Upon the founding of the Ming dynasty, the Hongwu Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang sought to restore continuity with earlier Han Chinese dynasties through a standardized clothing system. That’s why Ming dynasty clothing is often described as “inheriting from the Zhou and Han, drawing from the Tang and Song” (上采周汉,下取唐宋 shàng cǎi zhōu hàn, xià qǔ táng sòng).

Specific colors, motifs, and accessories were assigned to different ranks and classes to signify hierarchy, clearly distinguishing the emperor, royalty, nobility, and officials from one another and from commoners, though these regulations gradually loosened by the late Ming. Overall, Ming-style clothing is renowned for its modest elegance and coordinated layering.

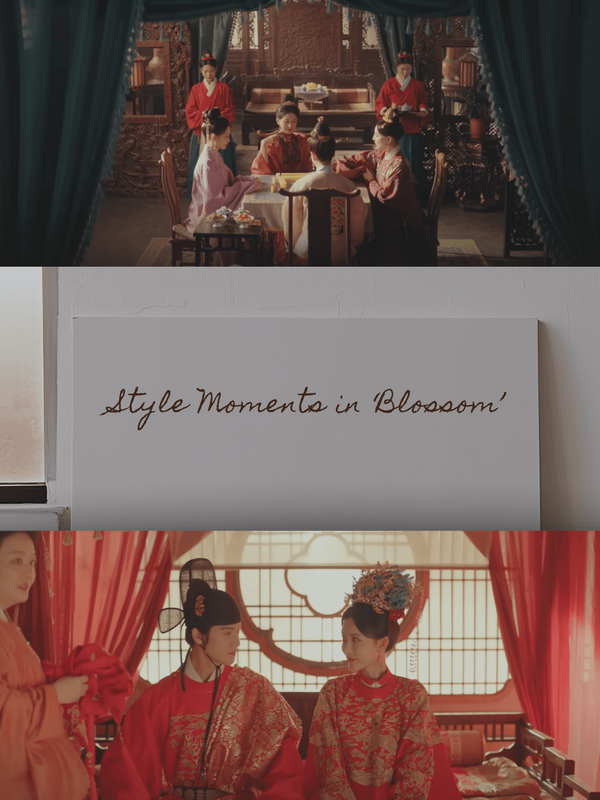

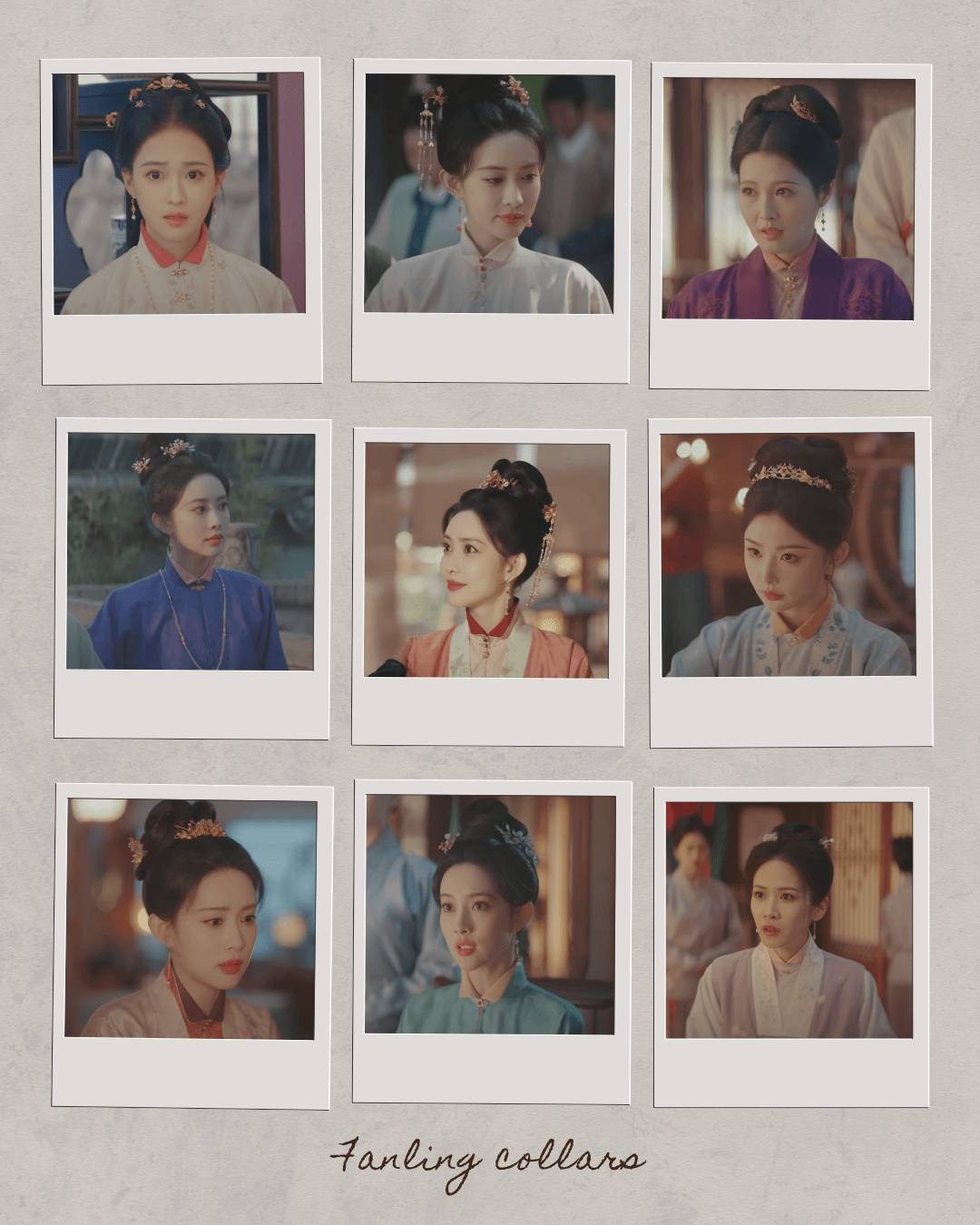

Blossom, starring Meng Ziyi and Li Yunrui, adapts key stylistic features from the Ming dynasty with thoughtful attention to detail, especially where they enrich the narrative and enhance character development.

Here are the most interesting Ming-style clothing details woven into the drama’s costume design.

Collars

Most collars for both men and women featured a jiaoling youren (交领右衽 jiāolǐng yòurèn) design, which is a crossed collar (jiaoling) with a right-wrapped panel (youren) that crosses from left to right to form a Y-shaped neckline.

In addition, other collar styles included the round collar, known as yuanling (圆领 yuánlǐng), straight or parallel collar, known as zhiling (直领 zhílǐng), and the square collar, known as fangling (方领 fānglǐng).

By the late Ming dynasty, standing collars, known as either liling (立领 lìlǐng) or shuling (竖领 shùlǐng), had become a distinctive feature of women’s clothing. Structurally, the standing collar evolved from the protective collar of inner garments.

Theories behind the popularity of this collar style include:

1. The colder climate of the ‘Little Ice Age’

A notably colder period spanned from the 1570s, during the Wanli era, to the 1730s, extending beyond the fall of the Ming dynasty.

2. A shift toward increasingly demure clothing

Higher necklines reflected the era’s emphasis on modesty and restraint.

3. A desire to showcase metal clasp buttons

Standing collars provided a visible place to display ornate fastenings as status symbols.

Fanling: Turned-Down Collars

This is where a striking Ming dynasty costume detail in the drama shines with great execution. Made from pliable fabric, these standing collars allowed the corners to be folded down, creating a turned-down collar known as the fanling (翻领 fānlǐng).

Instead of folding down the entire collar or attaching a separate piece to mimic the effect, the drama stays true to what is seen on historical paintings and artifacts by turning down only the corners, revealing the lining on the reverse side, often in a contrasting color.

Zimu Kou: Metal Clasp Buttons

Metal clasp buttons, known as zimu kou (子母扣, zǐmǔ kòu), are traditional clothing fasteners that were developed during the Ming dynasty, aided by advancements in metalworking technology. These fasteners are recognized as one of the era’s most distinctive ornamental details. True to their name, they feature a distinctive ‘mother-and-child’ interlocking design.

Intricately crafted from precious metals, sometimes jade, or a combination of metal and gemstones, zimu kou served not only as practical fasteners but also as luxurious status symbols, much like fine jewelry.

Often showcased on standing collars and turned-down collars, these clasp buttons added an elegant finishing touch and helped secure the collar more snugly around the neck, fulfilling both functional and decorative roles.

Zhuiling: Collar Pendants

The zhuiling (坠领 zhuìlǐng) is a distinctive hanging ornament worn at the collar or neckline, traditionally serving as a focal point for decorative elements. It is often embellished with buttons, intricate embroidery, or various types of necklaces and accessories. Zhuiling ornaments enhance the overall elegance of a woman’s attire.

Gu Qiyuan’s seventeenth-century commentary on consumerism in China, titled ‘Superfluous Remarks Made at the Parlor’ (《客座赘语》 kèzuò zhuìyǔ), discusses accessories and their names based on where they were worn:

Various ornaments, crafted from gold, pearls, and jade, are intricately shaped, featuring motifs such as mountain and cloud patterns or floral designs. Long cords are threaded through these decorative pieces, allowing them to be suspended and worn in different ways. Some are draped across the chest and are known as zhuiling.

In addition, according to the ‘Collected Statutes of the Ming dynasty’ (《大明会典》 Dà Míng Huìdiǎn), zhuiling were less strictly regulated and could be worn by women across all social classes. Women from wealthy families often wore zhuiling made from precious materials such as gold, jade, pearls, and emeralds.

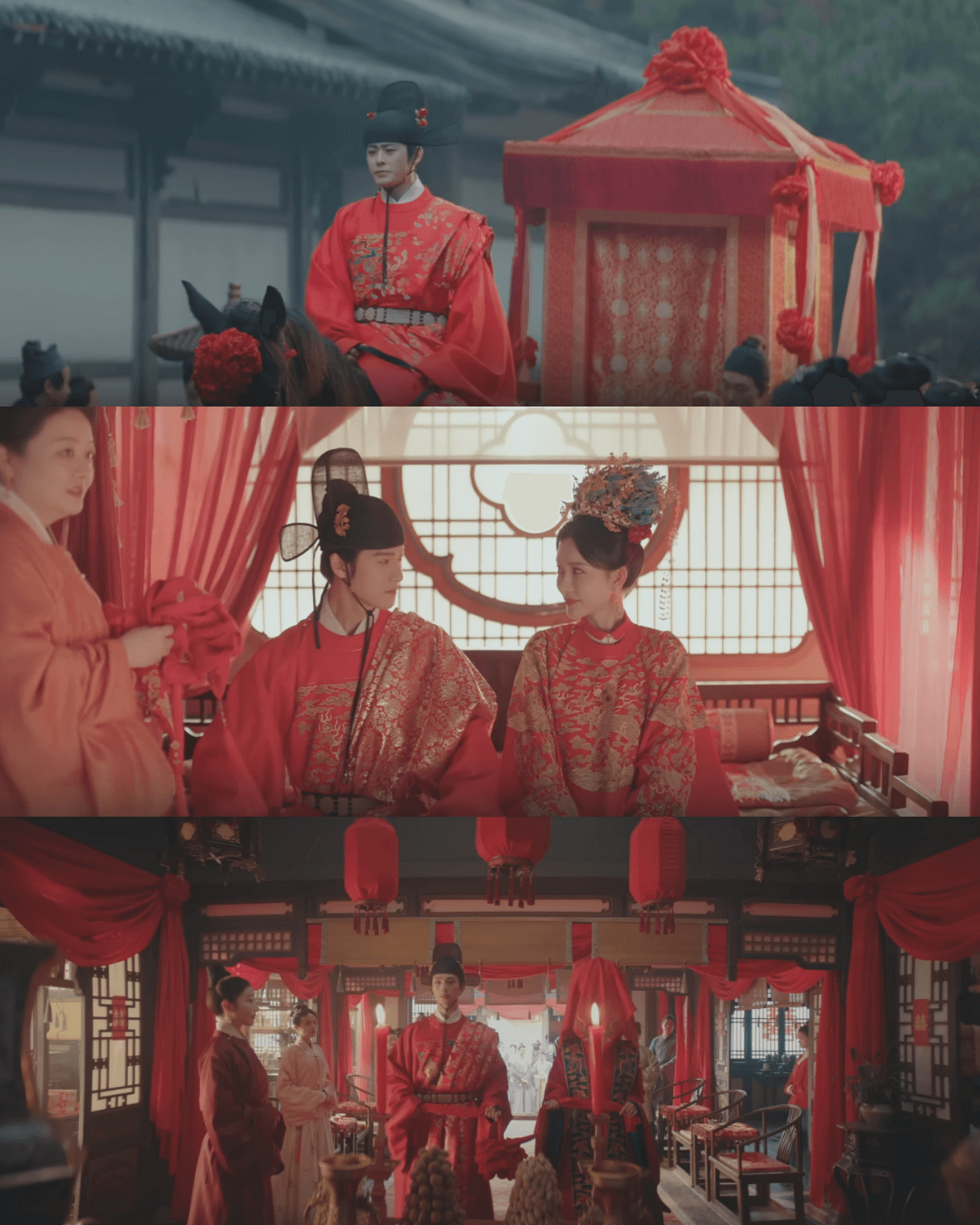

Ceremonial Attire

Pihong: Ceremonial Red Sashes

These stunning examples of pihong (披红 pīhóng) featured in the drama are a type of ceremonial sash traditionally worn at weddings and official ceremonies during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

The pihong was originally bestowed upon the top scholar who achieved the highest rank in the imperial examination, along with floral hairpins worn on headwear known as zanhua (簪花 zānhuā), as a mark of honor from the royal court in a tradition known as ‘top scholar worship’ (状元崇拜 zhuàngyuán chóngbài).

The Ming dynasty opera ‘The Top Scholar’s Triumphant Return' (《状元荣归》Zhuàngyuán Róngguī) depicts the celebratory homecoming of a newly appointed top scholar, wearing a Tang-style headscarf (唐巾 táng jīn) adorned with zanhua and draped in a pihong.

Over time, scholars who achieved the ranks of juren (举人 jǔrén) and jinshi (进士 jìnshì) were also granted this honor.

Eventually, the pihong became an integral part of traditional weddings, which was likened to a ‘minor imperial examination’ (小登科 xiǎo dēngkē) for the groom by the late Ming. As a folk saying goes, “a wedding is just like passing a minor imperial examination. Draped in a red sash and adorned with a floral hairpin, the groom resembles a top scholar.” (新婚胜如小登科,披红簪花煞似状元郎。xīnhūn shèng rú xiǎo dēngkē, pīhóng zānhuā shā sì zhuàngyuán láng.)

‘Marriage Destinies to Awaken the World' (《醒世姻缘传》 xǐngshì yīnyuán zhuàn), a classic novel from the late Ming or early Qing dynasty, contains multiple references to the pihong, such as “Di Xichen rode on horseback in full formal attire with pihong and zanhua,” which is exactly what Song Mo (Li Yunrui) does at the beginning of his wedding scene.

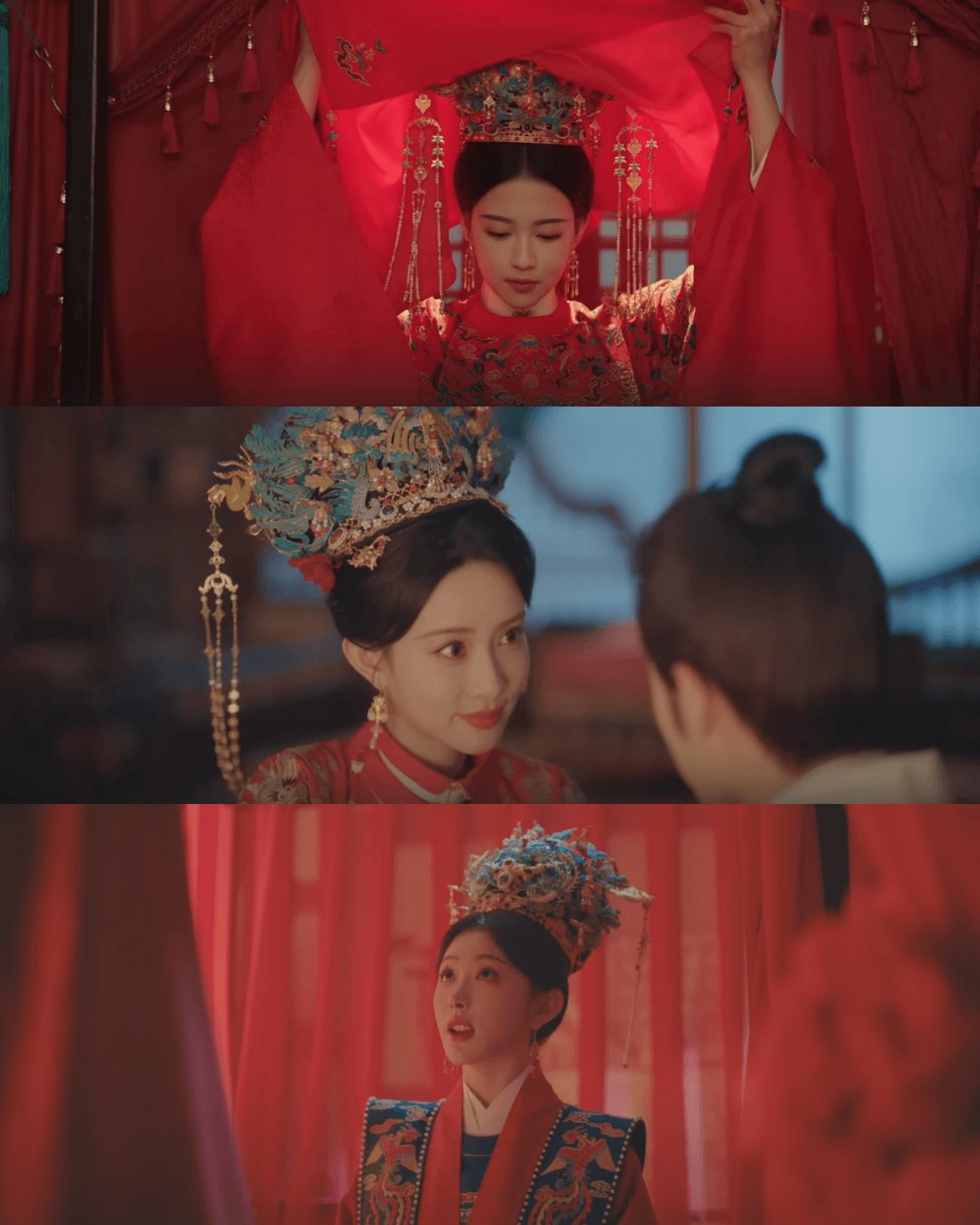

Fengguan: Phoenix Crowns

The fengguan (凤冠 fèngguān) is a type of traditional ceremonial headwear worn by women. In the Ming dynasty, the empress, imperial consorts, princesses, and titled noblewomen, such as the wives of officials, wore variations of this headwear, broadly categorized under the fengguan umbrella, with embellishments that reflected their rank.

The Ming dynasty’s fengguan was built on structural foundations established in the Song dynasty. It featured a cap-like base reinforced with a gold wire framework, covered with gauze, and adorned with inlaid gold, silver, pearls, and gemstones. Over time, designs became more elaborate, incorporating new elements such as ornate side flaps called bobin (博鬢 bóbìn), decorative frames, and beaded tassels.

During the Ming dynasty, ordinary women were allowed to wear a fengguan at their wedding ceremony, due to a longstanding special privilege known as she sheng (攝盛 shè shèng), which permitted individuals to wear attire and ride in carriages belonging to a higher rank for special occasions.

In ‘Collected Manuscripts from the Year of Guisi: Reflections on Wedding Rituals and Attire’ (《癸巳存稿·昏礼摄视议》Guǐsì Cúngǎo · Hūnlǐ Shèshì Yì), Qing dynasty scholar Yu Zhengxie cites the ‘History of Ming: Treatise on Attire and Carriages’ (《明史·舆服志》Míngshǐ · Yúfú Zhì) to explain that “in commoner marriages, they were permitted to borrow ninth-rank official robes,” a practice he identifies as “an example of she sheng.”

There’s a folk legend about how all women came to wear the fengguan on their wedding day, dating back to the Song dynasty, when the future emperor Zhao Gou was rescued by a young village woman. Years later, when he ascended the throne as Emperor Gaozong, he sought to repay her kindness and sent envoys to escort her to the palace, but she declined the offer and did not enter the court.

To express his gratitude, Emperor Gaozong issued a decree granting the maiden the honor of an empress’s wedding ceremony, allowing her to wear a phoenix crown ensemble and ride in a ceremonial palanquin, privileges that had previously been exclusive to the imperial family.

Over time, as more women adopted this custom, fengguan became an iconic part of chinese bridal attire, giving rise to the distinctive fengguan xiapei (凤冠霞帔 fèngguān xiápèi) wedding ensemble, which is what Miao Ansu (Kong Xue’er) wears to her wedding. The xiapei in the Ming dynasty resembles a long ceremonial band worn around the neck.

It’s worth expanding on how fengguan serves as an umbrella term for this type of ceremonial headwear. Under the official clothing system, the number and types of ornaments on a woman’s fengguan were strictly determined by rank. As a result, the crowns worn by noblewomen and commoners often lacked the phoenix (凤 fèng) motifs that defined a true fengguan, and were alternatively referred to as diguan (翟冠 dígūan), meaning ‘pheasant crowns.’ While titled noblewomen and regular women from wealthier families might afford more elaborate versions adorned with pheasant ornaments, pearls, gold, emeralds, and precious gemstones, most commoners could afford simpler crowns, sometimes referred to as huaguan (花冠 huāguān), meaning ‘floral crowns.’

There is another exception to the privilege of wearing fengguan at weddings. Women who were remarrying or being married into a household as a concubine were not permitted to wear fengguan. In ‘Blossom,’ Wang Yingxue (Zhang Meng) laments to her daughter Dou Ming (Li Baihui), “your mother never had the chance to wear this in her lifetime. I hope that when you wear it tomorrow, it will bring you a smooth life in return.”

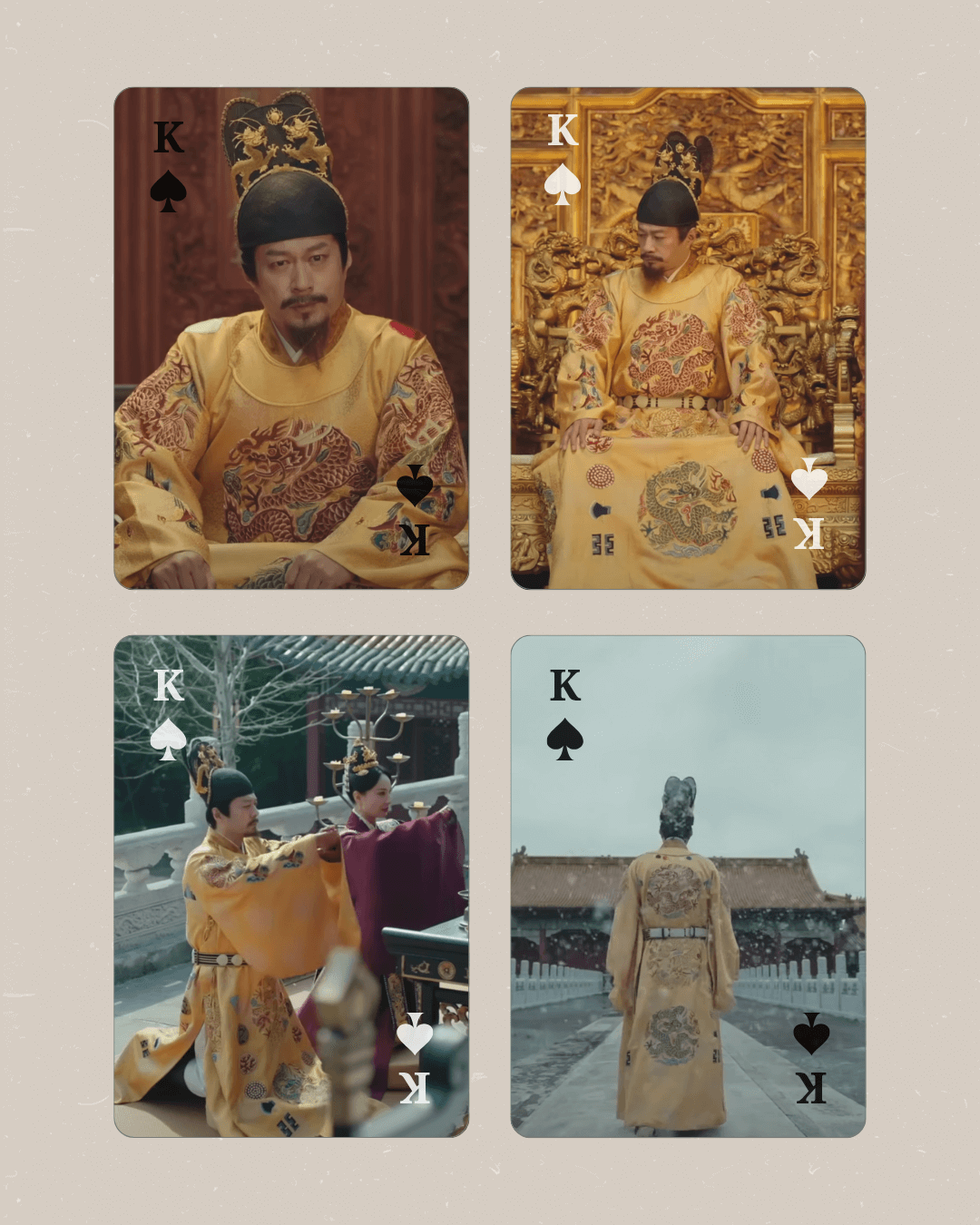

Shi’Er Zhang: Twelve Ornaments

The Emperor (Tan Kai) in ‘Blossom’ wears a yellow dragon robe emblazoned with twelve ornaments. These twelve ornaments, known as shi’er zhang (十二章 shí’èr zhāng), are ancient symbols used exclusively as insignia by emperors of imperial China. They symbolized the virtues of an ideal ruler, reinforcing the emperor’s authority as heaven’s appointed ruler and legitimizing their divine mandate to govern.

Their origins can be traced back to the legendary reign of Emperor Shun, who referred to them as “emblematic images of the ancients,” as recorded in the ‘Book of Documents’ (《尚书 》 shàng shū).

While interpretations of each symbol vary across different scholarly writings, including commentaries on texts such as the ‘Rites of Zhou’ (周礼 zhōu lǐ), their common visual representation and meaning, as seen on Ming dynasty robes, are as follows:

- Sun (red circle), moon (white circle), and stars (colored dots representing the five cardinal directions) for clarity and enlightenment.

- Mountains for stability, steadfastness, and reverence.

- Dragons for transformation and adaptability.

- Huachong (华虫 huáchóng), a mythical bird typically depicted as a pheasant, for literary refinement.

- Zongyi (宗彝 zōngyí), sacrificial vessels for reverence, filial piety, and ancestral offerings.

- Algae for purity and cleanliness.

- Fire for brilliance, enlightenment, and integrity.

- Rice grains for nourishment and abundance in a prosperous nation.

- Axe for decisiveness and resolute leadership.

- Fu (黻 fú), a symbol for discernment between right and wrong, rejecting evil and embracing virtue.

Only the emperor could wear ceremonial robes adorned with the full set of these twelve ornaments. According to the ‘Records of Ming History: Administrative and Clothing Rites II’ (《明史·舆服二》 Míng Shǐ · Yú Fú Èr), the emperor’s ceremonial attire (袞冕 gǔnmiǎn) featured six ornaments each on the upper and lower robes: the sun, moon, stars, mountains, dragons, and huachong on the upper robe, and the zongyi, algae, fire, rice grains, axe, and fu symbols on the lower robe.

For an exploration of more fascinating motifs from the Ming dynasty, take a look at how they have been brought to life in the Chinese drama ‘The Glory’ here.

Outerwear

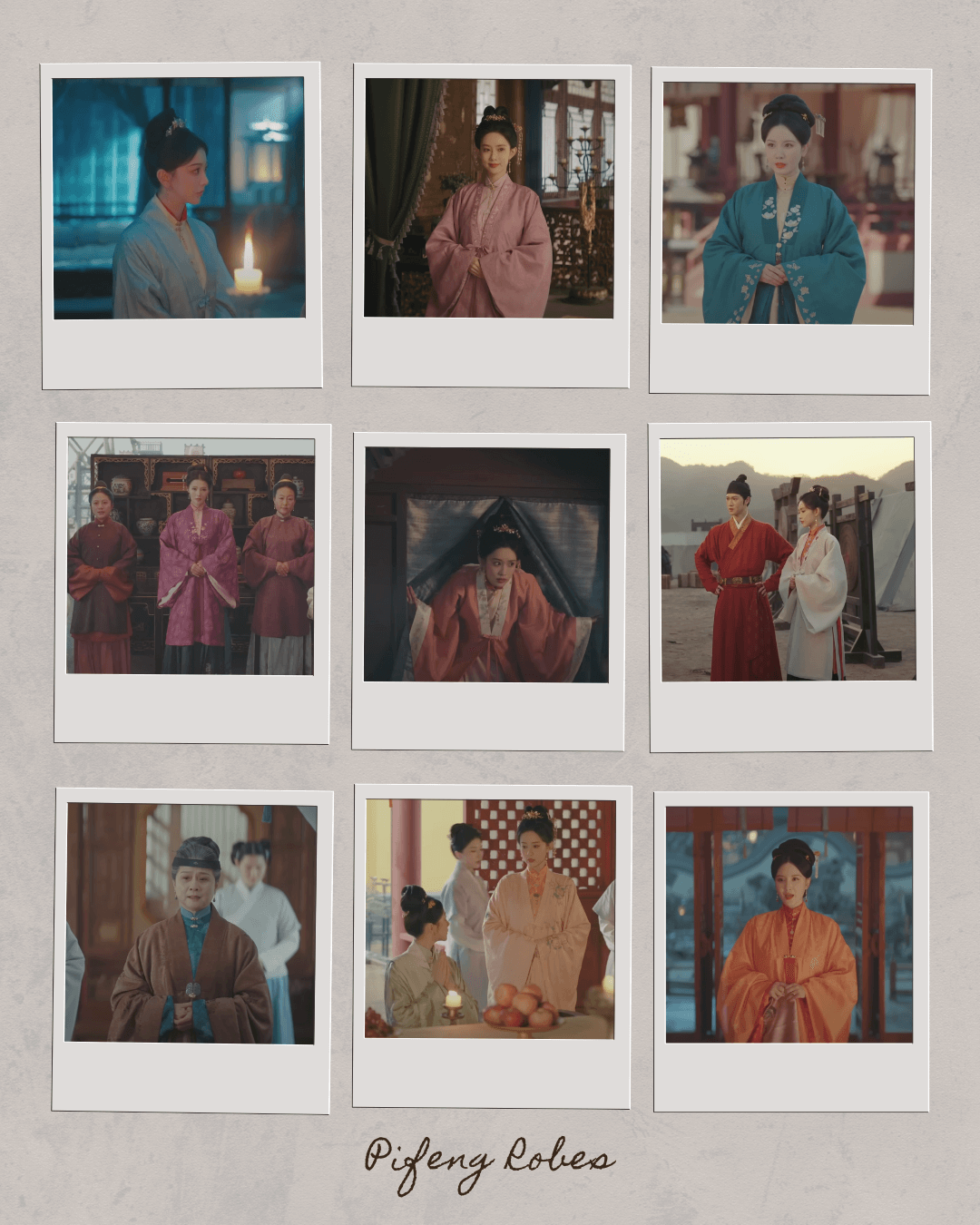

Pifeng: Outer Garments

The pifeng (披风 pīfēng) is, as its name suggests, a long outer garment designed for protection against the wind. It typically features a straight collar, known as zhiling (直领 zhílǐng), with parallel panels, duijin (对襟 duìjīn), in a wide, front-opening design. The garment fastens at the front with a metal clasp button or fabric ties, allowing the collar of the clothing underneath, with its ornate buttons, to remain prominently visible.

This outer garment has large, open sleeves and side slits for enhanced ease of movement, along with separate front and back panels, distinguishing it from a cloak known as the doupeng (斗篷 dǒupeng), with which it is sometimes conflated.

Ming dynasty portraits and historical texts show that the pifeng was a popular and versatile garment, worn both indoors and outdoors. The late-Ming text ‘Recorded Observations from Yunjian’ (《云间据目抄》 yúnjiān jù mù chāo) describes the pifeng as bianfu (便服 biànfú), meaning ‘everyday clothing.’

Notably, the pifeng is referenced multiple times in character descriptions throughout the classic novel Dream of the Red Chamber (《红楼梦》 hóng lóu mèng), which served as an important source of inspiration for ‘Blossom.’

The pifeng of the Ming and Qing dynasties is believed to have evolved from the beizi (褙子 bèizi) of the Song dynasty, a loose outer garment with wide, long sleeves. Ming dynasty scholar Wang Qi wrote in the encyclopedic text ‘Collected Illustrations of the Three Realms’ (《三才图会》sāncái túhuì) that “the beizi is what we now call the pifeng.”

Headwear

Diji: Sculpted Bun-Covering Headpieces

The diji (䯼髻 díjì) is a structured covering worn over hair buns by married women in the Ming dynasty, who styled their hair in updos. This versatile headpiece served as a base for securing hairpins and ornaments, which could be inserted into the framework to suit different occasions.

In the drama, noblewomen wear diji as part of both formal and everyday attire, whether at home or when visiting friends and relatives.

The diji was influenced by guan (冠 guān), as well as wig bun hairpieces known as jiaji (假髻 jiǎjì), meaning ‘fake buns,’ and baoji (抱髻 bàojì), meaning ‘covered bun’ or ‘wrapped bun’, which appeared in last year’s hit revenge drama The Double starring Wu Jinyan and Wang Xingyue.

With advancements in metalwork, Ming dynasty headwear became more elaborate than in previous eras, giving rise to the diji, which developed into a solid hat-like shell worn over a hair bun. Ming dynasty diji were typically crafted from gold or silver wire, onto which horsehair or human hair was woven, and covered with black gauze, giving it a conical shape.

The supportive framework of the diji allowed hairpins to become increasingly elaborate. Wearers could insert long, delicate hairpins through the metal framework at different angles. The central hairpin served as both a striking focal point and a practical anchor to keep hair securely in place.

Once the central hairpin was secured, additional hairpins were arranged around the bun. These accessories formed a headdress set collectively known as toumian (头面 tóumiàn), each piece named according to its placement and function within the hairstyle.

Beyond their aesthetic appeal, the diji represented refined artistic tastes, and by the mid-to-late Ming dynasty, artisans began incorporating embellishments directly onto the diji.

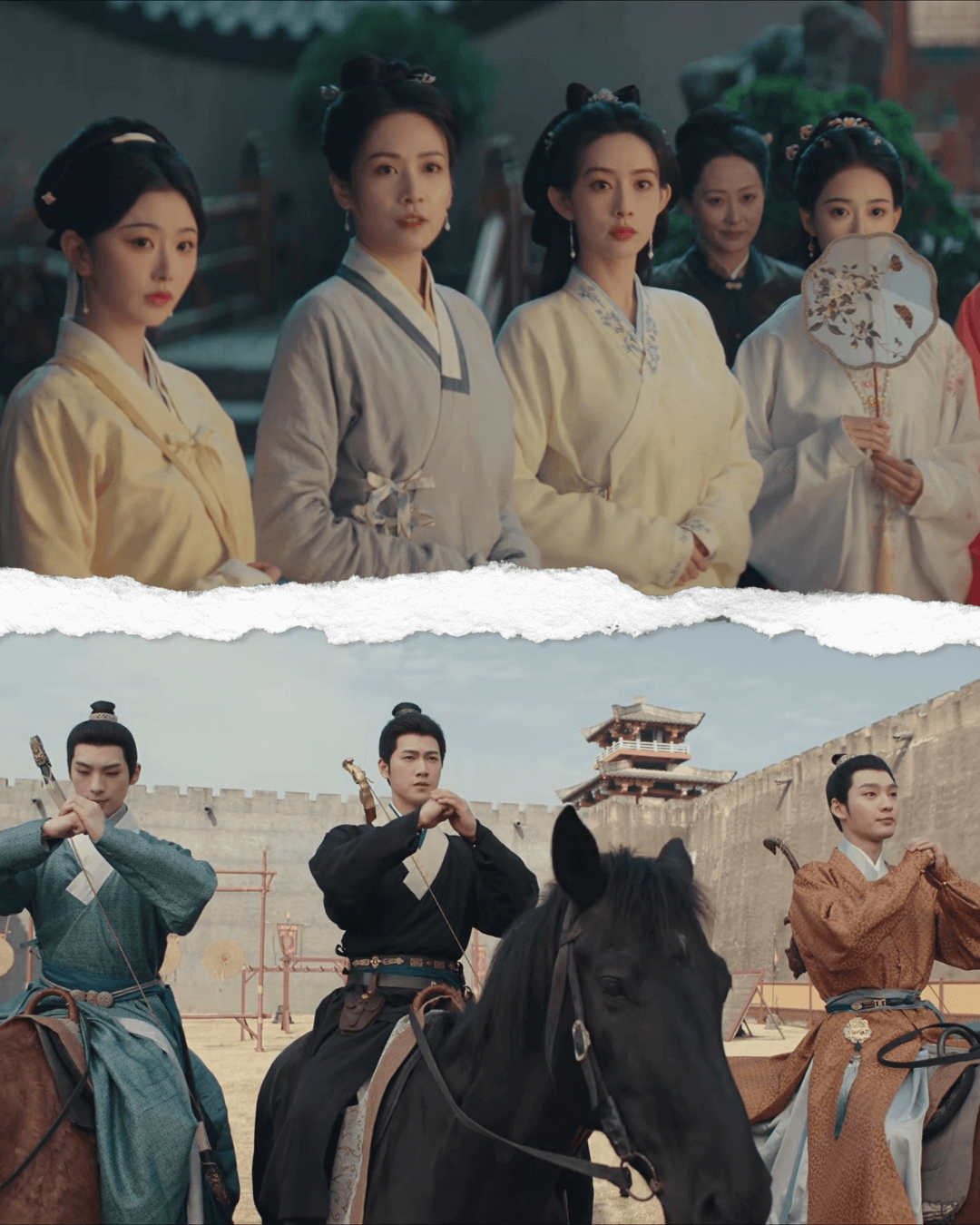

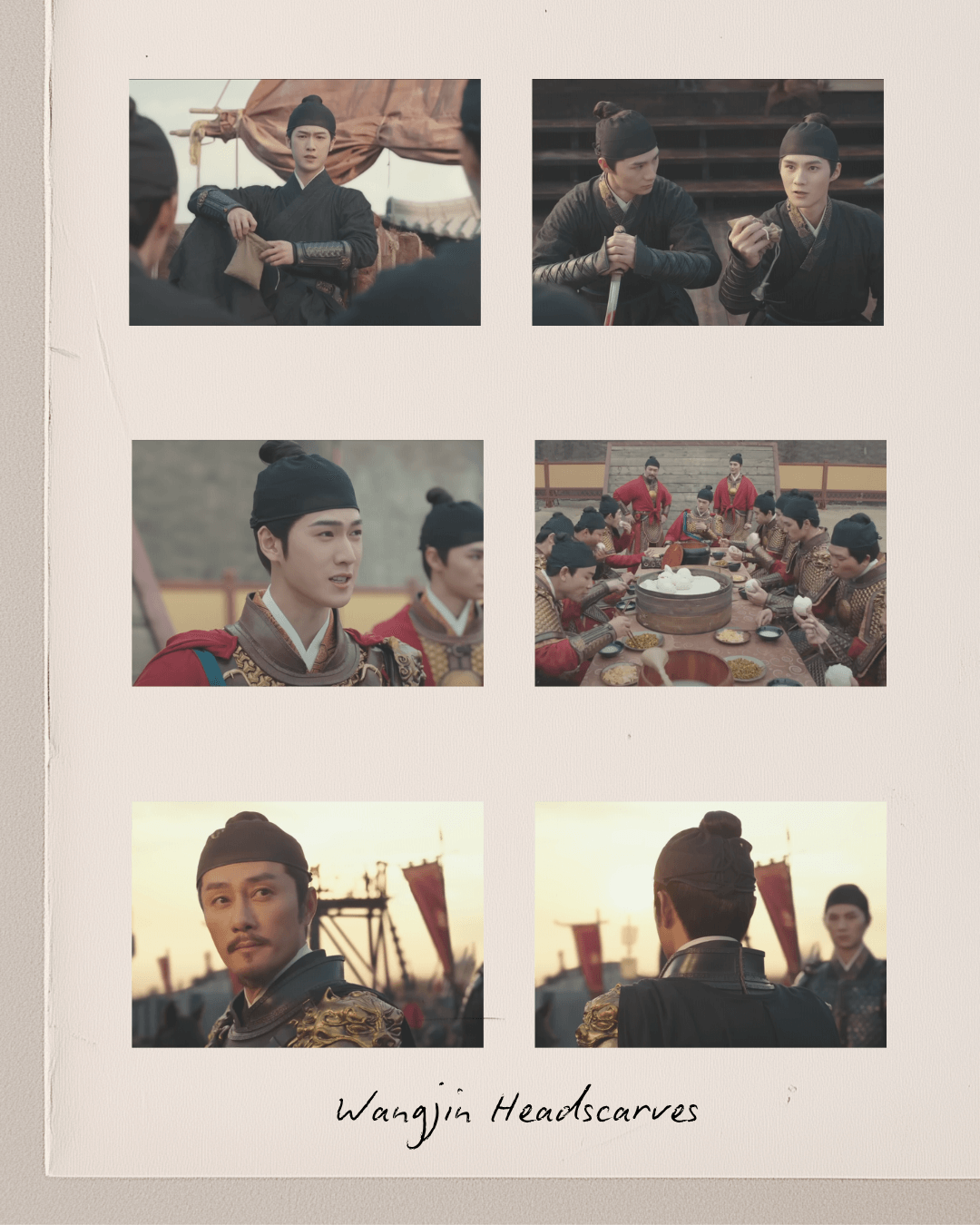

Wangjin: Netted Headscarves

The wangjin (网巾 wǎngjīn) is a type of hairnet worn by men in the Ming dynasty to secure their hair, and one of the most iconic headwear items established in the dynasty’s official clothing system.

Worn across all social classes, the wangjin was one of the least hierarchical accessories of the Ming era. It was also incorporated into the coming-of-age capping ceremony for young men, known as guan li (冠礼 guān lǐ), and even imperial princes were required to wear it.

In the early Ming period, the Hongwu Emperor issued an imperial decree mandating that all men wear the wangjin. Before that, the wangjin was part of Daoist attire and not widely popular. Legend has it that one day, the emperor learned from a monk that the purpose of the wangjin is to “gather all hair neatly together” (万发皆齐 wàn fā jiē qí). He found this concept to be the perfect symbol for stability and order. If all men across the land wore the wangjin, they would be unified and bound within the great net of his dynasty.

Structurally, the wangjin resembles a fishing net, with a broader bottom and a narrower top. The bottom edge features a band with two symmetrical loops, through which cords are threaded and tied to adjust the fit. The top has drawstring cords to secure it around the hair bun, keeping the wearer’s hair neat. To wear the wangjin, the net opening is expanded over the head, gathering all hair inside before tightening the silk cord to hold it in place. Initially woven from black silk, horsehair, or palm fiber, wangjin evolved during the Ming Dynasty’s Wanli era to incorporate both human hair and horse mane.

Noblemen and officials were required to wear an additional cap over the wangjin in public, while commoners often wore it on its own without extra headwear.

Wangjin Market in Nanjing takes its name from its origins as a marketplace specializing in the sale of wangjin during the Ming dynasty.

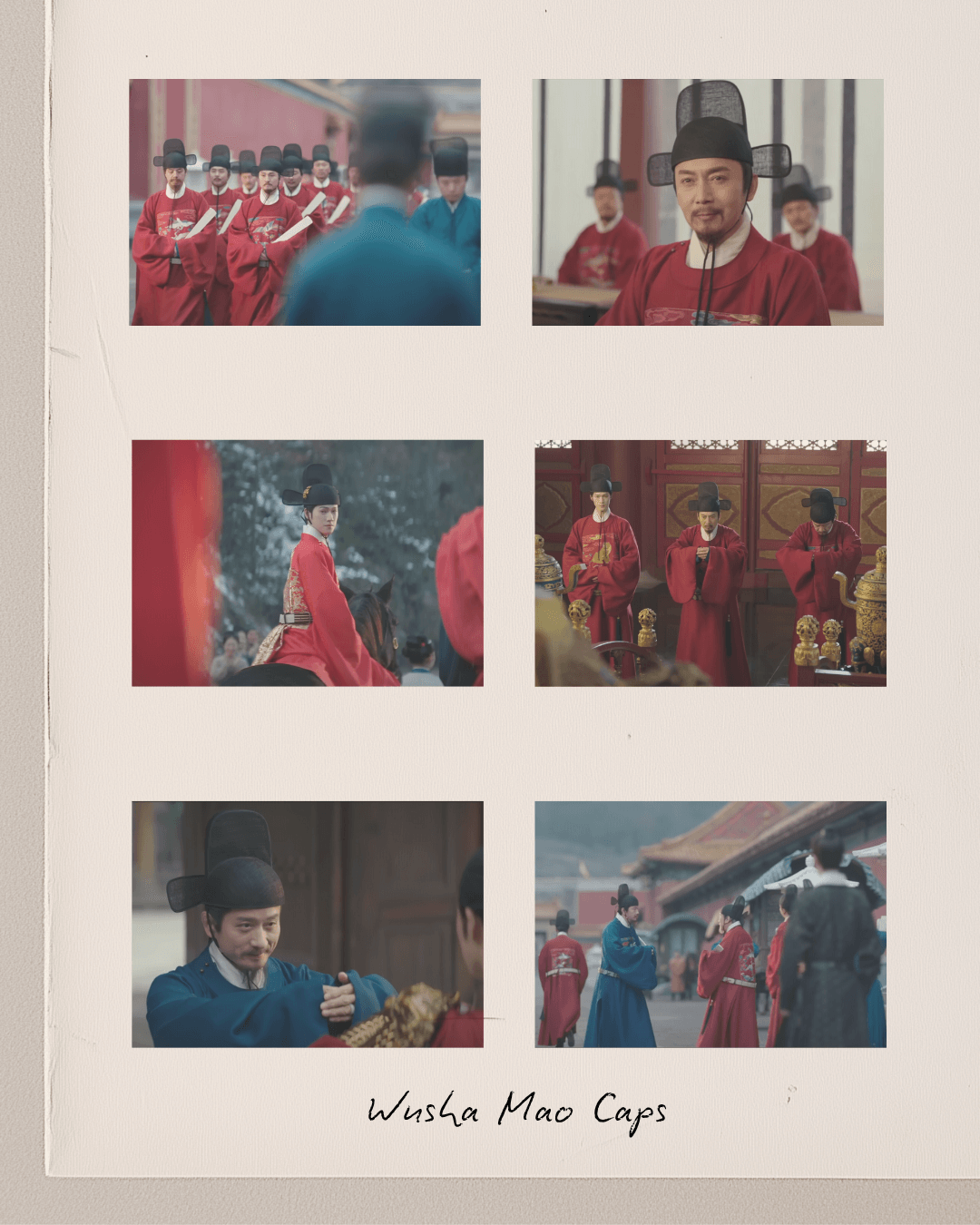

Wusha Mao: Officials’ Black Gauze Caps

The wusha mao (乌纱帽 wūshā mào) evolved from futou (幞头 fútóu) headwear worn by officials in the Tang and Song dynasties, particularly winged headwear known as zhanjiao futou (展脚幞头 zhǎnjiǎo fútóu) of the Song dynasty, ultimately becoming the defining symbol of government officials and officialdom during the Ming dynasty.

This black gauze cap features a rounded front, a raised rear section, and a pair of wings on both sides, reinforced with iron wires to maintain their shape. As its name suggests, the cap’s exterior was made of gauze and coated with black lacquer, providing both durability and allowing it to be put on and taken off smoothly. Compared to the zhanjiao futou, the Ming dynasty wusha mao had shorter and broader wings. Official rank could be visually distinguished by the width of the wings: the higher the rank, the narrower the wings.

The wusha mao was officially designated as the standard court headwear for Ming dynasty officials during the Hongwu reign. According to ‘History of Ming: Treatise on Attire and Carriages’ (《明史·舆服志》Míngshǐ · Yúfú Zhì): “in the third year of Hongwu, it was decreed that for all regular court sessions and administrative duties, officials were to wear a wusha mao, a round-collared robe, and a belt as their formal attire.”

Even today, the wusha mao remains synonymous with officialdom, as reflected in phrases such as “donning the wusha mao” (戴了乌纱帽 dàile wūshā mào), which signifies assuming an official position. On the flip side, “removing the wusha mao” (摘掉乌纱帽 zhāidiào wūshā mào) is a euphemism for dismissal from office.

Meanwhile, the emperor and princes wore a distinct variation of the wusha mao known as the yishan guan (翼善冠 yìshàn guān), meaning ‘winged crown of virtue.’ This was the most commonly worn headwear by Ming emperors during daily court sessions, both in the morning and afternoon.

Structurally similar to the wusha mao, the wings of the yishan guan are folded upwards rather than extending horizontally. This design carries symbolic meaning, with the two upward-facing wings resembling the two dots in the Chinese character for ‘virtue’ (善 shàn), and the front section resembling the character for ‘mouth’ (口 kǒu), which is also part of the character for ‘virtue.’ Together, these elements associated the yishan guan with virtue and moral authority.

For more Ming dynasty clothing and decor highlights, take a look at The Beauty of Ming Dynasty Style in ‘The Glory’.