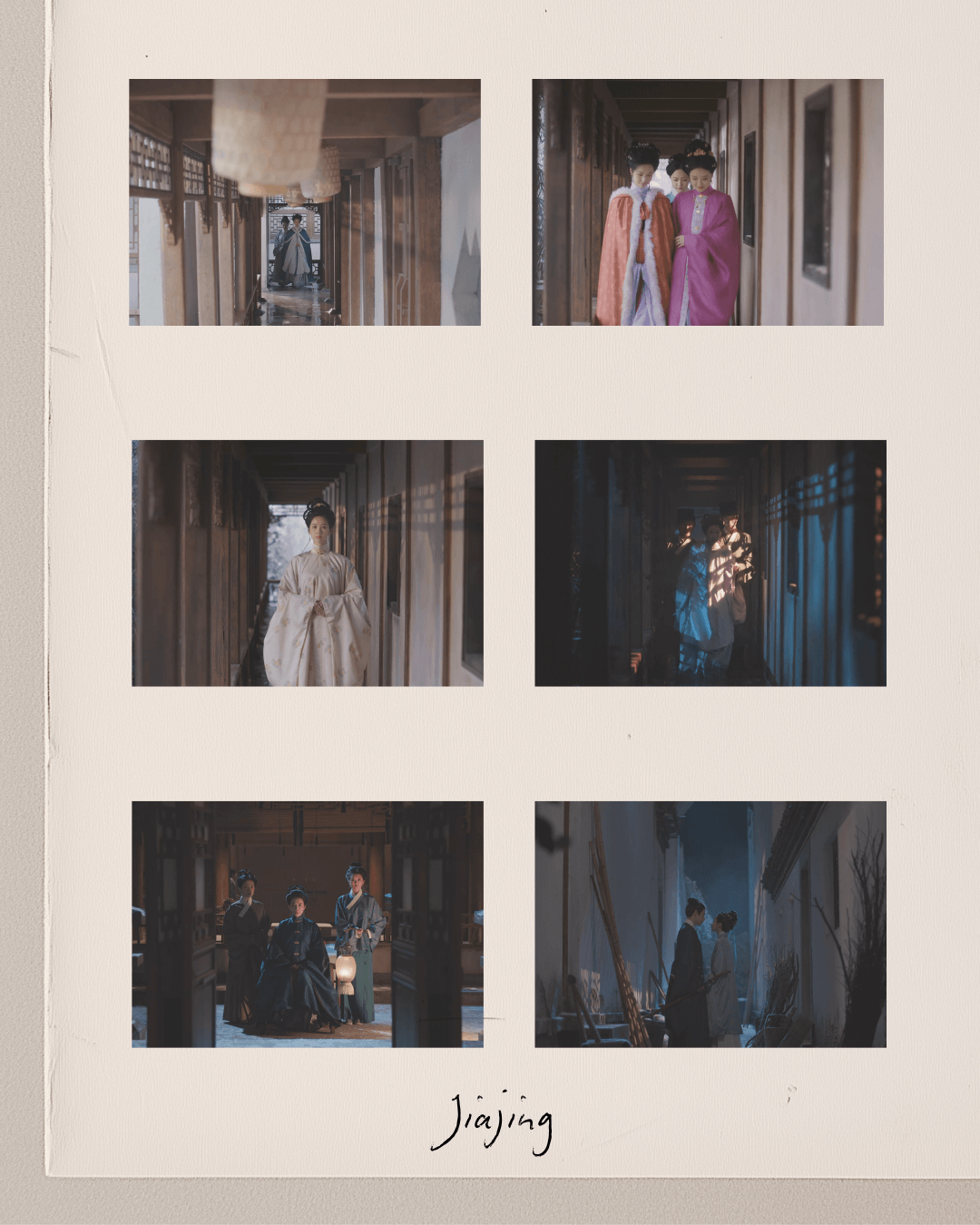

Jiajing: Flanked Scenery

Jiajing (夹景 jiājǐng), meaning ‘flanked scenery,’ is another traditional compositional technique from Chinese garden design that can be spotted in ‘The Glory’. Structures are placed on both sides of a view to form a visual corridor, guiding our gaze toward a focal point and amplifying its impact.

In garden design, this technique is often used to screen off less ideal surroundings and enhance spatial depth. Jiajing frequently appears along pathways and waterways, flanked on both sides by buildings, columns, fences, trees, or plants. This setup heightens the drama of the central view and draws the eye toward a subject in the distance, which could be a mountain, tower, bridge, or a figure walking toward the camera, as seen in the drama.

The drama uses jiajing both to direct the viewer’s gaze and intensify the mood of a scene. It emphasizes a character’s inner state when they are being led down a path, both physically and metaphorically, and feeling restless, trapped, uneasy, or determined. At the same time, jiajing draws focus to visually striking elements along the character’s path that add depth and momentum to the scene.

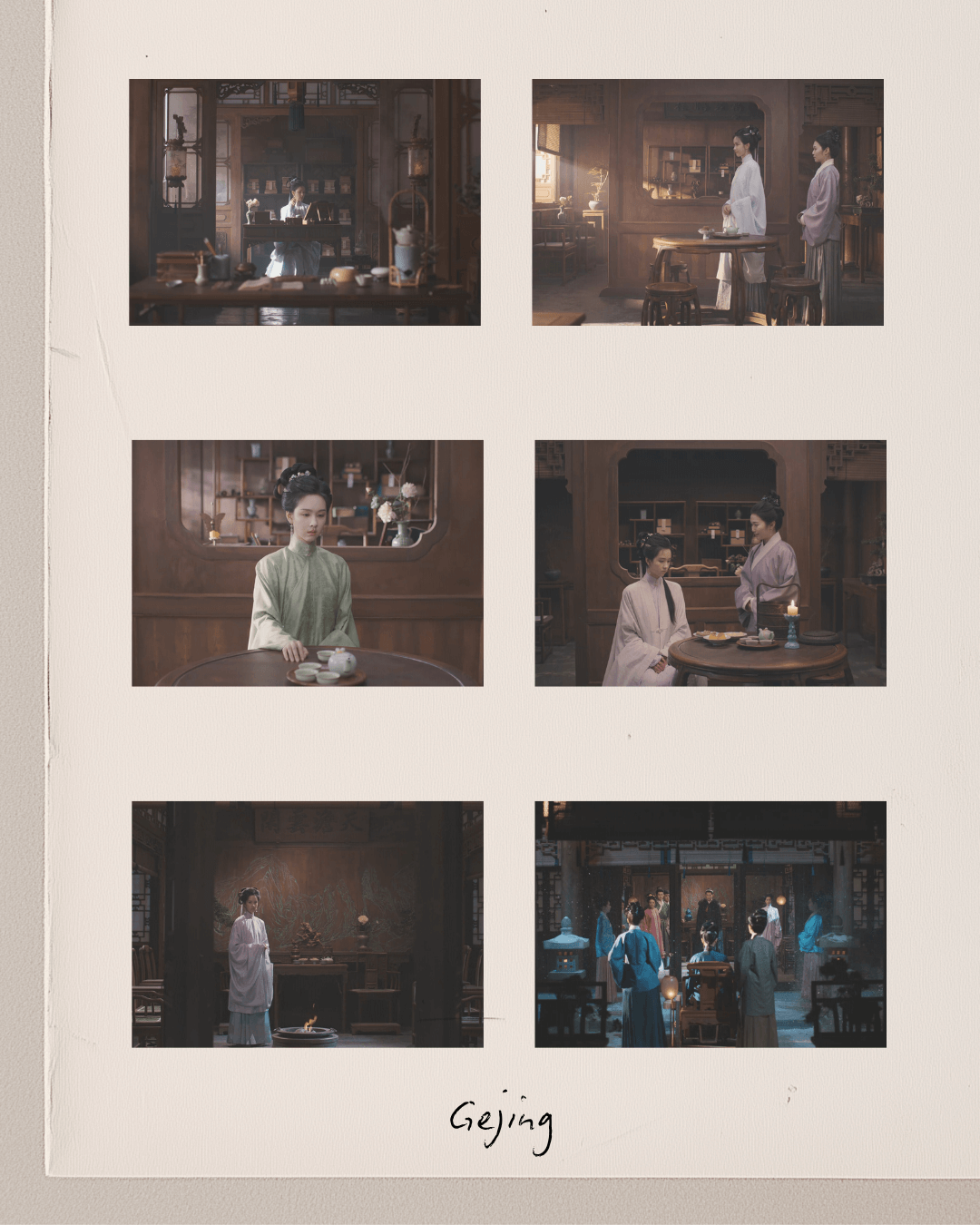

Gejing: Partitioned Scenery

Gejing (隔景 géjǐng), or ‘partitioned scenery,’ divides a garden or space into different zones, creating the experience of ‘a garden within a garden’ (园中有园 yuán zhōng yǒu yuán) and ‘a scene within a scene’ (景中有景 jǐng zhōng yǒu jǐng). It enriches spatial composition by allowing us to see the ‘large through the small’ (以小见大 yǐ xiǎo jiàn dà), as layers of scenery unfold before our eyes.

By partitioning space with screens, latticed windows, walls, doorways, walkways, fences, pavilions, bridges, rock formations, and trees, we introduce variation and reduce interference between different scenic zones, while preserving the continuity of the view. The result is layered depth and a dynamic visual experience that shifts as we move through the space — a hallmark of classical chinese garden design.

Many scenes in the drama use this technique to visually segment space with partitions, panels, and doorways, dividing the frame into distinct zones that reflect the characters’ emotional states and their shifting dynamics with one another as new information comes to light.

Gejing also separates ensemble scenes into visually distinct groupings, highlighting each character’s individual personality as well as their position within a group.

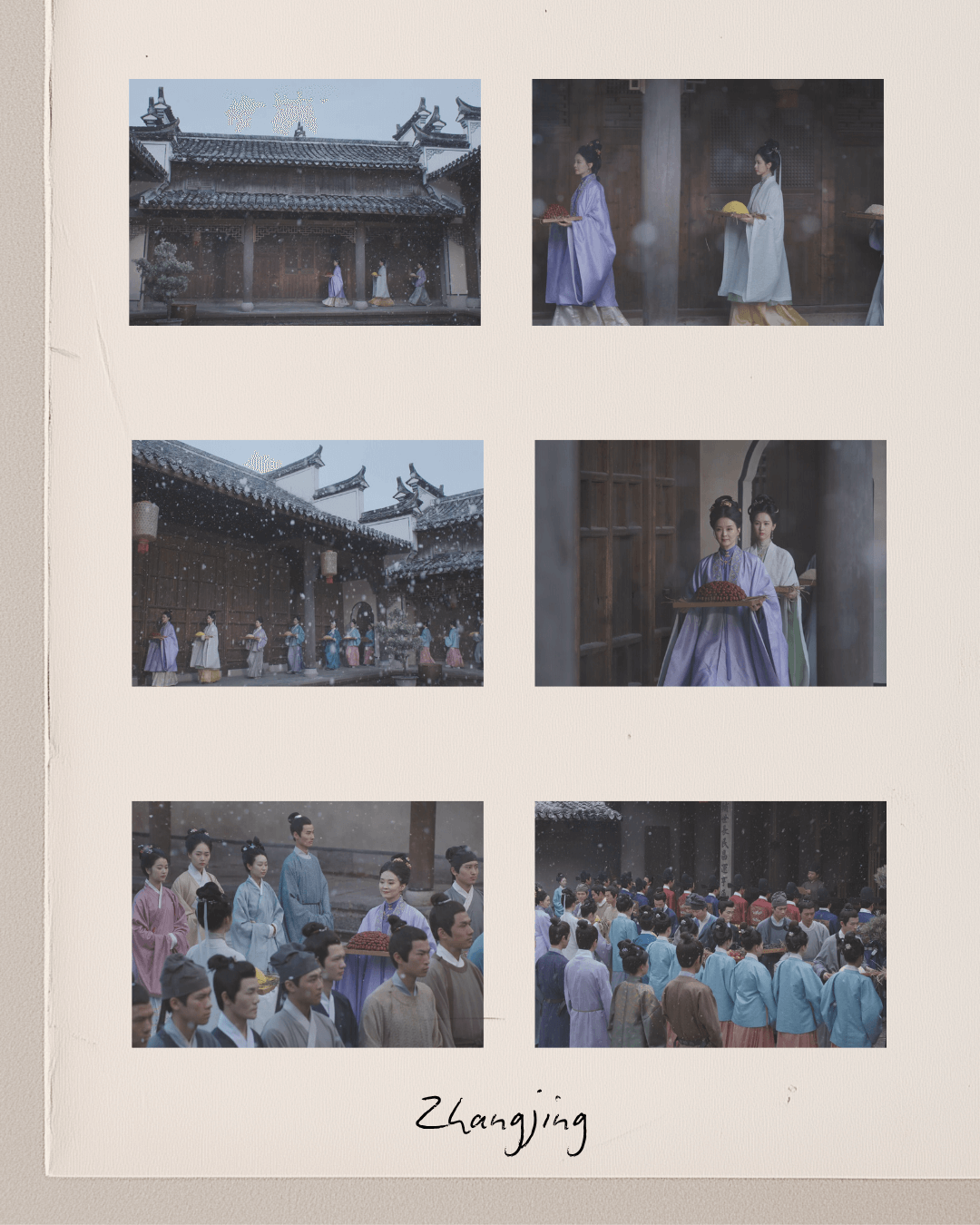

Zhangjing: Obstructed Scenery

Zhangjing (障景 zhàngjǐng), or ‘obstructed scenery,’ is a classical compositional technique that places visual barriers, such as screens, trees, rocks, and architectural features, at key points of transition to guide our movement and perception of a space, one step at a time.

With the Humble Administrator’s Garden in Suzhou serving as an important visual reference for the production design and cinematography of this drama, we can look more closely at the garden’s layout to understand how zhangjing works in practice. This classical garden deliberately dodges symmetry and axial alignment. Instead, its winding paths bend and twist through the landscape, encouraging us to meander, reflect, and discover new perspectives with each step.

Rather than revealing everything all at once, these curving paths follow the principle of ‘first conceal, then reveal’ (欲露先藏 yù lù xiān cáng) to heighten both visual and emotional impact. A single turn may suddenly open out onto a breathtaking vista, sparking surprise and wonder. In classical Chinese garden design, this technique redirects attention, obscures less desirable views, and creates an immersive experience of space.

Together with loujing (漏景 lòujǐng), or ‘leaked scenery’, the art of zhangjing embodies the Chinese aesthetic ideal of ‘finding beauty in the hidden and the secluded’ (以隐幽为美 yǐ yǐn yōu wéi měi). Fittingly, the plaque above the Zhuang residence reads Ju You (居幽 jū yōu), meaning ‘to dwell in seclusion.’

To see the whole picture, we are invited to slow down, look closely, and experience the world around us from multiple vantage points. Like the garden it draws from, the world of the drama encourages mindful observation as our lead characters move through layers of deception and revelation, digging deeper into the truth.

The Philosophy of Chinese Aesthetics

Classical Chinese aesthetics are rooted in a cultural worldview shaped by centuries of refinement and philosophical thought, drawing on the influences of Daoism, Zen Buddhism, and Confucianism.

This aesthetic tradition leans toward subtlety and ambiguity, embracing the void, stillness, and emotional depth.

Within this worldview, beauty is meant to be appreciated gradually over time and through reflection, rather than consumed in a single glance. We are invited to engage with art at a leisurely pace, guided by our imagination, and move beyond the physical landscape into realms of emotion, symbolism, and transcendence.